Fantastic Flora

Patience Pays Off For These Late Blooming Grasses

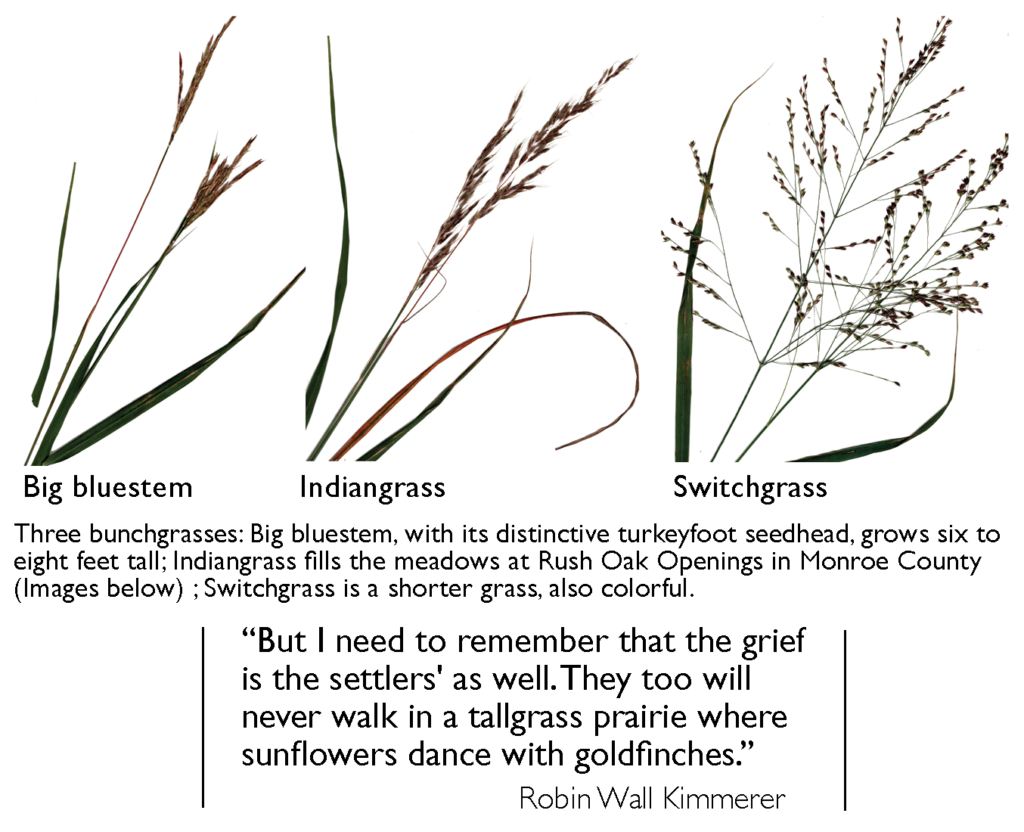

– Big Bluestem, Andropogon gerardii; Yellow Indiangrass, Sorghastrum nutans; and Switchgrass, Panicum virgatum— the Grass Family, Poaceae

- SALLY L. WHITE –

As I learned about and lived with grasses over many years, I developed several serious prejudices. All plants are interesting, of course! But some have earned my deep distrust and even hatred. Others, I’m happy to say, have my sincere admiration. The three species above are my favorite grasses. They once dominated vast areas of tallgrass prairie in the central part of this country.

The grass family is among the largest families of flowering plants. With 12,000 species, and about 400 right here in New York, grasses encompass incredible variety. Beyond introduced species like corn and wheat and the invasive reed grass (Phragmites) that’s taking over along roadsides and in wet areas, we can also find about 200 native species here. Some, if I see them, will be old friends, but many will be new.

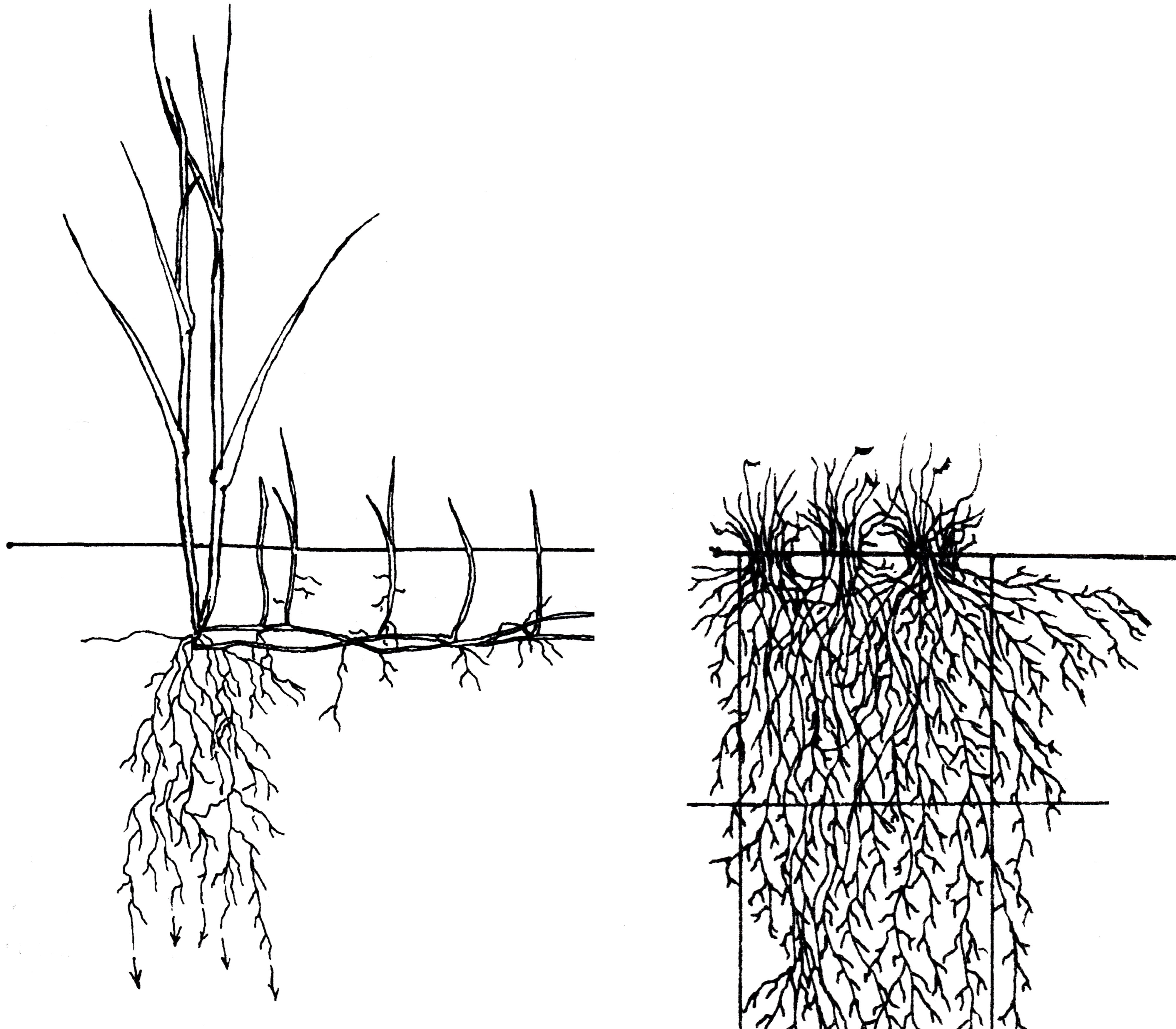

S. L. White, after J.E. Weaver. Not to scale.

Kentucky bluegrass is familiar to most, valued for its service in lawns. A cool-season grass that takes advantage of early season moisture to start growth, it’s also a sod-former. It spreads via underground stems, a handy habit that enables it to be planted in sheets and fill your entire lawn. Without mowing, it flowers about May and sets seeds by July. Nice and normal, maybe even well behaved.

Some grasses choose another strategy: patience. Only in the height of summer do the grasses we call “warm-season grasses” start to come into their own. Most are bunchgrasses that, in contrast to sod-formers, form clumps that grow slowly in size rather than expanding laterally across the landscape.

These three bunchgrasses are among the most beautiful grasses in our landscapes. They are native here, as they are in the tallgrass prairies of the Midwest, though less abundant. There they can cover substantial areas and grow tall enough to hide the herds of American buffalo (okay, bison) that used to share their habitat. Now, along with the buffalo, they occur only in a few preserves and protected spots plows didn’t reach. Prairie has not been a favored ecosystem in American history; some report that only about one percent of an original 240 million acres remains. Most has been converted to corn, wheat, and other agriculture, as a drive across Iowa and Kansas will reveal.

Beyond their intrinsic values, native species offer a variety of what we call “ecosystem services.” Gardening for wildlife? Their robust size makes them good nesting and escape cover for small mammals and birds, which also readily consume the seed; deer use them for forage. Want pollinators? Native tallgrass species serve as larval hosts for butterflies, especially several kinds of skippers. Towering structure and graceful swaying stems add diversity and texture to the landscape and physical support for native wildflowers in these plant communities.

For humans, we can point to the economic roles these three species have. They are used along roadsides for erosion control and provide good forage for livestock as well as deer and bison. Nurseries and landscapers have discovered their value even in formal plantings. Tallgrasses are essential for prairie restoration projects, as we try to recover what we once tried to eliminate.

By late July, clumps of big bluestem send up flowering shoots six or eight feet tall that produce distinctive “turkey-foot” seedheads in August. After cool-season grasses are giving it up and seed has scattered, big bluestem ripens into terra cotta masses that reveal its presence even from a distance. The Indiangrass we saw in Monroe County, equally tall, had turned golden bronze with autumn and was highlighted by the rosy copper of little bluestem with its sparkling silver fluff. What a treat to walk among grasses that towered overhead!

All three of these tallgrasses are attractive accents in gardens, but their size dictates giving them adequate space. They can replace exotic ornamentals like Chinese silvergrass and fountain grass and are beginning to be more widely used. Here, prairie switchgrass dominates landscaping at the Geneva Lakefront near the Ramada Inn.

While working on this article, I finally realized why I haven’t thought much about grasses here in New York. In Colorado, grasses dominate in many habitats; here they are often thrust into the background as trees become the focus of attention. To visit one of these remnant prairies (or here in New York, oak savannas) is like traveling two centuries back in time; it will change our perspective and perhaps give us new appreciation for tallgrasses and their rare ecosystem.

2 thoughts on “Fantastic Flora”

Comments are closed.

Sally is Indian grass different from Sweetgrass or are they interchangeably used words?

Robin Wall Kimmerer is where I first learned of the term sweetgrass and obtained a start from a Ganondagan and Shimmering Lights Farms combined offering this past August.

Thanks for the question, Carol. They are indeed different plants. Indiangrass is genus Sorghastrum, and Sweetgrass is genus Hierochloe.

Hierochloe odorata is a northern species and occurs across Canada and down into our region. Lucky you to have some!