Fantastic Flora – Sedges

Hidden In Plain Sight – True Sedges, Genus Carex, Sedge Family (Cyperaceae)

- SALLY L. WHITE –

If it seems the world is full of grasses, that is not far from truth, but some of those long green leaves we encounter are not grasses at all, but sedges. With some 5,500 species worldwide, more than 2,000 members of this family are “true sedges,” belonging to the genus Carex. (A genus is a collection of related species.)

“Sedges have edges,” students are taught in college botany courses, but I recently learned the sequel of that little memory cue, which helps us distinguish further: “Sedges have edges, rushes are round, grasses have nodes right down to the ground.” That’s a simplification, but you can often roll a stem between your fingers to assess its shape. You’ll find grasses are round or possibly flattened a bit, but never “edgy.” True sedges are triangular in cross-section, a quick and helpful test. (Let’s leave rushes out of it for now.)

In New York, we reportedly have about 215 species of true sedges (including hybrids), or roughly ten percent of the world’s total. Ninety percent of them are native, but a third of those are uncommon to rare. I don’t expect to sort out more than a few of the obvious ones, but at least I can often tell they’re sedges; perhaps that’s enough. (Anything more would require patience, and a microscope.)

Most true sedges, genus Carex, have a distinctive appearance, a “look” to their texture and color that helps us pick them out in the landscape. In this photo, yellow-green sedges in the left foreground mingle with rushes.

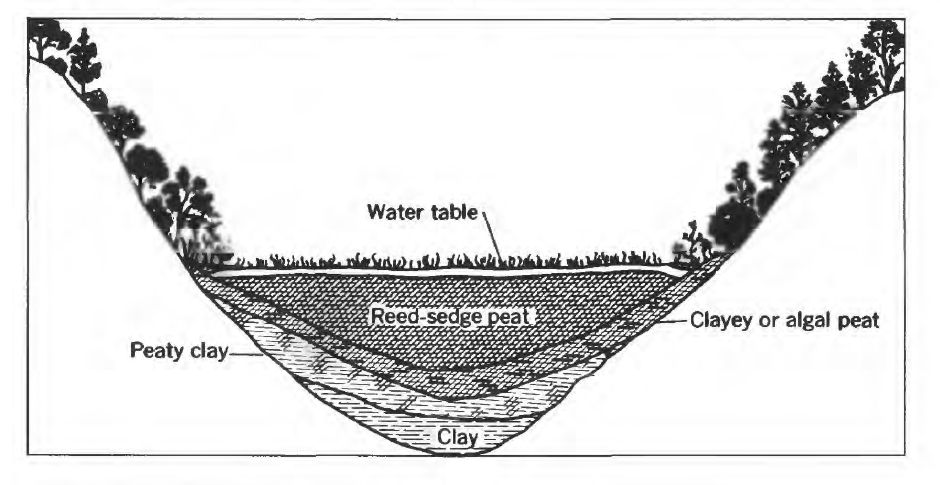

We can be excused, I trust, for thinking of sedges as wetland plants. That’s where we’re most likely to see them and where they occur in expansive communities, sometimes with rushes and reeds. Waving gracefully at the edges of ponds or filling in marshes and fens, these grass-like plants become the visual matrix for more ostentatious flowering plants, the ones we tend to notice. Wetlands dominated by sedges are often called fens and have played a significant role in New York landscapes. In our area, sediments deposited in glacial valleys created habitat for sedges and other wetland plants.

Most Finger Lakes are in valleys deep enough to persist as lakes, but smaller ones become wetlands in time. Changes in the water table create long cycles of sedges and other wetland plants, growing then being killed by floods, slowly accumulating the layers and layers of organic matter we call peat, or muck. As much as 80% organic, that “muck” is a great carbon sink in these days of climate concerns. In southeastern New York, reed-sedge peat 15 feet deep has accumulated at a rate of one foot every 1,500 years; ours may not be as deep, though thousands of years old.

A century ago, Potter Swamp (Yates and Ontario counties) was a forested wetland attracting many species of birds. Beginning in 1894, Verdi Burtch and Clarence Stone began making regular visits to assess its wildlife, especially the Great Blue Herons who nested in a rookery there. By 1930, they talked of making it a bird sanctuary; others spoke of a wildlife refuge. Even today the distinction between a “refuge” and a “sanctuary” is not evident from the names. “If the state wants a place to raise and then shoot ducks,” said Mr. Burtch, “I would just as soon they do it someplace else.”

By 1932, Dr. Eaton of Hobart was making annual trips to Potter Swamp, with bird lovers from Geneva, Rochester, Buffalo, and Syracuse. His May 1932 visit attracted 200 people, who together reported 166 species of birds. Mr. Burtch’s idea had enough momentum to generate protests. A letter to the editor of the Chronicle-Express thought the land better suited for “muck gardening.”

Charles Oswald wrote:

“The Potter swamp is possibly one of the finest pieces of undeveloped agricultural land in the eastern states…. We would consider it a great mistake to have it tied up by the federal government for any kind of conservation purposes.” Such arguments prevailed, for Potter Swamp became some of the most productive agricultural land in the region. Unfortunately, its story was repeated in other mucklands.

The promoters of “Save Bergen Swamp” were more successful, beginning in 1935 when garden clubs helped create the Bergen Swamp Preservation Society. The Society is still active, and in time 2,000 acres of the Bergen-Byron Swamp in Genesee County were designated as the nation’s first National Natural Landmark in 1964. More than 10,000 acres west of Bergen Swamp was designated the Iroquois National Wildlife Refuge in 1958, but much of the “Great Tonawanda Swamp” (glacial Lake Tonawanda of 11,000 years ago) had been converted to muckland farming. A complex of state wildlife management areas adds another 8,000 acres of protected area, most of it wetlands, between Buffalo and Rochester.

I was fascinated by Potter Swamp (in Yates and Ontario counties) when I heard about it, and now I’ve concluded it is our twelfth Finger Lake, hiding in plain sight. When filled with water, “Potter Lake” would have been twice the size of modern-day Honeoye Lake. Like the ghostly arm of Y-shaped Canandaigua Lake, 15,000 or 20,000 years ago it probably held a shallow basin of open water, collecting sediments from Flint Creek. Eventually reeds and sedges (and when the water level lowered, trees) would have filled the valley we know today as Potter Swamp, a “muckland” that’s not been a swamp since it was drained more than 50 years ago.

Everyone who enjoys observing nature can be grateful that other “swamps” in Western New York escaped that fate. Across our region, we can still observe wetlands at the southern end of most “fingers,” Honeoye Inlet Wildlife Management Area and Queen Catherine Marsh being nice examples. We have Montezuma National Wildlife Refuge, a stopover for migrating birds, at the north end of Cayuga Lake—all great places to look for sedges and other wetland plants. Chances are, though, you can find fascinating sedges in your backyard, or as close as the next lake or pond. Don’t forget—check for edges when looking for sedges!