Where the Path Leads-Chapter 7

The Visitor

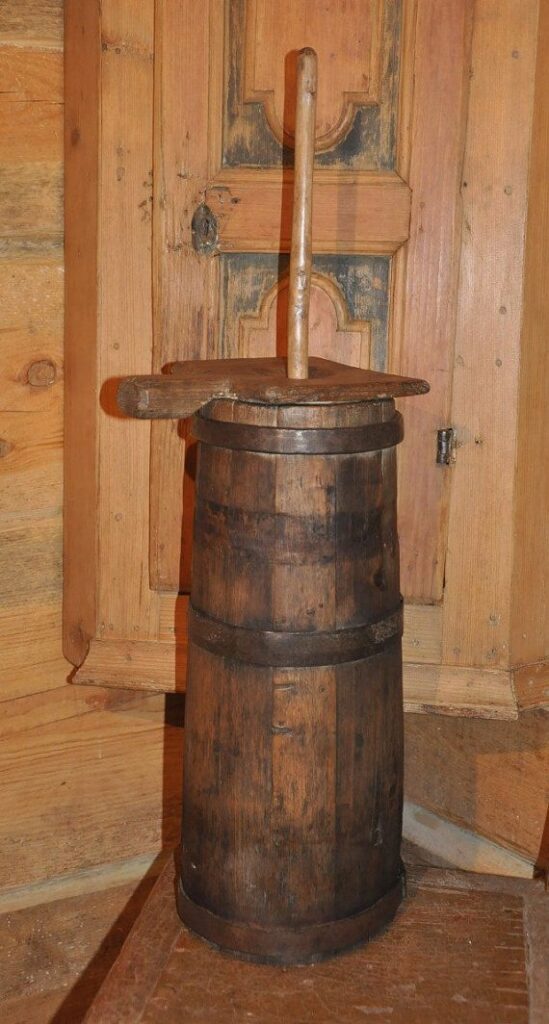

Emily sat in the doorway churning butter, sulky after a discouraging episode with the loom. The air was still. No cool breezes today.

Earlier, she had been trying to put hundreds of threads through tiny holes in the loom, a process called warping. Why did she have to do all this boring, tedious stuff first? She just wanted to get to the weaving. Then she’d gotten some of the threads crossed, had to take them out and go back to painstakingly rethread them. Finally, they’d gotten in such a tangle that she couldn’t get them undone, and she’d thrown down the mess in disgust and stood up.

“I can’t do this! It’s too hard. It didn’t look so hard when you did it.” She recognized them all as excuses, but her energy had waned along with her patience. Tired and hungry, she whined, “Isn’t it time for lunch yet?” She seemed hungry all the time lately, which made her grouchy.

Sophia had given her the butter to churn to calm her down, then sat down herself to untangle the knot.

“Can’t you throw them out and we’ll just start over? Chalk it up to

learning?”

“No, Emilia. We can’t waste. Besides, I haven’t any more homespun right now.”

Humph! Ugly stuff, anyway. Nothing like the green material. Weaving was such a long process, and whatever garment this became certainly wouldn’t be beautiful.

She beat the paddle over and over on the butter churn, mirroring her agitated thoughts. Was school this boring? Maybe her parents had sorted out their differences by now and they’d be so happy to have her back, they wouldn’t talk about separating any more. Things had been so easy when she was young, no responsibilities, easy homework, no boys confusing things. Without realizing it, she was attacking the cream in the churn. Sophia looked up, pausing in her untangling.

How long had the paddle been making that swishing sound, the cream having finally clabbered, and she still worrying it? When she lifted the lid, only frothy skim milk remained. Sticky yellow butter clung to the paddle and she scooped a big dollop onto her fingertip and stuck it in her mouth. It dissolved on her tongue, reminding her of the milk it had come from, but also the cheese it could have become. Somewhere in between. Even though it was so much work, it was worth it. While Emily savored the taste, a faint whistling came through the trees, more tuneful than birdsong.

They both looked towards the forest where a moment later the shoemaker’s son stepped out of the trees, hands in his pockets, his clear, mellifluous whistle carrying on the warm spring air.

Carefully setting the almost-detangled threads aside, Sophia stood up, walking out into the clearing.

“Greetings, Will. What brings you our way?”

He took off his hat, glancing shyly at Emily, who had gotten up as well.

“Good health to you, ma’am. It’s her that brought me out here, or her shoes, rather.”

For a terrible moment Emily was afraid he’d come to take them back, that he wanted to give them to some other relative of the Baroness, someone more deserving, more important. She could imagine having to take them off while he waited there, handing back the now slightly dirty, slightly scuffed shoes, her confidence shrinking back to its former undersized and puny self.

Perhaps Sophia also thought he was coming to get them back, because she hastened to say, “I’m weaving some homespun to give for them as well. I realize their worth.”

Emily frowned. Wasn’t the homespun hers?

“I’ll tell my father, ma’am. He’ll surely be grateful. But what brought me out this way is this,” and he held out a small clay pot. “Oil for her shoes,” and he glanced at her with friendly brown eyes. “It’ll keep the leather from drying out and cracking.”

“How kind, Will. Won’t you stay and sup with us?”

The mention of food makes her mouth water. This boy seemed nice, but did they really have enough food to share?

“I’m sure Emilia’s very grateful, Will.”

Recognizing her cue, Emily piped up. “Yes, thank you. It’ll be very helpful,” but remembering how concerned Will’s father had been about getting paid, she added, “But I don’t have any money to pay you. . .for the oil.”

An awkward silence ensued.

“I believe Will intended it as a gift, Emilia,” Sophia finally said.

Tongue tied, she looked with embarrassment at the soft, delicate shoes she’d worn this morning to milk Blossom, to clean the barnyard, to fetch water from the stream, in fact, to do all her chores. She wore them during all her waking hours and now they were dusty and mud splattered.

Following her gaze, he added, “You’ll probably want to clean them before oiling.” There was no blame in his voice, and his broad face was so guileless that she smiled. It was her first gift from a boy.

The three of them sat companionably in the warm sunshine of the dooryard eating brown bread spread with the butter she’d just churned. She tried to eat slowly, to savor it.

Despite Will’s easygoing, friendly manner, she wasn’t used to talking to boys, and only half listened while he and Sophia talked about gardens and how to keep out small creatures, like rabbits, squirrels and hedge pigs.

“My mother used to sprinkle a bit of dried blood in a shallow ditch around the borders,” Sophia was saying, “but that was when we could hunt. Now I use something that moves and makes noise, like branches, but the blood worked better.”

The warm sunshine, almost hot, made her drowsy, the bees humming around them, and a somnolent rustling of leaves in the treetops which sounded like gentle breathing. So, when Will spoke to her, she was unprepared for his question.

“Tell me something about the place where you’re from, Miss.”

Why was everyone here so concerned with where she came from? Was it because they so seldom had visitors? At school, when a new kid came in, everyone pretended not to notice her. It was uncool to say something like, Hi! Where are you from? All that mattered was your friends and what you were doing. You never even looked at the new person unless you had to pass her a handout in class or throw her the ball in gym.Even then, you just stared blankly, not acknowledging her. This frank curiosity made her uncomfortable. And did he really just call her Miss?

Once again, Sophia filled in Emily’s silence. “She’s come from a long way off, Will, but her appearance here was lucky for me. I needed help and there she was, at my door.”

“Just like a miracle,” he said.

Emily felt her face color.

But he wasn’t to be put off. “My whole life has been spent here in Ephemera, and my parents’ lives, too. I would love to hear about faraway land and different places. Do you live in the mountains? Or near the sea?”

Sophia stood up and going a little way out into the yard brushed the crumbs off her dress onto the bare ground for the chickens. “Perhaps you two can hunt mushrooms while you talk. I’ve got a craving for some in the pottage. Mind you Will, she’s already gotten lost once, so keep an eye on her. And she has no idea which mushrooms are good to eat, and which will sicken you, so you can show her.”

Will grinned.

She couldn’t believe Sophia was sending her off with him. He was nice enough, but she had no wish to be pestered with questions from some bored village boy. When she began to protest, Sophia waved away her excuses and handed her a basket woven from grapevines. “There’s nothing that can’t wait. Just don’t be gone too long.”

“We won’t ma’am,” said Will. “I have verbos Anglais to memorize that Tado Lawrence gave me and chores at home,” but he headed towards the woods. She reluctantly trailed after him. When they came to the stream where she went to collect water each day, he offered her his hand to help her across. Confused and embarrassed, she shook her head, then slipped on a mossy rock and got part of her shoe wet.

“I’m good at finding mushrooms,” he announced. “I know where to look for them, in moist, shady areas, out of the way.” He crouched down and dug around in some dead leaves bringing up one triumphantly. “See how they’re brown on top, then darker brown underneath?” He turned it over for her to see the ruffled underside. “Now if they’re black underneath,” he made a face.

“Do you want to tell me about where you’re from?” He sounded hopeful but was looking down at the ground for mushrooms and moving slowly through the woods.

“No.”

“Why?”

“Because you wouldn’t believe me if I told you.”

He looked up. “Is it that fantastical?”

“No. Well, yes. Well. . . much different from here, very different.”

“People in the village say you’ve been sent for a reason.”

“Why? What do they think I’m here for?”

“Nobody knows. Not a lot of people visit here, as you might’ve guessed, and you’re not like anyone that’s ever been here. Because folks are unhappy with the way things are, some think you’re a portent of change.”

“What do you mean?”

“Well, folks want to be more like you and have the opportunity to move around, do what they want.”

“You think that’s how I am?”

“Well, you came here, didn’t you? From a long way off, according to Sophia.”

“Look, I’m only here by. . .by accident.”

He tilted his head, giving her a confused look.

“I got lost. Or I wouldn’t be here.”

Spying another mushroom growing between the roots of a tree, he picked it and put it in the basket.

“Then you didn’t choose to come here?”

She shook her head, then decided to change the subject.

“You’ve known Sophia for long time. Tell me about her.”

“Me? She’s your aunt.”

“Well, I haven’t been around her that much.” She didn’t want to admit the ruse.

“Generally, everyone respects her, though she’s a loner, as you know. People always wonder about them.” Lowering his voice, he added, “I’ve heard it said she’s a witan.”

Now Emily looked puzzled. “A what?”

“We’re not supposed to speak it,” he stood close to her, almost whispering. “A wise one. In the old lore, the ancient wisdom of rocks, birds, and trees, in the days before soldiers and priests. Papa says it’s dying out. Someday it’ll be gone forever.”

“Why do they call her that?”

“Emilia, you live with her. Haven’t you noticed?”

She had observed that Sophia knew a lot about domestic things, like mixing manure and leaves to make fertilizer for her garden, which seemed to yield abundantly. Or how to tell what an animal was thinking, like when Blossom switched her tail, it meant she disliked something, or when a lot of white was showing in the cow’s eyes, then she was afraid. An everyday kind of wisdom.

“Yes. She knows a lot about plants and animals.”

“And other things. Some say her powers go beyond nature, that she can see into the heart of things.”

They were standing close, whispering, in the shadows of the trees. She drew back, suddenly self-conscious.

He spotted another mushroom, again showing her the underside before putting it in her basket.

They continued walking.

“Last Whitsuntide,” he confided, “we were getting ready to celebrate. You know–the Morris dancing, feasting, wrestling matches. Everyone was so gay, what with summer before us and a week off from working in the Baron’s fields. But as Sophia left church that day, she said she must head home and take apart her oven.

“Now it was a lovely, sunny day, with no wind and high puffy clouds. So why would she do this? Stay, have a cup of Whitsun ale, we said. Watch the maids dance in their white dresses. But she would hear none of it. Said there were some as never took a holiday from scheming, and the powers of the castle would deprive us of our daily bread.

“We didn’t know what she was talking about and some laughed and called her daft, so intent were we all on celebrating. But before high sun, the Bailiff rode into our midst and announced that henceforth all bread must be baked in the castle ovens, at the mill. The miller already cheats us out of part of the wheat we take for grinding, now we must pay him to bake the bread as well. Anyone found with his own oven would be fined, said the Bailiff.

Will still shook his head in disbelief. “How did she know? Some say espiritu mundo is in her–the world spirit,” he explained, seeing her confusion. “Others, that she reaches inside your head to decipher your thoughts. Whether it’s in her or whether she taps into what is outside her, one thing is for sure. Sophia’s got more wisdom than most. Can you not tell?”

From their very first meeting Emily had been impressed by the depth and intensity of Sophia’s gaze, as if the older woman could read her deepest thoughts and desires. She had noticed how, when Sophia sat at her loom, like when she had made the green-gold cloth, her eyes had a faraway look as though seeing things that were not in front of her.

“She thinks a great deal of you,” Will added.

Emily smiled. “How do you know? She’s never said anything.”

“I can just tell.”

A rush of gratitude made her suddenly feel that she could trust him. “Will, do you know how to get to the castle?” Ever since first seeing it, she had longed to get up close. Even though Sophia had cautioned her, surely it would be safe with Will as her guide. And it was still early enough, she thought, to get home before supper.

He laughed. “Of course. Have you been there?”

“No. I saw it from a distance the day I got lost.” And she told him about trying to get the cow out of the cornfield and seeing the castle.

He let out a long, low whistle. “You’re lucky nobody saw Blossom in that field. They might get plenty mad at her eating the Baron’s corn.”

“She didn’t eat that much,” Emily countered, then admitted, “Someone did see her. A man on a black horse.”

His eyes widened. “Did he have yellow hair and a hat with long feathers?”

She nodded.

“Did you tell Sophia?”

She shook her head.

He groaned. “Oh, this is bad.”

“Why? Who is he? He was terribly rude.”

“Rude? That’s Simon Poyntz, the Bailiff, who enforces the Baron’s laws. Baron Longsword is the one who owns the castle, the village, this wood, Blackwood forest. . .everything.” He opened both arms in a broad sweeping gesture as if indicating the entire world, which is what it must have seemed like to him.

“It was just a cow, who strayed there accidentally.” She frowned. “What’s the big deal?”

“Big deal?” he said, repeating the unfamiliar phrase and putting his hand to his forehead. “Well, that’s food for the castle, and there are many who would look darkly on it being consumed by a creature.”

“Will, please don’t tell Sophia,” she pleaded, “and don’t tell her this, but I want to see the castle up close, as long as we don’t run into the Bailiff.”

He considered for a long moment.

“Please,” she cajoled. “It would mean so much to me.”

He shook his head again. “For someone who’s new here, you sure seem ready to stir up the pot,” but as he quietly clasped her hand and began leading them in another direction, neither had any idea how prophetic his words would turn out to be.

Emily tried to note the way they were going, but nothing looked familiar. Finally, she recognized the hedgerow of brambles whose leaves were now in full bloom, but this time they walked around a swampy area and up a much less steep hill than she had scaled last time. At the top of this small hill was a narrow path partially obscured with weeds that had been brought to life by the recent warm weather. She followed him a short distance to the wood’s edge, which bordered a cornfield, and was rewarded by seeing, once again, the castle, resplendent in the afternoon sun. Now, as before, it filled her with awe and admiration. On impulse she squeezed his hand and said, “C’mon. Let’s get up close.”

He shook his head. “We have no errand there.”

“That’s OK. I just want to look. See some of the people.”

“You’re a bold one,” he laughed.

Uncertain whether or not that was a compliment, her face flushed.

“I don’t have to meet anyone. I just want to look around.”

“How do you plan to do that? Peer through the cracks in the wall? They’re three feet thick. Besides, the Bailiff is often there, and it sounds like you’ve already angered him.”

But thoughts of the Bailiff didn’t affect her desire. As far back as she could remember, castles had enchanted her. From the first time her father read her Cinderella,to her own recent reading of The Demi King, it was where all the action took place. The Renaissance Faire had been a pale imitation. This was the real thing, with a moat and drawbridge, a portcullis, crenellations, parapets and spires. She had to touch it, even go inside. Filled with excitement, a distant movement on the road caught her eye. People trudging towards the castle.

“Look! They’re heading toward it.”

Will shielded his eyes against the sun. “Laborers, returning from work,” he said.

“Let’s join them. Walk up with them. Then it won’t be just the two of us. Please, Will. I just want a closer look.” Her coaxing tone must have worked, because his voice softened.

“Well . . ..”

She smiled, jerked her head in the direction of the laborers, and took off at a light run through the rows of corn. She hiked up her tunic to run, and excitement made her feet seem to skim over the ground. She had never been much good at running, usually got a stitch in her side and was out of breath in no time, and she wondered if it was the shoes that had given her more energy, and confidence that she could go the distance. The castle was at least a mile and a half away. By the time they reached the laborers, they were both flushed and breathless, but she was exultant. The dust-covered family, a weary looking man, woman and young boy, stared at them open-mouthed, hoes still in their hands.

Their stares made her suddenly self-conscious, and she was grateful when Will spoke.

“Greetings. We’re going to the castle as well.”

They fell into step alongside the laborers. For a while, there was silence among them. The family had stared at them so blankly that Emily wondered if they spoke another language and hadn’t understood. Suddenly, however, the man inquired, “What business ‘ave ye?”

“No business, really,” she piped up. Will glared at her. “Well, uh, we have someone to see,” she said, correcting herself. It wasn’t really a lie. She did want to see someone, everyone in fact who lived there.

“Well, if it’s work ye seek, ye’ll not find any,” said the man, his voice cracking and his stride slow, as if every step was a measured expense of his limited energy. The woman and boy trailed silently behind.

“No, we’re not seeking work,” Will answered amiably.

The man eyed them suspiciously. “The only visitors welcomed these days are royal ones.”

“We’re not planning to stay,” Will assured him.

Perhaps she should have listened to Will after all, when he said they needed a reason to go there.

No one spoke the rest of the way. Once, Emily caught the woman looking furtively at her, especially her shoes. She smiled at her, but the woman quickly looked away, staring at the ground. Strange, how so many people here didn’t want to look you in the eye, she thought. Except for Sophia.

Nearing the castle, she caught her breath, her heart pounding in response to its size and strength. Stopping in the road she stared up at the crenellated outside walls surrounding the towering keep within, both built of massive grey rock and backlit by the golden splendor of the late afternoon sun. Will caught her elbow just as she spotted movement near the top of one of the outside walls. “Come along,” he urged, looking up too. “We’re being observed.”