The Homestead Gardener

The Fireplace in the Library

(A Shoulder-Season Reverie)

- DERRICK GENTRY –

In the south-facing room where I now sit typing these words, the shambolic haven for half-read books that we somewhat pompously refer to as “the library,” there is a certain slant of light late winter mornings and afternoons that forms a little patch of passive radiant solar heat on the floor of the room. My dog and my cat like to curl up or stretch out in that oasis. (I am seeing a bit more of the latter than the former these days). The woodstove, generating mostly convective heat, is located two rooms and about 70 feet away. The day your dog prefers passive solar to stretching out beside the woodstove in the other room, that is a sign you have entered what is known in temperate climes as “shoulder season,” that betwixt and between period, lasting a couple of months, stretching awkwardly between one season that has ended and another that is struggling to be born.

Our house, an early post-colonial structure built in 1821, is turning 200 years old this season. We are not sure how to throw a bicentennial party for a non-person, even though it feels like we ought to mark the occasion in some way. Not all of the house is the same age, of course: the windows of the south-facing room that let in the light are now double-paned modern windows with much better R values, and most of the original plaster and period wallpaper has been replaced with drywall and Valspar paint with an egg-shell finish. But the structure of the house remains, and many of its original features are still in place after two centuries.

They did not have diesel-fueled excavating equipment back in 1821, and careful thought therefore had to be given to the local topography of the site where a house would be built. Our house was wisely built into the side of a hill. The massive rock foundation forms a multi-room basement that is remarkably well insulated during the winter—in fact, even on the coldest days in January, the basement is barely cool enough to serve as a root cellar and apple closet.

In the basement, on the side where the west chimney stands, there is an old-fashioned fireplace once used for cooking, with side compartments for baking and an iron swivel-crane, still attached and ready to be used, that once held heavy cast-iron pots above the flame. Our house was a major stop on the Underground Railroad during the 1850s, and when I am in what used to be the cooking area of the basement I sometimes try to envision newly arrived guests gathered around the fire in the basement and enjoying a meal before departing on the next leg of their dramatic journey. These guests may have been offered familiar cornbread, but probably not the sweet potatoes they grew and cooked down south. I wonder how these recent refugees from a different latitude responded to the colder temperatures they were encountering as they moved farther and farther North.

I often wonder, more generally, how people back then kept themselves warm in the dead of winter. The answer, it seems, is that they mostly didn’t—or, in many cases, not much warmer than is necessary to avoid freezing to death.

One of the books my wife is currently reading, that is now sitting open on the table beside the library fireplace, is titled At Home: The American Family 1750-1870. It contains some rather chilling accounts of how people kept marginally warm when burning wood and snuggling were the only source of heat. In the late 1700s, for example, Jane Mecom told her brother Ben (Ben Franklin, that is) how she had endured a Boston winter with only twelve cords of firewood, “as we kept but won Fire Exept on some Extyroidenary ocations.” (These period accounts also tell us something about how people lived and communicated before standard spelling…) Abigail Adams, trying to keep a family of eighteen warm at a home just north of New York City, reported burning 40 to 50 face cords a year, “as we are obliged to keep six fires constantly, & occasionally more.” Writing a bit later in the 19th century, Harriet Beecher Stowe writes of her aunt standing with her back to the fire while a wet dishcloth in her hand froze stiff in the cold air of the room. Perhaps most distressing to our ancestors, there were some days during the season that were cold enough to freeze rum stored in bottles inside the house.

As the 40 to 50-cord heating budget suggests, Americans back then may have had to work within the limits of their excavating technology, but in the 1700s and early 1800s there was still a lavish quantity of firewood to burn. (I looked at my wife in disbelief when she first read that figure to me: I have a hard-enough time gathering 10 cords per season, and I simply cannot imagine the task of cutting, splitting and stacking up 40-50.) Why did they burn so much wood and still struggle to stay warm? It certainly had nothing to do with the quality of the firewood. It simply had to do with the fact that the energy efficiency of the early fireplace was ridiculously low by our standards. Something close to 90% of the heat generated from burning wood literally went up in smoke and out the chimney. And to add insult to inefficiency, much of the smoke would pour into the poorly heated room in the absence of a strong updraft in a standard, poorly designed chimney.

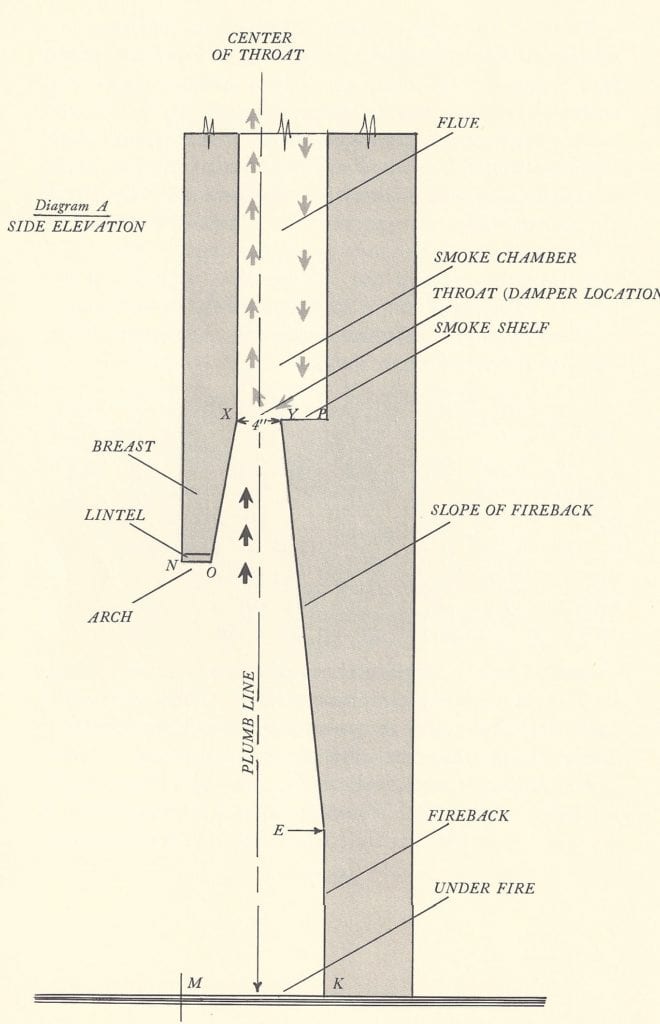

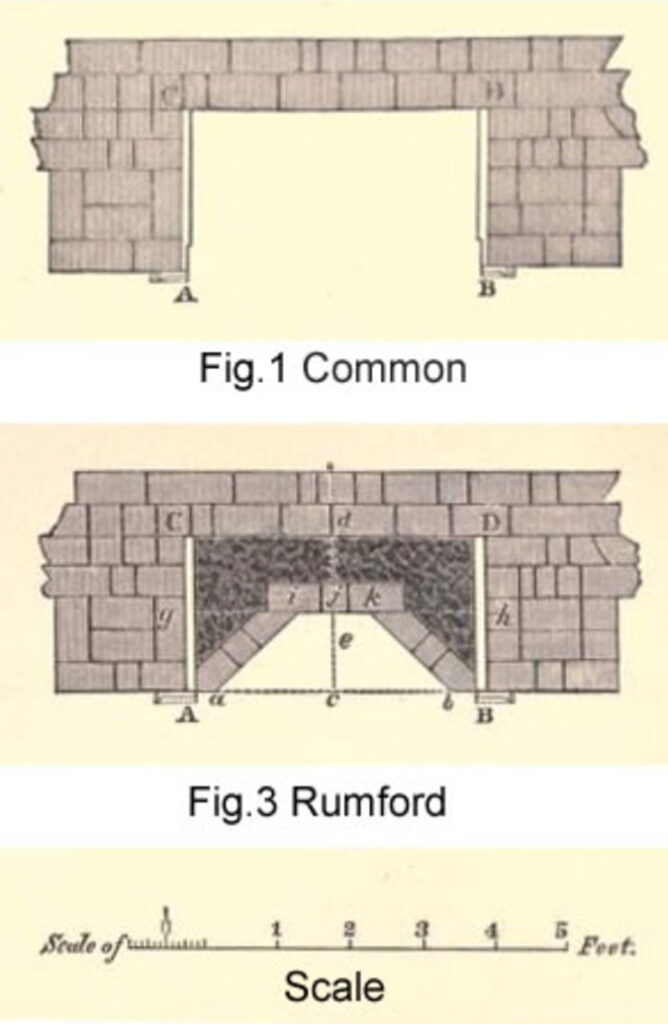

Above: Schematics of the Rumford fireplace, which revolutionized wood-fueled heat in the 1800s. Common & Rumford fireplace diagrams: Rumford, Benjamin, Graf von, Not In Copyright, Internet Archive

Below: American-born scientist and inventor Benjamin Thomson (AKA Count Rumsford). Popular Science Monthly, 1907, artist unknown

That is why the Rumford fireplace represented such a breakthrough in the early 1800s. (The oft-reproduced schematic is reproduced once again on this page.) Named after the American-born scientist and inventor Benjamin Thomson (later renamed Count Rumford), the Rumford fireplace had angled sides that reflected more heat into the room. More importantly, the new chimney had a much narrower passage, generating a stronger updraft of air that pulled the smoke up and out. The narrower chimney was also designed to divert and trap the hot air in its passage upward in a chamber where, under ideal conditions, the exhaust would undergo secondary combustion that generated even more heat (and less smoke).

In the early 1800s, the Rumford design was what we would now call an energy-efficiency retrofit innovation. It was a big hit. Thomas Jefferson, who just loved this sort of thing, immediately had all his fireplaces at Monticello retrofitted. By the mid-1800s, Thoreau listed the Rumford fireplace on his list of modern conveniences that were taken for granted. Rumford, by the way, also invented a number of other homely modern conveniences, including the double boiler and the coffee percolator.

Back to the present, in the front-parlor library of the home where I sit with dog and cat on this sunny late winter day, the At Home book I quoted from earlier now sits open on a table that stands in front of an unused fireplace that is one of the earliest examples of the Rumford design. (I promise I did not put the book or the table there myself! I do not engineer poetic irony…) Our Rumford fireplace has not had a fire in it for many years. The smart-design brick chimney has been blocked off for years, and the purely decorative fireplace is simply an interesting relic and sometimes an interesting conversation piece for those who do not know the history.

There is another interesting story to tell about this south-facing room with a Rumford fireplace, particularly for those who appreciate the poetic ironies of history. One of the earliest and most illustrious guests at this house after it was built was Gilbert du Motier, better known as the Marquis de Lafayette. Lafayette stayed here as an invited guest during his Grand Tour of the United States in 1824, and he very likely warmed himself beside the Rumford fireplace in the front parlor room that is now our library.

Rumford and Lafayette, the Count and the Marquis, were both refugees of different revolutions. They both learned the hard way that not every revolution goes quite the way we want it to go (and not every disruptive change is geared toward human-scale betterment).

Rumford was born without a title in Massachusetts colony, under the name Benjamin Thompson. Both a native-born American and British subject, Thompson expressed sympathy for the loyalist cause in the early years of the American Revolution. This view did not endear him to his neighbors. He learned that while tolerance of the most unpopular opinions is the true test of the principle of free speech, in America and elsewhere in the world you can make things much easier for yourself, and get much nicer treatment from neighbors and co-workers, if you adhere to popular opinion. A mob of his neighbors gathered at his home and asked Thompson to rethink his opinions or get out of the country that was about to be formed.

Upon leaving America for England, Rumford wrote to his father-in-law in Concord, Massachusetts: “Though I foresee and realize the distress, poverty and wretchedness that must unavoidably attend my Pilgrimage in unknown lands, destitute of fortune, friends, and acquaintances, yet all these evils appear to me more tolerable than the treatment which I met with from the hands of mine ungrateful countrymen.”

Rumford was wrong; he went on to enjoy great success and fame in Europe (the land of opportunity, where apparently you can grow up to become a Count).

The fortunes of the Marquis de Lafayette took a similarly dramatic turn once the American Revolution that brought him fame was over. When he returned to France in the political hotbed of the 1780s and 1790s, Lafayette was regarded as a hero of the last revolution, one that took place in a different country and looked less radical than the one shaping up in Lafayette’s home country (home of another efficiency innovation of the 1790s: the guillotine). Lafayette also came from an aristocratic line and had a stand-out title to go with his name, which also looked bad in the context of the new revolution. In 1791, a mob of revolutionaries gathered around his home and inspired him to flee France for his safety. He was arrested while in flight and spent five years in prison, including a full year in solitary confinement. The new regime seized all of his property, leaving him homeless and penniless, and shortly thereafter he was stripped of his French citizenship. (And though he remained an honorary citizen of the United States, that was a privilege he was not allowed to enjoy while imprisoned in his home country.)

Back in Paris, his wife Adrienne, the Marquise de Lafayette, narrowly escaped the guillotine as a result of the shrewd intervention of her close friend, Elizabeth Monroe, who was the wife of the then-ambassador to France from the United States. Adrienne was imprisoned for many years and died in 1807 of complications from an illness that stemmed from her time in prison. Her dying words to her husband were “Je suis toute à vous” (“I am all yours”).

Rumford, who had left his first wife behind in America, went on to marry the widow of the scientist Antoine Lavoisier, who had been sent to the guillotine in 1794. The former Benjamin Thompson of Woburn Massachusetts died in Paris in 1814.

In 1824, invited by Elizabeth Monroe and her husband (who had since gone on to become president), the now elderly and widowed Marquis de Lafayette made his solitary return visit to the United States, to the country that he loved and where he perhaps felt most at home. He received a hero’s welcome when he arrived in New York City in August.

I hope the Marquis was able to enjoy some peace and rest during the time he stayed at my house in this late season of his life. It must have been October or November by the time he had made his way north to my part of the state. And I hope he was able to stay warm and comfortable as he sat by the fire, courtesy of Benjamin Thompson. From where I sit by the window, I can almost imagine the Marquis, looking tired but content, seated by the fireplace in a state of reflective reverie, which is what fires in the fireplace tend to inspire (then and now).