The Homestead Gardener: Going Wild and Going Native

- By DERRICK GENTRY –

As Spring Planting Season Draws Near, Consider Native Plants for Your Garden

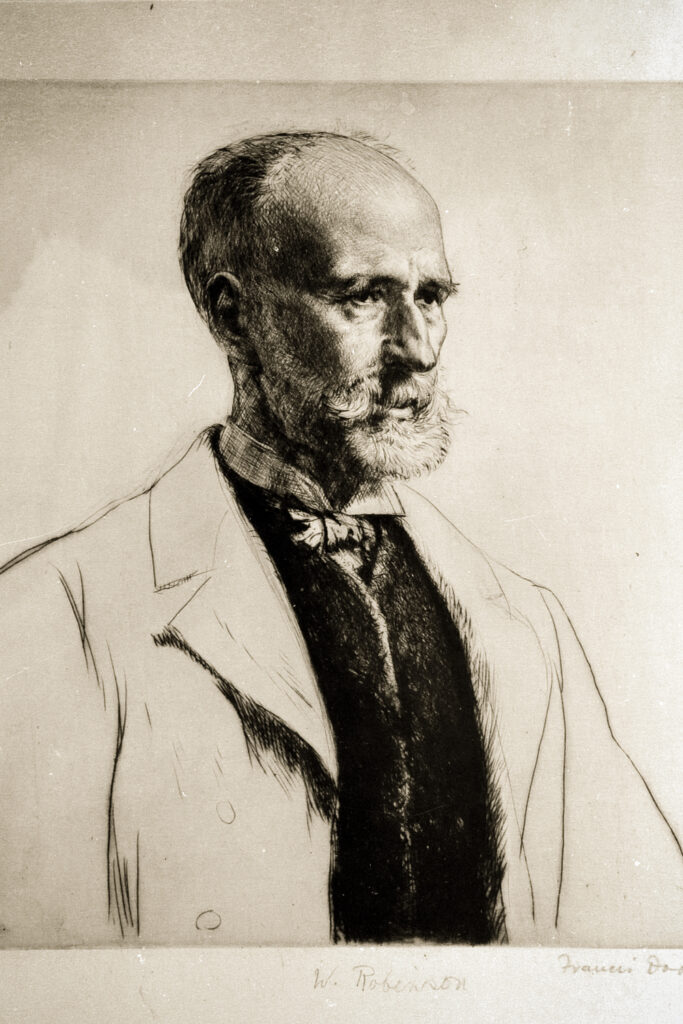

Englishman William Robinson’s book The Wild Garden is one of those classic revolutionary books that retains the power to provoke. That really says something about a book published a century and a half ago (first edition appearing in 1870). The reasons for The Wild Garden’s perennial interest are perfectly clear. Although it has gained momentum in recent decades, the revolution that Robinson called for has barely begun. At the dawn of this century, moreover, there has never been a more urgent need to rethink gardening in the way Robinson proposed.

The very title of the book remains provocative. Isn’t a wild garden a contradiction in terms? Isn’t a cultivated garden by definition not the same as wild nature? We don’t weed or prune or mulch the woods, do we? All of which leads to the common suspicion that a wild garden is perhaps just another name for what our neighbors fear: an unkempt, unweeded garden that grows to seed. (“Fie on’t! Ah, fie!” cry the counter-revolutionary neighbors.)

Robinson was certainly an advocate for designing gardens that were low-maintenance and what we would now call resilient. And he had many things to say that sound like familiar rallying cries of today: Stop mowing so much lawn (and this before the time of gas-powered mowers); go with native, wild plants rather than fussy exotics; plant easy-to-establish perennials, as opposed to the more labor-intensive bedding out of annuals. Perhaps most importantly: Learn to appreciate the aesthetics of spontaneity, live with and embrace the delicious paradox of cultivated wildness.

Robinson knew he was a bad boy shaking things up, and The Wild Garden is just plain fun to read on that level (his personality coming through on just about every page). But while still an exciting book to read, it also contains passages that are likely to provoke a different response from a 21st-century reader. He was not opposed in principle to non-

native plants, so long as they had aesthetic interest and could look out for themselves—hardy perennials, reliable self-seeders. In hindsight, though, it is painfully clear that Robinson sometimes failed to distinguish between the vigorous plants that could naturalize on their own and those other robust, eager-to-naturalize plants that we would now designate as “invasive.”

One non-native plant he singled out for praise, as having “large and noble tufts of lively green, which increase in beauty from year to year” and as a “capital plant for the small-town garden,” so long as it wasn’t allowed to get too big and go to seed. The plant he is describing here is giant hogweed, which is now one of the most dreaded invasive species in North America. Somebody, apparently, allowed it to get too big and go to seed! Robinson expressed similar enthusiasm for Japanese knotweed, another invasive that needs no advocacy today (at least not where I live).

Robinson, in short, did not have a modern grasp of ecology and did not prioritize biodiversity in quite the same way we do today. On the other hand, The Wild Garden is filled with many reminders and qualifications that a 21st-century reader would do well to hear. In his bold but subtle way, Robinson was trying to redefine the role of the gardener, not relinquish it in the interests of that problematic ideal known as “rewilding.” Biodiversity does not just happen as soon as we step out of the picture and let nature take its course, as soon as we stop mowing the lawn and stop cutting down dead ash trees. Invasive species—garlic mustard, water reed, purple loosestrife, Japanese knotweed, and many more—are ready and waiting to step in and fill the vacuum and prevent other species from getting a foothold. It is worth noting that many of these ecologically devastating invasives are quite pretty. And then there are the hungry deer who will clear the landscape of any unprotected tree saplings and prevent a future overstory from replacing older generations of trees that have been cut down (or that are dying from pests and diseases that humans have brought into the picture).

And so the gardener today who wants to carry on in the spirit of William Robinson now faces a more complicated task and must contemplate a far more complex vision than he did, and one that carefully avoids any simplistic notions of wildness. Today we value native, locally adapted species as much as Robinson and his equally legendary friend Gertrude Jekyll, but for a greater depth and range of reasons than they were able to appreciate in their day. When we talk of a flowering plant’s “period of interest,” we now need to take into account various points of view, including not just shapes and colors but also the interests of birds and insects and wildlife. Regenerative gardening (as good a term for it as any) requires the gardener to be a visual artist and lover of plants as well as a student of ecology.

Nevertheless, many of the guiding values are still recognizably those of the traditional gardener. In Gertrude Jekyll’s iconic herbaceous border, for example, the challenge is to design a panorama with a constant and carefully timed succession of color and “interest.” We can aim for something similar in a wild woodland garden, even though a walk through the woods is not a straight or even path. The main difference is that out in the woods we need to up our game a bit and train ourselves to think spatially, temporally, as well as systemically. A healthy and aesthetically beautiful woodland should have multiple layers: tall, majestic trees providing an overstory (ash, maple, oak, etc.); shade-tolerant trees nestling in the understory (dogwood, serviceberry, witch hazel, elderberry, etc.); and then the herbaceous layers below, where we see an ever-changing cast of Spring ephemerals and late-bloomers and everything in between, and where it is often surprising to see such magnificent color in near-total shade.

There is a lot to think about and a lot to learn. I have recently learned, for example, that Mayapple, stonecrop and wild ginger can share the same space and make an excellent groundcover polyculture in the dappled shade of a woodland garden “bed.”

But I am still a novice, still cultivating my wild ways, and I confess to sometimes feeling overwhelmed. Fortunately, there is help available. The spirit of Robinson and Jekyll is alive and well at Amanda’s Garden, one of only a handful of native plant nurseries in our area.

(Image: Amanda’s Garden)

For those who know it and love it, Amanda’s Garden is something of a local institution, and its founder, Ellen Folts, offers a wealth of generously shared wisdom and expertise on native plants and the role they play. Ellen has gone completely wild and native and has spent much of her life promoting the twins causes of beauty and biodiversity. She is a well-known consultant, and in addition to individual gardeners her long list of clients has included Central Park, Letchworth State Park, and the Roemer Arboretum at SUNY Geneseo.

Named after Ellen’s now fully grown daughter, Amanda’s Garden has been in business for three decades. In 2016, the nursery moved from Springwater to Dansville, to escape a quarter-century of increasing shade from an overstory of oaks (overhead costs?).

And mention must be made of the Amanda’s Garden website, amandasnativeplants.com, which is a wonderful resource of gorgeous images and information on individual locally adapted plants (grouped into “woodland,” “meadow,” and “wetland” plants). If you go to the website, you will see at the bottom right of the screen an image of Ellen with the words “let’s chat!” I once took her up on the invitation and discovered that she really means it.

What follows is a transcript of a recent chat with Ellen that took place a couple of months before the debut of the skunk cabbage…

How did you first develop a passion for the cause of promoting and propagating native plants? How did Amanda’s Garden come into being?

When I was young my hobby was identifying wildflowers. I had a field guide I carried with me and I would try to learn the flowers that grow in the wild. I lived in the Adirondacks until I was 14. Growing up there I was used to seeing plants in the wild. I fell in love with wild plants. My sister and I had a cutting garden with non-natives too.

Amanda’s Garden came into being because I worked in a Nursery growing ornamental plants. We did a lot of propagation. Every once in a while, someone would come in and ask for a native plant. Mostly plants like bloodroot and Blue eyed grass, that type of thing. I was growing native perennials in my own garden. The native wild plants had become my passion, particularly the woodland types.

These take a while to propagate from seed due to many species having double dormancy of the seed. One day I said to a coworker I should grow and sell these plants. I started collecting seeds and sowing them. About two to three years later I was ready to open. The first year we opened I had very few plants and only about 10 species.

Why did you move from Springwater to Dansville? Has your operation changed at all since the move?

We moved the nursery because it was behind our house which is on a hill. The forest behind our house is mostly oak and as the trees grew larger the canopy closed. We lost a lot of sunlight. It became difficult to grow some sun loving species because of this. Pollinator plants were becoming more popular due to their ability to support many insects. Many of the sun loving plants that flower in the summer need full sun. We looked for a level property that would get plenty of sun, had shady areas, had a water supply, and would keep snow cover throughout the winter. Perennials are subject to winter kill if the crowns are subject to freezing and thawing temperatures. The snow protects them from that.

The move helped us to double our production. We have a potting shed that has all the necessary equipment to make potting and seed sowing efficient. We have areas to overwinter the flats with the seeds that keeps them orderly and safe. We have 14 more growing frames and 7 raised beds for stock plants. We have a large production bench for custom sows. We have benches to display our plants with description cards. People have a lot of space to come and wander around. There is a table for picnics, a bench near the pond to watch the dragonflies, butterflies and other insects. We have a trail for use when it’s not too wet.

More and more people seem to be aware of why native plants are important, but would you review some of the reasons for choosing native plants over non-native? Do you find that a case still needs to be made for going with native plants?

As gardeners, what we plant can and does make a difference. Native plants are desirable not only because they are lovely to look at, but also because they are the right plants for the ecological community in which they are planted. Native plants assist in the survival of native flora and fauna. They co-evolved with native bees, butterflies and birds. They provide food, cover and habitat for these species that alien species simply cannot. Planting native species helps to preserve and recreate native habitats. Creating corridors for migrating native birds and butterflies increases their chance for survival in the face of development and introduction of alien species.

Gardens that include native plants require less maintenance since they are adapted to local conditions. They are also more resistant to pests because of their local genetics. At Amanda’s Garden we grow most of our plants from seed collected from local sources. Because we grow many of our plants from seed, they are not genetically identical and they can continue to adapt to changing pests and conditions.

In my experience, many people don’t know the value of using native plants. I find that when people are educated about the connection between wildlife and plants they are very excited about choosing native plants. When people come to the nursery and see a butterfly and you can say, “That is a fritillary butterfly; its host plant is a violet. If you want them to be at home on your property, you need violets.” They start making connections.

We like to contrast native plants to invasive species, even though “non-native” does not necessarily mean “invasive” and a number of aggressive “invaders” (such as the common dandelion and the black locust tree) have since naturalized and now play a beneficial role in the ecosystem. Can you talk a bit about the basis for distinguishing between native and invasive?

I would say that because plants are native that does not mean they aren’t invasive, and conversely non-native isn’t always invasive.

Natives such as cattails can overrun a wet area. Canada anemone can overrun a small garden. Plants need to be used properly. The problem occurs when non native plants are used or escape into areas where they out compete our native plants. Many of these non-native produce a lot of seed or are dispersed by birds. With no natural enemies, they overrun our native plants so we lose genetic diversity.

We are still in the middle of winter, and apart from Red Osier there is little color out there at the moment in the woodland garden. Take us on an imaginary journey over the next three seasons, and tell us about some of the visual highlights that we can look forward to — about what we might see simultaneously in bloom at a few different moments between early Spring and the end of the year, and about some of your personal favorite combinations/juxtapositions of woodland plants…

In the early spring, March, we will see skunk cabbage, beautiful spath enclosed flowers. The plant actually produces heat to melt the snow so flies and other early insects can pollinate it.

The next plants in April, Dutchman’s Breeches, Bloodroot, Trout lily, toothwort and hepatica (all beautiful and welcome after the winter)

Later in April into May, we see blue cohosh, wild leek leaves, trillium, woodland phlox, foam flower, wild geranium, early meadow rue, merry bells, wild ginger and wood poppy

Late May into June, the false Solomon’s seal, wild columbine, willow blue amsonia, Virginia anemone, Spiderwort, Penstemon, goat’s beard and golden alexanders show off in the garden.

June into July, Monarda, both bee balm and wild bergamot, turk’s cap lily, Canada lily, black cohosh, black eyed Susan, blue eyed grass, Swamp milkweed, white wood aster and summer phlox.

August brings both lobelias, cardinal flower and great blue lobelia, as well as wild senna, green coneflower, mountain mints and anise hyssop.

In September we see goldenrods, Blue stem, zig zag in the shade, showy and stiff in the sun. Asters like New England, New York, flat topped white aster and smooth aster. There are the beautiful mauve flowers of Joe Pye weed, purple flowers of ironweed, yellow flowers of wingstem and white turtlehead.

October is the lovely lingering flowers of asters and blue mist flowers.

(All images provided by D. Gentry)

I am particularly fond of combinations of foamflower, woodland phlox, yellow wood poppy and early meadow rue. Adding some sedges and ferns make the garden look more natural. Virginia anemone, wild columbine add continuing color. Black Eyed Susan, white wood aster and bluestem goldenrod keep the pollinators happy while keeping color in our garden.

For a moist soil red cardinal flower, bluestem goldenrod and bottle gentian are a stunning combination.

Many people around here have been cutting down dead and dying ash trees and hemlock and altering the overstory of our woodlands. Do you have any thoughts about what kinds of trees we might plant to restore and provide a canopy for the native understory plants that we have talking about? Are there any beneficial native trees that deserve special mention?

Oaks: plant lots of acorns and small oaks, and you are getting the best bang for your buck with caterpillar production. Caterpillars are what our songbirds need to rear their young.

Native cherries are great too.

It seems to me that nurseries like yours follow an interesting business model. Once you give someone a plant and teach them how to divide and save seed and graft and take cuttings on their own, you are essentially teaching them how to be less dependent on people like you. How do you see yourself as educator/advocate/business proprietor? How do these roles relate to one another?

There are not enough native plant nurseries. Especially when you consider it is best to plant plants with local genetics. I am happy to help people learn to grow their own plants. People can grow their own non-native plants, too, but many people choose not to. It isn’t as easy to grow quality plants as people think. We grow for the people who choose not to or who don’t have a lot of success or who don’t have the time to grow their own. There is a lot of space that could be planted with natives. I don’t worry about spreading the knowledge I have. As people are becoming more aware of the value of native plants, they will want them in their own gardens. This becomes our market.

Thank you, Ellen! Thanks for all the great work you do, and for always being there when we have a question.

Amanda’s Garden

8030 Story Road

Dansville, NY 14437

585-750-6288

https://www.amandasnativeplants.com/