Where the Path Leads-Chapter 15

- MARY DRAKE –

The Consequences

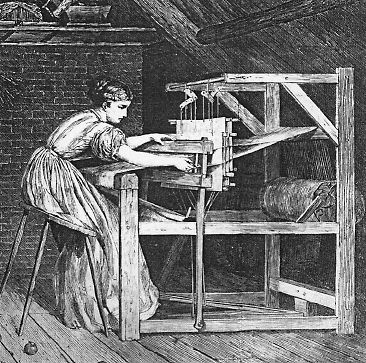

Sophia had been sitting at the loom all day warping the loom prior to weaving more cloth for the Baroness. This time it was to be a deep burgundy; perhaps the cloth would be made into an autumn gown for Rosamond’s wedding, but the threads were damp in her hands and stuck to her fingers. Right now, the wedding seemed a long way off. Sophia was more concerned with Emilia and how the poor girl must be suffering in this heat. Thinking of the sun beating down, she wove in some cool blue threads; thinking of the rich muck in the water meadow, some green for the plants; thinking of Emilia’s sweet nature, hints of gold. Overall, it would be burgundy, but no fabric had interest unless it had undercurrents of other colors.

It was the horn that made her pause as she threaded the myriad heddles. The nobles were out hunting, and she bowed her head sadly for the animals, even while sweat trickled down her back.

Later, when she had begun weaving and was throwing the shuttle back and forth, over and over, to create the fabric’s weft, she found herself mesmerized as the cloth materialized before her, its colors blurring into a feeling image, a thinking/seeing power she had developed as a young girl, and which she now allowed to carry her farther afield into the present. She was overcome by the oppressive heat, by a sense of utter fatigue that made her dizzy and made her head ache. Suddenly enervated, as if all her strength had drained out her fingertips, Sophia feared for Emilia. It was too hot and she needed rest, but the laborers were forced to continue. Something was going to happen and her hand trembled as she released the shuttle to travel from one side of the loom to the other, her heart pounding and her breathing going faster and shallower.

Concentrate, Sophia, concentrate. How is Emilia? Where is she?

Struggling to pay attention, her seeing thoughts morphed into a clearer image of a green place. The forest? But . . . why was Emilia there? Why was she afraid, running? Thudding hoofbeats sounded in her ears, as if someone would gallop right into her.

Sophia gasped, dropping the shuttle, her heart still pounding. She was right to worry about the girl, but then the hoofbeats in her vision sounded right outside in her yard. Had the image become reality? Taking a deep breath, she bent to retrieve the fallen shuttle and carefully tied off her last thread.

Late afternoon sunlight slanted in through the doorway, illuminating the black horse and its rider in the clearing.

She looked around the humble cottage with its dirt floor and earthy smell of simmering vegetables, the loom which took up so much space and now held the rich burgundy fabric that washed the cottage in color like a fiery sunset, and the straw bed in the corner with Emilia’s calfskin shoes beside it. She rose and damped the fire, wondering where it all was leading.

Summoned by the Seneschal, she followed on foot behind the Bailiff’s horse. He didn’t tell her anything, so she had plenty of time on the five-mile walk to the Seneschal’s manor house to consider what had happened. On some level she had known from the moment the girl stepped across her threshold that she would change everything. Now she was about find out what that meant.

Brutus Morantur’s manor house had a large stone fireplace and he was pacing in front of it, still wearing his scarlet tunic from the hunt, twigs and bits of leaves clinging to it and his leggings, strands of dark hair damp with sweat stuck to his face.

A laborer from the village named Adcock, covered in mud, stood in the middle of the room, hat in his hands. When Sophia came in, he looked up at her, then at the Seneschal. They waited as a serving boy poured the Seneschal a glass of wine, which he downed before speaking. When he did, he exploded.

“Do you know what you’ve done, madam?”

“No sir,” she answered calmly, but her heart was pounding.

Brutus glared at her, then with an exasperated sigh sank into the massive oak chair by the fireplace and motioned the boy to pour more wine.

“Just coming back from the hunt and I must deal with this. Your niece has left her work at the meadow and before leaving stirred up unrest among the laborers.” Gesturing to Adcock, he said, “Repeat what you heard.”

“I heard her ask ‘em why they had to give part of what they grew to the lords, since the land they lived on should by rights be theirs, seein’ as they live on it. She called it somethin’ like ‘squatter’s rights.’ Said that where she come from, they choose who they wants to be lords. I saw her when she left, told her as she weren’t allowed in the forest an’ called her back, but she weren’t for listening, just kept walkin.’ Had to see the dragon finches. I tried callin’ her back,” he repeated, looking from the Seneschal to the Bailiff and back again, for approval.

The Seneschal stood back up to face her, flushed with anger. “Who is this mere girl that dares question the Baron’s claim to the land, given him by the King? Dares question the rightful order of society? This is treason.”

“My lord,” said Simon, “the girl doesn’t even recognize the authority of the Absolute. She was irreverent when Monseigneur St. George led us in homage at the feast, didn’t lower her head or chant the oracion. She said that following the ritual was a personal decision.”

“Ah, heathen as well as anarchist,” Brutus exclaimed, pacing again. “What say you, madam?”

Sophia chose her words carefully. “Your lordship, it’s only that she sees the hard lot of the laborers. And it’s different where she comes from.”

“And where, pray tell, is that?” He approached Sophia.

The great room where they stood was silent except for the crackling fire. Sophia shifted her weight from one foot to the other, sweat prickling around her hairline.

“She’s your niece, is she not? Or so you have told everyone. I want to know, where is this place they choose their own lords?”

Sophia shook her head, unable to admit that she didn’t know, that she had never asked. Her concern had always been with this world and with the girl herself, not her past. She couldn’t explain what had happened, or even why Emilia had appeared on her doorstep in the first place.

Brutus sat down again, as if tired of waiting for an answer.

“We’ll find this troublemaking girl and get to the bottom of it.” Wearily he ran his hand through his dark hair, his anger seeming to abate. But he wasn’t quite finished. “Until we do, Simon, deliver Mistress Weaver to Morwen and tell him to install her on the third floor. At least she won’t be going anywhere.”

“But your lordship,” Sophia objected, “I have work back at my cottage–a dress for the Baroness, a cow to milk, and the girl might return there.” Sophia hated the pleading tone in her voice.

He laid his head back against the chair, briefly closing his eyes, and it was a few precious moments before he spoke again, though when he did it had nothing to do with her.

“Simon, tell that boy to bring me more wine. I have a parching thirst. And tell him to be quick about it, for I must go to the castle to see how Edmund fares.”

Thinking perhaps he hadn’t heard her, she began again, “But sir . . . ?”

“Silence.” He raised his head, his brown eyes unreadable. “I have no wish to disappoint the Baroness, so I will have your loom brought here, and you can work on it for as long as necessary.”

Her chest tightened as did Simon Poyntz’s hold on her arm when he came to lead her from the room, the full import of what was happening pressing like a heavy weight on her chest. She was to be a prisoner. Simon’s expression was smug, and Adcock stared suspiciously at her, then turned to the Seneschal.

“Sir?”

“What?” Brutus snapped.

“The Bailiff told me I’d be rewarded for my loyalty.”

Brutus walked towards the man, who hunched his shoulders and bowed his head.

“You have told the truth, haven’t you? You heard the girl say those things?”

Sophia caught his eye pleadingly. She had given the man’s family some vegetables last month when their spring croft had been overrun by a cow, and she had given their youngest daughter some homespun in return for running errands. Although the girl was backward and slow, Sophia had let her take her weaving up to the castle, saving her a half-day’s trek from the cottage. But Adcock avoided looking at her.

“May the Absolute be my witness, sir. It is all true. I told you because I’m loyal to your lordship and to the Baron.”

Brutus waved away the man’s fawning subservience. “Go see Morwen. He’ll give you something.

Adcock looked disappointed. The steward’s reputation for stinginess was legend.

“Now all of you, leave me. I crave a few moments peace,” Brutus ordered, and they all trooped out.

Immediately upon entering the clearing, Emily missed the friendly smell of woodsmoke and thought it strange no fire was burning. In the dark she could tell that the cottage door hung open, like a gaping mouth, but when she called out to Sophia, the only answer was a plaintive moo from Blossom. Feeling her way inside, she realized the fire was indeed out under the continuous cauldron and she groped her way over to the corner, wondering if perhaps Sophia was already in bed, but the bed was empty. She stood in a quandary, puzzling where Sophia might be, when she was struck with the sudden realization that she hadn’t stumbled over or walked into some part of the loom while moving around–it took up so much of the small dwelling. Gone! The loom was gone. As her eyes adjusted to the dark she saw the gaping hole where it used to be and the reality sank in. Once, she had ridden a carnival ride that relied on centrifugal force and had spun around faster and faster until the floor dropped out from under her, and that was how she felt now, the same dizzy, woozy feeling that everything had dropped out from under her.

Wondering how long Sophia had been gone, she felt the continuous cauldron. It was still warm, so it hadn’t been too long ago. Should she go after her? Go where? Not now, not in the dark, she thought, shivering involuntarily. She’d have to wait until morning.

That night, she slept fitfully and awoke the next morning before it was light to the sound of Blossom’s positively piteous mooing. Working in the water meadow, Emily had gotten used to getting up early, so now she wiped sleep from her eyes and grabbed the pail and milking stool, hurrying outside. If nothing else, she’d have fresh milk for breakfast.

The poor cow’s udder felt hot to the touch, distended with milk, the skin stretched taut, and her teats dripping. Emily had milked her yesterday morning, but plainly the evening milking had been missed. Or was Blossom dripping milk because she was getting ready to calve. Emily sincerely hoped not, since she wasn’t prepared to deal with that at all. She dreaded to think what could have caused Sophia to leave and whether it had something to do with her.

After milking, she considered going to work at the water meadow but immediately pushed that thought aside. How could she do anything without first knowing about Sophia? The village was the place to start. Hadn’t Sophia said they all knew each other’s business?

Kneeling on the mossy stream bank to wash up, she splashed cold water over her face and head, shivering, then returned to the cottage and slipped on her clean tunic from May Day and her auspicious calfskin shoes. Feeling a little better, she turned her steps with determination towards Ephemera.

The low road into the village seemed strangely deserted. She found herself thinking wistfully of the deep shade in the forest, until she remembered the pool of lost opportunities. No, even though the sun was hot overhead, she’d rather be here. Outside the village she saw a few laborers hoeing a cornfield, but the corn was getting tall and they were bent low; no one appeared to notice her. Nor did the laborers on the other side, scything hay. With each step, her leather shoes raised a small puff of dust, dirtying them and her tunic. She slowed down as she entered the village. Before, she had gone there with Sophia; now, by herself, she felt shy and looked for Will or Thea.

The first person she came across was a woman bending over some straggly bean plants in a croft beside her cottage, a small house made of woven branches stuck together with mud, like Sophia’s. Two small girls played on the hard-packed earth in front of the open door, pouring dirt and pebbles into small piles, making little hills. A thin crying came from a basket on the ground and Emily realized the woman had a baby lying beside where she was picking. At the infant’s cry, she looked up and Emily recognized Isaac’s wife, Mary. She had met her once when she and Sophia had visited Isaac after his snakebite.

“Children, Bess, Alys, get back into the house. Do you hear me?” Hastily, she picked up the basket with the infant, using her other hand to hold the corner of her apron with the beans she’d just picked.

“Mary?” Surely the woman remembered their meeting, although she didn’t act like she heard Emily and was walking quickly into the cottage.

“Mary! It’s me, Emily. I met you once with Sophia?” She hurried to catch up with the retreating figure. “Mary?”she called after her. “Do you know where Sophia is?”

Mary emitted a small cry and ducked in the open doorway.

“Wait!” Emily hurried to the door, but Mary reached past her to grab the younger girl by the back of her dusty, oversized tunic and pull her inside the dark interior, then attempted to shut the door in Emily’s face.

“Wait, please! Can I just talk to you?”she pleaded, putting her hand on Mary’s arm. “What’s happened? Where is Sophia?”

Mary pulled her arm away and the infant in the basket began to bawl in earnest.

“Mary, please, talk to me!” but the door was abruptly closed.

Emily stood for a moment, dumbfounded, sweat trickling down the side of her face and down her back. Filled with dread, she headed towards the cobbler’s shop. On second thought, she turned towards the village school since it was still early enough in the day for children to be there. Because the wooden church was in the center of the village and she didn’t want to attract attention, she slipped around back and sidled up next to an open window, listening. They were reciting out loud.

“. . . you are the One, the Only One, the Absolute, . . . Your word we obey, . . . and do homage on bended knee . . . .”

She recalled Cyril saying that Tado Lawrence only taught the children their prayers and obeisance, not high Anglais or reading. The two windows in the church were stained glass, one with a picture of people kneeling at the edge of a forest before a rising sun, and the other of a man and woman, holding hands, about to enter the woods. Cautiously, Emily looked inside the church.

They were chanting, and inside the cool, dim worship area she could just make out a dozen or so children sitting on the floor.

“. . . to all the high priests . . . our ruling lords and their ladies . . . we offer our humble reverence . . . . Blessed be.”

The respetado stood before them in a brown robe saying the words, which the students dutifully repeated. Thea was up front, earnestly chanting along with the prayers; they were unfamiliar to Emily, but then her family had never gone to church.

. . . that woman receives her blessing from man . . . in holy mystery. . . .

Finally she located Will, his curly head bent, looking at the floor but chanting along with the rest. She had to catch his eye. Just then, as if sensing someone looking at him, he raised his head. When he saw her, his eyes widened but he quickly looked at Tado Lawrence, as if to make sure he hadn’t noticed her.

Emily sighed, sliding down the side of the building onto the ground, to wait.

Knees tucked up under her chin, she was idly wiping dust off her calfskin shoes when two men came around the corner. Quickly she hunched behind a scraggly witch hazel bush and listened as they spoke in low tones.

“He don’t have anythin’ to do with her, does he?”

“As a matter of fact, he does.”

She recognized the second voice as the cobbler’s.

“Don’t mention it, Jacob. Don’t say nothin’.”

“Do you think the Bailiff will come around askin’? I dare not lie to him. I only gave her a pair of shoes once that no one wanted. I should na’ ha’ done that.”

“Just say nothin’ and keep your family busy, workin’ and maybe . . . .”

“I have to get back. I’ve another pair of shoes to finish for Morwen today.

“Ole skinflint. Hope you get paid,” the other man said.

“He still hasna’ paid me for the last pair.”

Then they were gone.

Her heart pounded. The Bailiff was asking around about her? The cobbler wanted nothing to do with her? What had she done that was so terrible? People walked off their jobs all the time. But even as she listened to the chanting inside, she knew that different rules applied here.

When school finally let out most of the children went home for lunch. It didn’t take Will long to slip around back.

“Will, where is Sophia?”she asked right away.

He grasped her arm pulling her farther away into a small clump of trees, checking behind them as they went.

“What’s going on?”

He answered her question with one of his own. “Emilia, why have you come back?”

“Why shouldn’t I?”

Looking serious, he took both her hands in his.

“The Seneschal says you were fostering sedition, that you told Isaac and Cyril the land they farm is rightfully theirs, and that overlords are not necessary. Did you say those things?”

Abashed, she mumbled, “Well . . . I . . . I might have. Yeah, I guess I did, but so what?”

“Don’t you realize,” now he was looking abashed, “that people have been hanged for less?”

No, she hadn’t realized that, she thought, pulling her hands away. “It doesn’t have to be this way. Someone needs to stand up to them. You’re not being treated fairly.” But even as she said it, she felt the heavy weight of tradition settle over her, the inertia towards any kind of change, even for the better. And then there was the fear.

“Who’s going to stand up to the Seneschal,” Will hissed, “and sacrifice himself

. . . or herself? Besides, if you intend to change things, Emilia, you must stay around, not disappear into the forest.”

Stung with guilt, she said defensively, “I didn’t mean to,” but she knew that sounded lame. How could she tell him about the inviting coolness, the hypnotically sparkling dragon finches, and her excessive fatigue, maybe even heat exhaustion?

“Well . . . Adcock overheard you telling Isaac and Cyril and went straight to the Bailiff. Now they are being held for questioning, all ‘cept Adcock of course. The snitch.”

“Oh god,” she said with alarm. “What about Sophia? She had nothing to do with this.”

He shook his head despondently. “The Seneschal blames her because you’re her niece. Now she’s locked up at the manor house until you turn yourself in.”

“ ‘Turn myself in?’ ” she echoed. “That makes me sound like some kind of criminal, just because I couldn’t work any more. But if that’s what I have to do, then . . . ,” and she turned to go.

He grabbed her arm again. “You have no idea what he’ll do to you. He’s telling everyone that Sophia is a witch and you’re her familiar. That you do her bidding.”

“That’s nonsense. No one’s going to believe that.” But Will’s usually twinkling brown eyes were somber. “This is all because of . . . ? It makes no sense.”

“He also says you’re a heretic and has told the whole village he wants you found. Anyone hiding you risks offending the Absolute, and all the punishments that come with that.”

“What slander has he not spread about me?” she said sarcastically.

“Slander or not, people must obey him.”

“Listen Will, I have to get Sophia out. I can’t just leave her there.”

He looked skeptical. “You don’t know what it would take. You’ll need help.”

“I don’t want to get you involved.” She remembered his father’s concern.

“Too late. I already am, because we’re friends. Anyway, I have an idea how we’ll get in.” He reached in a pocket and she thought, improbably, that he might have a key to the Senechal’s manor house, but instead he produced a hardened crust of bread, handing it to her. “Here. Thought you might be hungry.”

Despite what was happening, her face softened. He really was one of the nicest boys she’d ever met.

They arranged to meet later that day after dark, behind his family’s croft.

. “Until then, try not to be seen, Emilia” he cautioned and left to go work in his father’s shop.

She headed out of the village to wait, careful to stay away from the water meadow and more conscious now of the laborers working in the field as she walked the low road. Still, no one acted as if they saw her. She thought that maybe she had become invisible. That would be helpful in order to sneak into the Seneschal’s. She found a hiding place in the forest where three trees grew close together with a tangle of grape vines clustered among them and extending to the ground, making a tent of sorts. A thick layer of accumulated dead leaves made her comfortable, and she again sat with her knees tucked up under her chin and gathered dead leaves around her like a cloak of invisibility. She really did wish to disappear.

Listening to sounds in the forest around her, she was alert for any footsteps or hoofbeats. Instead, all she heard was birdsong, a cardinal trilled nearby, crows cawed to one another, and far overhead, a hawk screamed. Underneath the grapevines was the steady hum of flies, bees, and probably mosquitoes. No leaves stirred; not a breath of air was moving.

Maybe if she kept her body still, her mind would follow. Right now, it was like an ocean during a hurricane, a mad tumult of thoughts about fairness and inequality, about land ownership and overlords, about religion and intolerance. Like Pandora, she had unwittingly unleashed a storm just by telling them there was another way, and Sophia, the person who had been kindest to her, was paying the price. She wanted to blame Simon Poyntz but she knew there were bullies everywhere, like Damien Heller at school. Simon wouldn’t even believe she’d gone to school or could read. Knowledge really was power. But Sophia couldn’t read, and she had her own kind of power. Why couldn’t she use that to get herself out of the manor house? Confused, Emily lay down in the leaves, anxious for her friend but knowing that she just had to wait.