ASTRONOMY: Magnitudes More Fascinating Than You Imagined

- DEE SHARPLES –

| Magnitude measures the apparent brightness of a celestial object and is expressed by a decimal. An object with a negative number like our Sun is brighter. Sun: magnitude -26.7 Polaris, the North Star: magnitude 2.0 |

Being interested in all things astronomy began the summer I was 11 years old and discovered the science fiction shelves in the tiny branch library located in my city neighborhood. My fascination continued, ebbing and flowing with my age and what new discoveries and achievements were being made by the United States space program. It reignited when the first U.S. manned space flight blasted off in 1961 and became cemented firmly in my being when I witnessed the awe-inspiring moment when Neil Armstrong became the first human to step onto the surface of the Moon.

As an adult, daily life and responsibilities didn’t leave me much spare time for developing my fascination with the universe. I read books by authors like Carl Sagan, who focused on educating the general public. “Sagan was perhaps the world’s greatest popularizer of science, reaching millions of people through newspapers, magazines, and television broadcasts”, as stated in his obituary published in the Cornell Chronicle on December 20, 1996. Neil deGrasse Tyson, director of New York City’s Hayden Planetarium, currently writes books and hosts television programs appropriate for anyone fascinated by our amazing universe.

After becoming a member of the local astronomy club, the Astronomy Section of the Rochester Academy of Science (ASRAS), I discovered there were many ways I could explore astronomy, both as a hobby and making actual contributions to science.

My excitement just to be part of a group of like-minded astronomy enthusiasts blossomed immediately as I joined other members on observing nights at the Marian and Max Farash Center for Observational Astronomy, the ASRAS dark sky observing site in Ionia. I had my first opportunity to look through various telescopes, some smaller 4” to 8” easily transportable ones belonging to members and a huge club-owned telescope, so big we had to climb a 6’ rolling step ladder to reach the eyepiece.

I was definitely hooked and had to have my own telescope. After checking out the various types, models, and sizes of telescopes owned by other members and comparing the pros, cons, and prices of each,

I made my decision to buy a Meade 8” Schmidt-Cassegrain. It was fairly heavy, but I was still able to carry and set it up in my backyard or at the observing site. It was capable of ample magnification, was motorized for tracking the stars as the Earth rotated, and able to accommodate a piggy-back camera and direct-through-the-eyepiece photography. At Ionia, I connected with two ASRAS members who had similar scopes and they became my mentors, teaching me how to set up, align, and use my telescope. They also showed me how to read a star chart, what easy-to-locate targets were best for beginners, such as planets, star clusters, and the brighter galaxies.

My enthusiasm fueled my capability to carry my heavy telescope outside to my backyard to observe every chance I had. Neighbors’ house lights could be frustrating at times as I scouted for the best location in the yard to avoid them. I was also a little skittish about some nocturnal animal, like a skunk or a raccoon, surprising me.

That’s when my husband built me a simple roll-off observatory which made a world of difference in my comfort level while enjoying the night sky. The height of the walls blocked any neighborhood light pollution allowing for more frequent and convenient observing sessions as my telescope now had a permanent home out there.

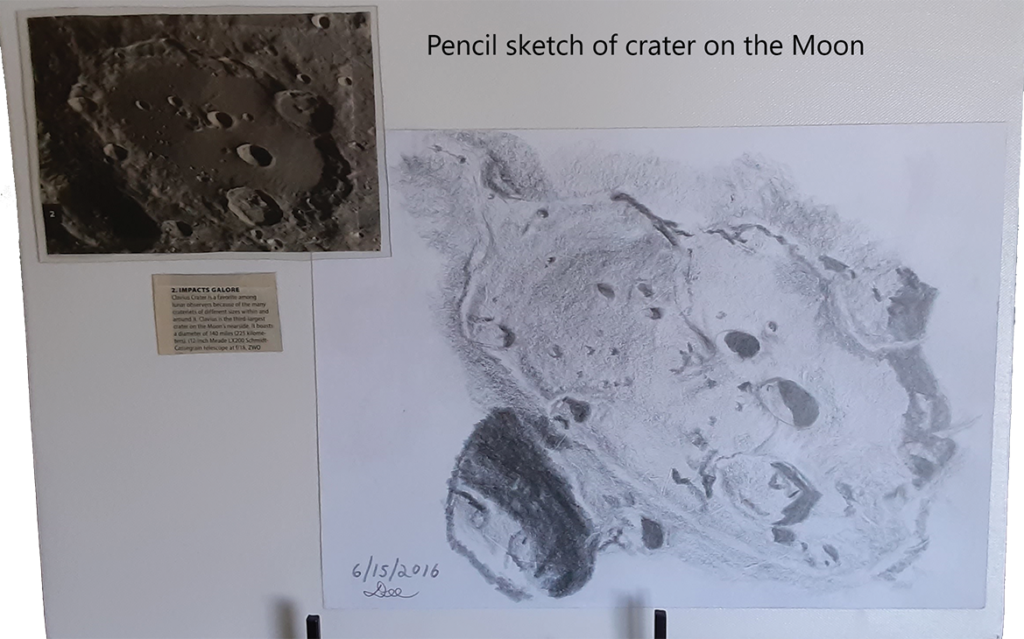

Astrophotography now entered the realm of possibilities. By mounting a 35mm camera on the optical tube of my telescope (piggy-back), I could now automatically track the movement of the stars for long exposure shots to capture fainter objects invisible to the naked eye. I was also able to take close-up pictures of the moon—like the one featured here—by focusing the camera through the eyepiece.

The unusually perfect warm, clear weather for the peak of the Leonid meteor shower on November 18, 2001, allowed me to randomly snap pictures with my camera of the still dark, very early morning sky, and I was delighted to see how many meteors I had captured streaking across the sky.

On the night of October 30, 2003, as we were driving home, we noticed the sky looked strangely unusual. That was when I witnessed my first-ever observation of a rare colorful display of an Aurora Borealis. I hurried to mount my camera on a tripod and took photos as the sky to the north changed colors in waves of green and pink. It seemed that the night sky was offering me a rare gift.

I wanted to contribute to the science of astronomy in some way and was introduced to the American Association of Variable Star Observers (AAVSO) by another astronomy club member. By observing stars designated as “variable stars” because their magnitude brightened and dimmed on a periodic basis, I learned how to compare them to nearby stars that glittered at a stable, known magnitude. This organization encouraged amateur star gazers like me to submit their data which was entered into a database. The data is used by professional and amateur astronomers as well as students doing research on variable stars.

AAVSO also had a section dedicated to observing sunspots. I purchased a solar filter and counted the number of sunspots I could see on each clear day, reporting that number to the organization for research purposes.

Observing a star field through my telescope on a warm summer evening is therapeutically relaxing for me. I found that sketching what I saw through the eyepiece slowed down my experience and enhanced the feeling of peace that always washes over me when I look up at the stars.

I registered to take a pencil sketching class and was invited to pick any subject. I brought in a photograph from a magazine of a crater on the Moon, and over the next six weeks, I learned how to duplicate the shapes, tones, shadows, and topography of the crater. I’ve also sketched Moon craters as I was observing them through my eyepiece. This takes about 45 minutes to frame out and then I enhance the shadows and tones after I close down my observing session for the night.

Sharing astronomy experiences with family and friends has always been a highlight of my observing. When I locate an especially pretty nebula or star cluster, I’ll rouse my family out of the house to come and take a look. It feels like I’ve found a treasure and I want to share it with others.

Most recently I enjoyed the annular solar eclipse from the comfort of my backyard. It sometimes is hard to set an alarm to wake you at 5:15 AM, but I find it’s always worth it.

This month, the peak of the Perseid meteor shower is in the early morning hours of August 12 and 13. You should be able to see about one meteor per minute under a very dark, clear sky away from city lights. Look northeast about halfway up from the horizon around 4:00 A.M. on either morning. I still chuckle when I remember the year my 14-year-old son and I relaxed in lawn chairs watching the sky to spot a Perseid meteor. It wasn’t long before the still morning air was punctuated by the sound of heavy breathing as my son dozed off under the stars.

Sharing my life-long love for astronomy is definitely a magnitude -26.7 experience for me, a personal joy, just as dazzling as our Sun!