Upright Women Indeed

REVIEW from MAUREEN MCCARRON

Referenced in this Review:

The Book Woman of Troublesome Creek by Kim Michele Richardson

The Giver of Stars by Jojo Moyes

Review by Tomi Obaro, buzzfeednews.com (October 7, 2019)

Upright Women Wanted by Sarah Gailey

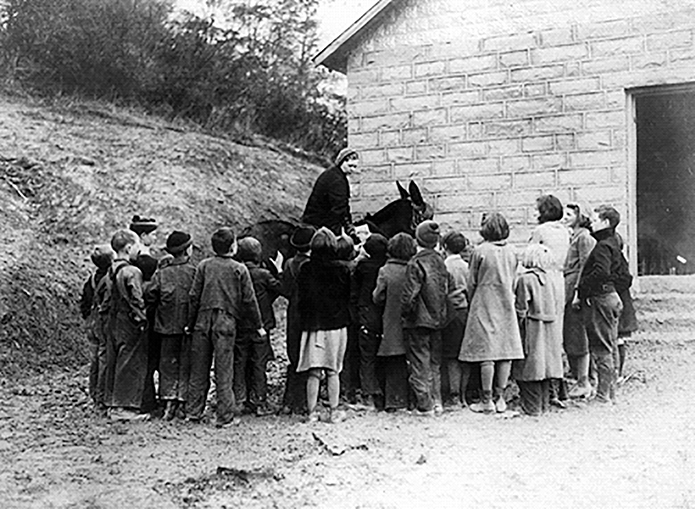

“Works Progress Administration Pack Horse Librarians make regular calls at mountain schools where children are furnished with books for themselves and books to read to their illiterate parents and elders.” Public Domain, 1938

It is not often that librarians are depicted as super heroines. To my delight, two recent books do just that: The Book Woman of Troublesome Creek by Kim Michele Richardson and The Giver of Stars by Jojo Moyes are colorful fictions describing the very real lack of library services in rural Appalachia in the 1930’s. “Because of the Great Depression and a lack of budget money, The American Library Association estimated in May 1936 that around a third of all Americans no longer had’reasonable’ access to public library materials.”

The packhorse library initiative began in 1913 when the Kentucky Federation of Women’s Club started the program (which stopped a year later after the death of a wealthy benefactor. It resumed again in 1934, through the New Deals after the Kentucky Federation of Women’s Club solicited the WPA for its reinstatement.*

The Progress Administration (WPA) program delivered books to remote regions in the Appalachian Mountains between 1935 to 1943. Pack horse librarians were known by many different names including “book women,” “book ladies,” and “packsaddle librarians.” The project helped employ around 200 people and reached around 100,000 residents in rural Kentucky.” (en.wikipedia.org Pack_Horse_Library_Project.)

So, it was with dismay that I learned that these books about the Pack Horse Library Project are embroiled in a publishing controversy that, before the wholesale consolidation of media, I believe, would have never occurred.

The Book Woman of Troublesome Creek by native Kentuckian Kim Michele Richardson was published in May 2019 and The Giver of Stars by UK writer Jojo Moyes was published only five months later, in October 2019. Both books are about fictional characters employed by the Pack Horse Library Project. Although I have read and liked several of Moyes’ books, I was very dismayed to learn in late 2019 that Moyes was accused of serious plagiarism. I refer readers to the very detailed comparison of both books in the review by Tomi Obaro in buzzfeednews.com (October 7, 2019.)

Obaro published Richardson’s detailed accusations (quoting both chapters and page numbers) including numerous and striking similarities between the two books. Those semblances include: similar characters, plot conflicts, and romantic liaisons; fatal mule tramplings; references to the same Pulitzer Prize winning book of 1932 and the Women’s Home Companion; poetry books as romantic gifts; legal challenges, including jail time for characters; the month and the weather at weddings; and the age and sex of the infant character in both books. As other reviewers have pointed out, historical events can be legitimately interpreted by different writers through different lenses and coincidence is always a possible explanation for the similarities between these books.

One of the most striking differences is Richardson’s casting of Cussy Mary Carter, as her main pack horse librarian character. Cussy was named after the village of Cussy in north west France, from where, we are told, one of her ancestors emigrated. Cussy is described as one of the Blue People of Kentucky. There were, actually, very real Kentucky Blue People, descended from the French orphan Martin Fugate, who researchers speculated had the rare blood disorder called congenital methemoglobinemia. At mild levels this condition can make Caucasian skin look “blue” due to an enzyme deficiency that alters hemoglobin, reducing its oxygen-carrying ability in the blood—hence the “blue” tinge it lends to white skin. Fugate, who from historical records at the time was described as “looking blue,” immigrated to rural eastern Kentucky in 1820 and married a normal-looking local woman who, against incredible genetic odds, also carried the recessive gene for methemoglobinemia. Out of their seven children, four appeared “blue.” In the 19th and early 20th centuries there was no known diagnosis or treatment for such conditions and this striking personal appearance could and did invite ridicule and social shunning.

Nevertheless, the Fugates met and married other local people and continued to have “blue” children into the mid 20th century when the condition was documented, and treatments were prescribed. In Richardson’s book, a local doctor helps diagnose Cussy’s condition and prescribes a treatment. However, as the author herself points out, that actual medical work occurred in the 1970’s, not the 1930’s.

Richardson uses the blue-looking skin from methemoglobinemia to explain the profound social rejection her character Cussy experiences. In Moyes’ book, one of her main characters is an English woman who, after she moves to eastern Kentucky with her affluent American husband, is trapped in an abusive marriage. Another pack horse librarian character in Moyes’ book is a survivor of chronic childhood domestic abuse. In both books the female characters are ostracized due to or by their experiences and rail against the social conditions of the time, which tolerated marital and domestic abuse against women with little recourse for the survivors. Both books also feature sympathetic African American women characters portrayed as working in the WPA pack horse library program.

However, as reviewer Tomi Obaro writes in buzzfeednews.com, African Americans were never employed in that WPA program.

Nevertheless, Richardson casts the blue skin color of a person with methemoglobinemia as the explanation for why two of her characters are accused of “racial mixing” when they marry, and the husband character is prosecuted for miscegenation and imprisoned. Granted, this book is set in the early 20th century, and while it is well documented that African Americans and other people of color experienced that form of discrimination (anti-miscegenation laws were in effect in Kentucky from 1866 until 1967), I found Ms. Richardson’s use of methemoglobinemia as grounds for invoking those laws, even in a fiction, rather incredulous.

Moyes’ book is distinguished by how she depicts the friendship of five pack horse librarians in her fictional town of Baileyville, Kentucky. Both books do a good job of illustrating the poverty and limited literacy experience of their library patrons, and both show the pack horse librarians improving both the literacy and the emotional life of the isolated families on their routes. Both books describe the Pack Horse Library Project as improving impoverished rural schools in eastern Kentucky at the time.

There are many reviews of these two books on-line. I found them divided into two camps: well-established authors, published by large media companies, tend to give Moyes the benefit of the doubt and refrain from the plagiarism charges. Less well-established authors, especially those who are loyal fans of Richardson, have “cried foul”.

However, no reviews I found questioned the role of the publishers involved. I have always thought a publisher did some “due diligence” before publishing a book. According to Melissa Gouty (literaturelust.com) Moyes sent a rough draft of The Giver of Stars to her editor at Penguin Random House in October 2018, a full year after Richardson’s completed book had already been sold to her publisher, Sourcebooks. Did the Penguin Random House editors do even a simple Google search on the unusual topic? Why didn’t Sourcebooks, who already had the copyright, raise the issue with Penguin Random House?

A possible clue is the timing of Sourcebooks’ sale of a significant minority ownership of their stock to Penguin Random House on May 22, 2019. Richardson’s The Book Woman of Troublesome Creek was released by Sourcebooks just fifteen days earlier on May 7, 2019. Did either of these publishers care? Apparently not. Since, after the fact, Sourcebooks gave Richardson the option of seeking her own legal counsel.

Moyes, whose book has definite cinematic qualities, sold the movie rights in June 2019 (the-bibliofile.com/giver-of-stars-movie-release-cast-trailer-film/) just after The Book Woman was published but also well before her own novel, The Giver of Stars, released by Penguin Random House on October 2, 2019. The high-minded advise us to read both books and come to our own conclusions.

So, it appears that even the topic of librarians themselves is not free of controversy. This is probably no surprise to actual librarians. However, this conflict reminded me of a third recent book, by Sarah Gailey, whose title (from the recruitment poster for the librarians in her book) is practical advice: Upright Women Wanted. Gailey reinvents the pulp Western, in a near-future dystopian American Southwest. Her itinerant librarians also serve heroically, along with a good dash of edge-of-your-seat adventure.

Fortunately, for us here in the Finger Lakes, many of our libraries weathered the Great Depression without closing. Communication with the county historians of Livingston, Steuben and Ontario counties also told me that the WPA Pack Horse Library Project did not need to operate in our rural areas. Some rural parts of New York State did have book mobiles (library vans). My local library currently runs a “delivery program for shut-ins,” and so the tradition of getting books out to those who need them most is alive and well. Read on!

*Correction / clarification provided by an assistant to Kim Michele Richardson, April 8, 2021 clarified that Eleanor Roosevelt was a strong supporter of the initiative, but that it was started much earlier by the Kentucky Federation of Women’s Club with the support of a private benefactor.

Maureen is a retired speech pathologist, living in Conesus, NY who now spends her free time reading to her heart’s content.