Getting Personal

One of our writers recently shared, “I have been measured in my past writings; I do not believe I can be quite so measured in my November piece.” For the most part, the Owl Light (our 24 page print publication) is a measured voice, albeit a wider voice than many rurally based publications. This comment, and recent political hyperbole, got me thinking about how our principles are formed, and what it takes to break established patterns that can limit our world views.

I grew up in Brooktondale, NY, a small, rural community minutes (and a world away) from Cornell University. During the years of my childhood, we spent most of our time roaming the wildlands around us, which bordered on Six-Mile Creek. This was my life, my entire world. I knew nothing of politics, and it was years later, in listening to other people talk about dinnertime conversation as the norm, that I realized how void my experience was of intellectual conversation—our family simply did not talk at the dinner table. Social media was nonexistent, and the T.V. channels (obtained through an antenna mounted on our roof, which my father painstakingly adjusted as needed) offered little to expand my sphere beyond our rural enclave.

Confederate flags flew in my home town, and it was common to encounter people with guns. I took hunting season, and the killing of animals, as something that just was. My parents were, like many members of our predominantly white community, racist in subtle albeit not overt ways. There were secrets too: the interracial marriage of a cousin; the placement of my father—during the time of his parent’ divorce (unheard of then)—with caregivers on the Salamanca Reservation and the subsequent marriage between my grandfather and Rose, a woman from the tribal community. Everything was hush, hush. We were kids and, as such, not a part of adult conversations. My parents rarely thought it important to alert us to culturally crucial moments, by calling us in from our wanderings.

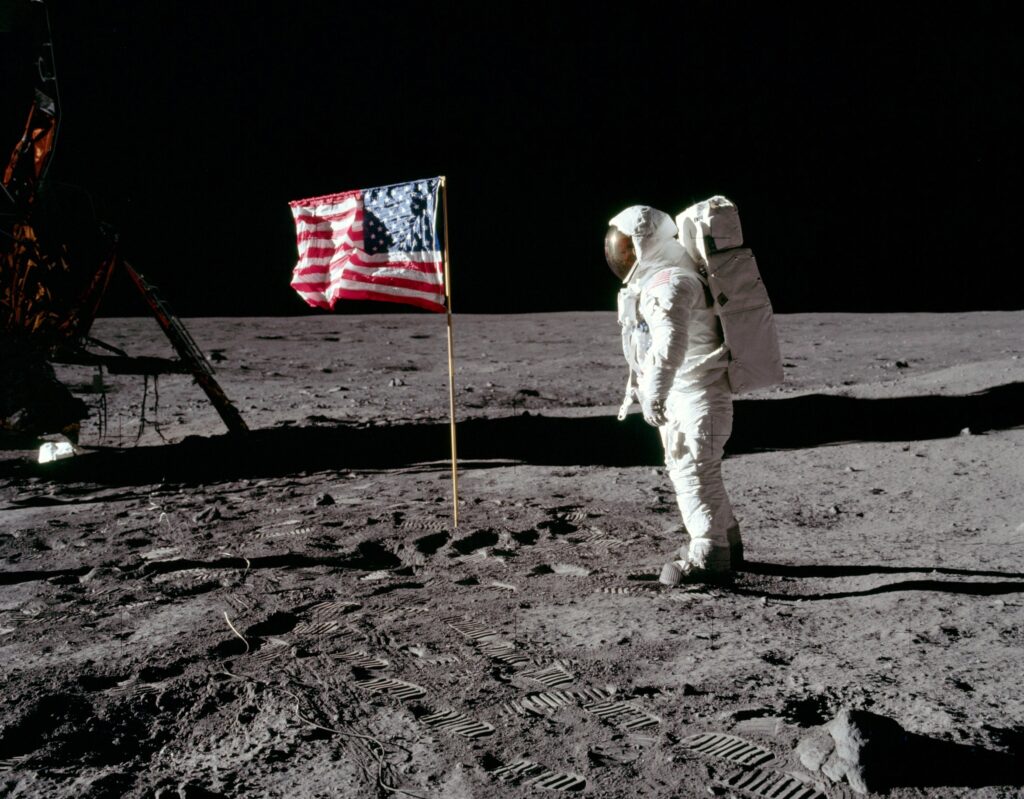

I do recall one exception: when my father called us in to watch televised coverage of the moon landing, July 20, 1969. I was seven years old and thrilled to see this. My father had instilled in me a sense of curiosity about the night sky, as he spotted and pointed out the planets and the earliest manmade satellites circling us. Now visible in the thousands, these satellites crowd our planet’s thermosphere and exosphere. (According to the Union of Concerned Scientists (UCS), there were a total of 2,666 satellites in Space as of April 1, 2020). They also give us unprecedented coverage of a huge host of events. The sheer volume of information can result in our watching a single (inevitably biased) media source or “following” those who offer high entertainment value or can shout the loudest over their opponents, even if they are saying nothing at all. We now have at our disposal a dizzying array of options for experiencing the world beyond of borders and across our shores —as a nation we have never been more divided.

Still, deep down, we all want the same things. We all do our best to meet our own personal needs and the needs of our dependents. We want happiness and love. And a little something more. My parents were good, working class people—my father was a one-handed auto mechanic; my mother a waitress— who fed and clothed us. College was never mentioned as a potential part of future plans (marriage was). Perhaps it was the curiosity instilled by my father. Perhaps it was something innate that some of us just have, that inspires us to move beyond what is our stated destiny. I ran away at seventeen and started attending a community college. This expansion of my world was invigorating, and led me to higher education and a career as a teacher. It gave me a chance to experience urban areas, and museums, for the first time. As an adult, I could never imagine living anywhere other than in a rural area. I love this life. Cities are, to me, exciting cultural escapes, but not where I might want to live. Perhaps, when all is said and done, what most changed me was not so much the education (although that certainly changed my life in many ways, including economically) but rather the hardships endured and good role models that allowed me to develop an empathy toward others. My parents were caring people, and they showed this by helping anyone in need, no matter what group they belonged to.

Nonetheless, there is no escaping the past. I thought of this as the various contributions rolled in for this issue of Owl Light News. Many touch on the historic accomplishments and great failings of America. I felt a deep, overwhelming sadness as I read these. They served not only as a reminder of lessons I had taught my students – in which I deliberately tried to frame history from multiple perspectives; from the voices of the oppressed as well as the oppressors—but also as a reminder of my own experiences with differences and bigotry. Although my challenges offer parallels to individuals from other oppressed groups, I recognize that they only represent one experience…mine. That small-town past is still very much a part of who I am, and it influences everything I do—including my decision to focus on the rural experience in Owl Light News.

Likewise, there is no escaping the past that has defined, and continues to define, our country. Much of that past—founded in the immigrant experiences of our ancestors—has allowed us the freedoms we now enjoy. I am not a believer in rewriting history—the past MUST be remembered if we are to move forward toward change. Yet there must be a constant layering of new learnings. Monuments and incomplete histories—that celebrate rather than condemn the wrongs that have been done—are hurtful reminders. Leaving them as is can legitimize the wrongs.

I just watched The Trial of the Chicago 7, a dramatized retelling of the 1969 trial of seven protestors, arrested on various charges surrounding the uprising at the 1968 Democratic National Convention in Chicago, Illinois. I contrasted this with the moon landing of the same year. In considering how that single human accomplishment offered a moment of global unity—in the midst of the racial and ideological divide of the 1960s—I was reminded that anything is possible.

We have changed as a nation, as a world; so much progress has taken place in the last fifty years alone. But there is still so much more work to be done. Given the challenges we are all facing right now, it is understandable that emotions are running high. It is understandable that our measured voices may expand as we speak up for what we believe to be just, and right. This is a good thing.

D.E. Bentley

Editor, Owl Light News