Where Did That Snake Come From?

The History of a Story

- By STEPHEN LEWANDOWSKI-

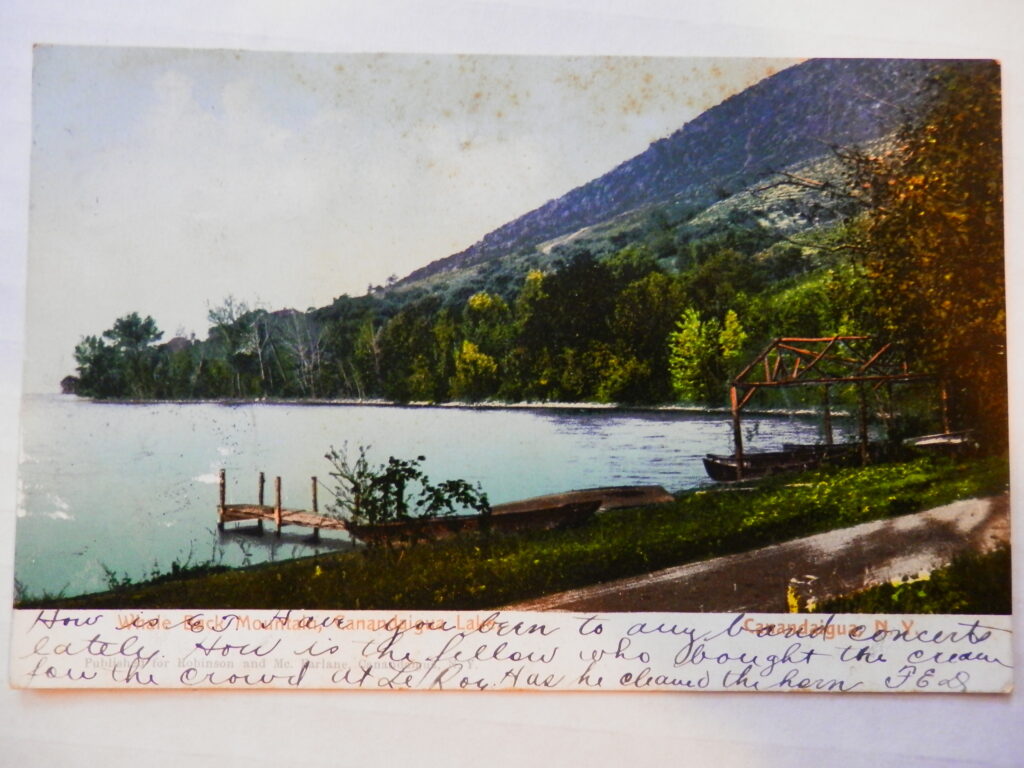

Among current residents of Yates and Ontario Counties in the Finger Lakes region of New York State, there is strong value, interest, and concern associated with the past, present and future of several hills close to Canandaigua Lake. People have been told that the previous residents, the Onundawaga (Seneca) people, had a special relationship with Bare and South Hills; that they considered the area to be their place of origin; and that a Seneca myth or legend was located on these hills.

Location

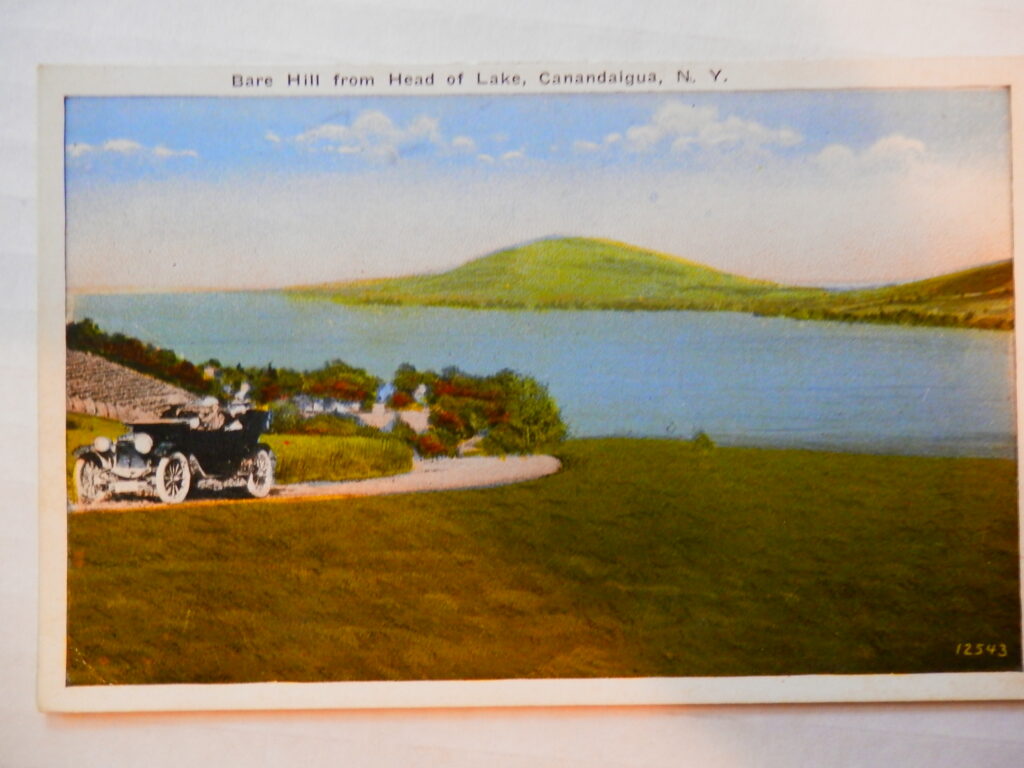

Bare Hill is located about 15 miles west of the geographical center of the Finger Lakes region, 9.5 miles south of the City of Canandaigua and 37.5 miles south of the shore of Lake Ontario. Bare Hill is 9 miles south of State Routes 5 & 20, which follow an ancient east-west trail as well as marking a general division between the Ontario Lake Plain and the Allegheny Uplands.

Bare Hill is located 5.5 miles north of the southern end of Canandaigua Lake and 9.5 from the northern end. It is in the northeastern corner of the Town of Middlesex, Yates County. At 42 ° 44’ 50” N and 77 °17’ 45” W, Bare Hill is one of the northernmost extensions of the Allegheny Plateau.

By local landmarks, Bare Hill is directly across Canandaigua Lake from Seneca Point, site of settler Gamaliel Wilder’s 1791 gristmill and distillery; 1.5 miles west of Overacker’s Corner’s schoolhouse and graveyard; a mile north and west of the ancient settlement of Vine Valley; and 3 miles north and west of the hamlet of Middlesex.

Dimensions

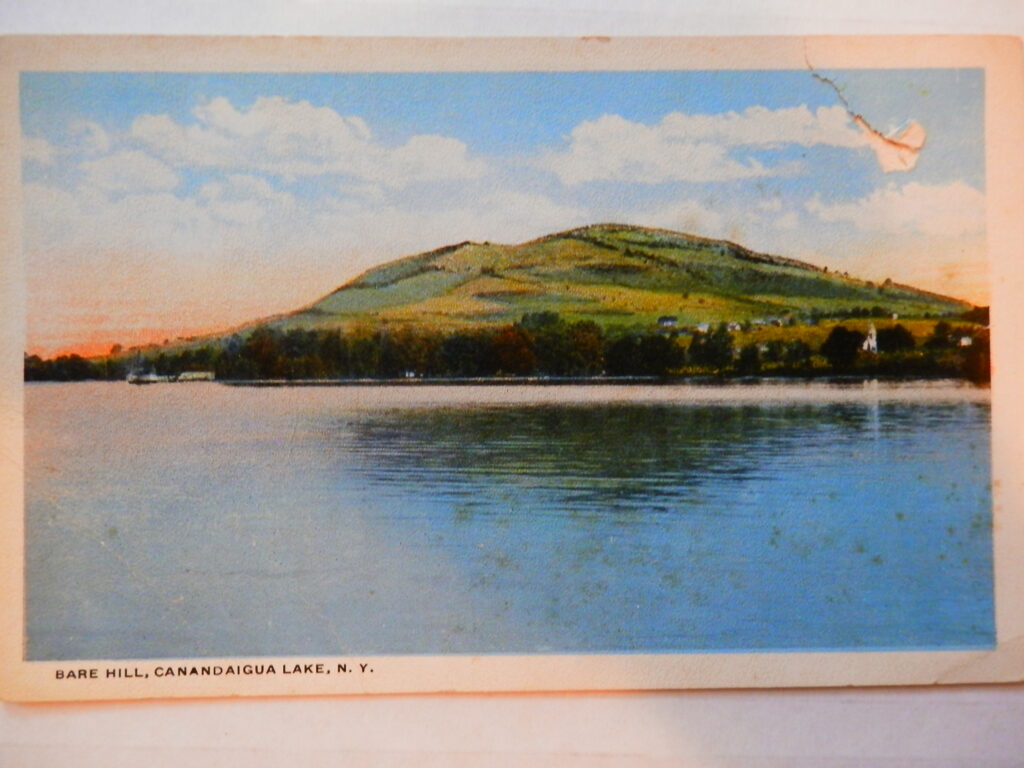

Bare Hill covers more than a thousand acres and reaches a summit half a mile east of the lake at 1540 feet above sea level, more than 850 feet above lake level.

Its neighbor hill to the south is 340 feet taller than Bare Hill at 1883 feet above sea level, but its summit is flattened and elongated. Bare Hill, by contrast, seems pointed.

Seen from above, Bare Hill is egg-shaped, smoothed and flattened like a drumlin on the northern, lead edge by glaciation. Its northern slope is the flattest, with less than a 4% rise, and approaching from the north one would be unaware of the hill. Its western slope toward the lake is the steepest, at more than 30% grade. The hill measures a mile east-west and nearly two miles north-south.

The steep slope continues into the lake which reaches a depth of 242 feet within half a mile. Beneath the sediments forming the lake’s current bed, bedrock continues to fall away another 300 feet. In other words, a bedrock hill nearly twice the size of the visible one is hidden, buried in sediment and covered with lake water.

Views

Photo by Stephen Lewandowski.

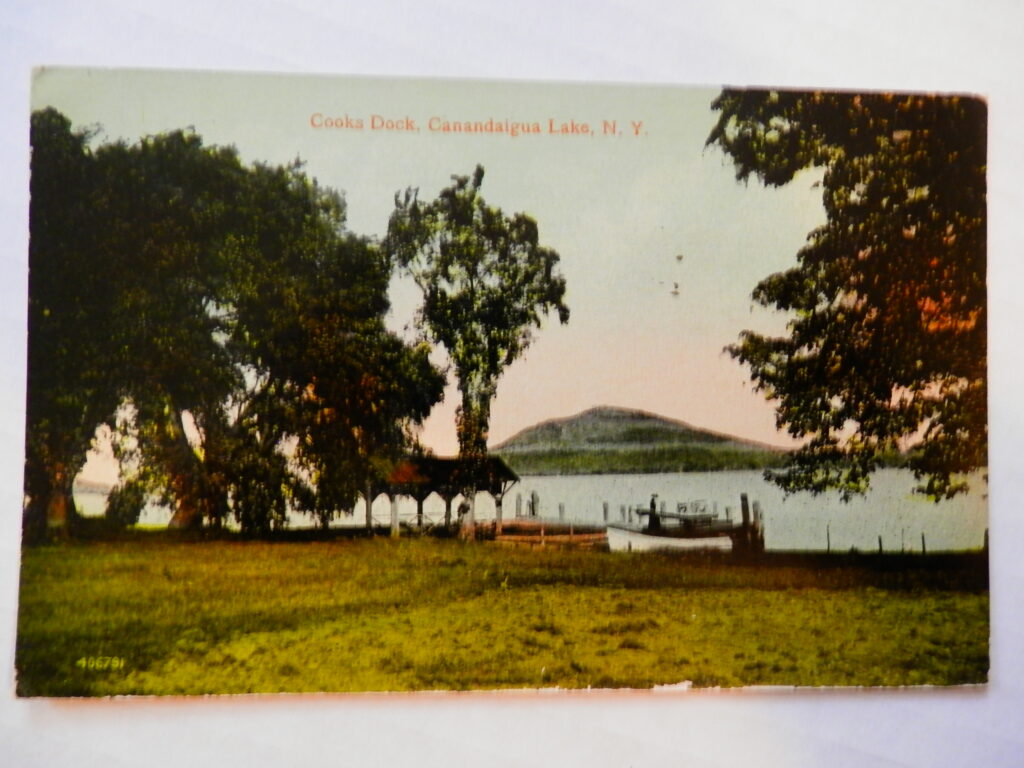

Bare Hill’s prominent location means that it is both in many views of the area and has an unusually fine view of the area.

From the northern end of Canandaigua Lake, Bare Hill is visible from the Owasco (C.E. 1000-1350) period village sites at the Deer and Sackett Farms and the Iroquois (C.E. 1350-1730) period village site at Canandaigua Fort. Both are set on rises to the west and somewhat above the present site of the City of Canandaigua. Because of the curve of the lake, one must either come to the lakeshore or climb one of the rises north or west of the city to see Bare Hill.

The most spectacular view of Bare Hill is from the west across the lake. Your eye may be caught by the diversity of landscape figures, the pointed shape of Bare Hill, the steepness of slopes, the sheltered aspect of Vine Valley, and the huge multi-colored plane of the lake below.

The view from Bare Hill is magnificent and provides a sense of the territory defined by the hill. You feel that you look down at much of the world from Bare Hill. The view is relatively unobstructed to the northeast, north and southwest for ten to twenty-five miles. The northern view is particularly striking since you are looking out over the flat lake plain with its abrupt drumlin rises far off. From the west side of the hill, looking southwest, the view is down the Canandaigua Lake valley as far as the glacial terminal moraine between Naples and North Cohocton, some 14 miles distant. Above the moraine you see the bulky “shoulders” of glaciated Hatch Hill, Pine Hill, High Point and other unnamed hills of the Cohocton River watershed.

The Story and Its Translations

Over time, a story reported to be of Native American origin has become associated with Bare Hill.

There are two original English-language sources for the Big Snake on Bare Hill story from the first quarter of the nineteenth century. The story is in the original edition of James Seaver’s A Narrative of the Life of Mrs. Mary Jemison, “taken carefully from her own words, November 29, 1823” and published by J. D. Bemis and Company of Canandaigua in 1824.

The story itself, however, is not included in the main body of the text, which is purportedly a transcription of Mary Jemison’s statements. The story is the third section of the Appendix, which Seaver’s introduction informs us “is principally taken from the words of Mrs. Jemison’s statement. Those parts which were not derived from her, are deserving equal credit, having been obtained from authentic sources.”

The story, as it appears in the Appendix, seems to be ascribed to Horatio Jones, who was, like Mary Jemison (1743-1833), a long-term captive of the Seneca. Later, he often functioned as an interpreter and still later as an agent in the payment of annuities to the Seneca. He was trusted as one faithful to language and good relations.

In A Narrative of the Life of Mrs. Mary Jemison, the story appears this way:

“TRADITION OF THE ORIGIN OF THE SENECA NATION. THEIR PRESERVATION FROM UTTER EXTINCTION. THE MEANS BY WHICH THE PEOPLE WHO PRECEDED THE SENECA WERE DESTROYED – AND THE CAUSE OF THE DIFFERENT INDIAN LANGUAGES.

The tradition of the Seneca Indians, in regard to their origin, as we are assured by Capt. Horatio Jones, who was a prisoner five years amongst them, and for many years since has been an interpreter, and agent for the payment of annuities, is that they broke out of the earth from a large mountain at the head of Canandaigua Lake, and that mountain they still venerate as the place of their birth; thence they derive their name, “Ge-nun-de-wah,” or Great Hill, and are called “The Great Hill People,” which is the true definition of the word Seneca.

The great hill at the head of Canandaigua lake, from whence they sprung, is called Genundewah, and has for along time past been the place where the Indians of that nation have met in council, to hold great talks, and to offer up prayers to the Great Spirit, on account of its having been their birth place; and also in consequence of the destruction of a serpent at that place, in ancient time, in a most miraculous manner, which threatened the destruction of the whole of the Senecas, and barely spared enough to commence replenishing the earth.

The Indians say, says Capt. Jones, that the fort on the big hill, or Genundewah, near the head of Canandaigua lake, was surrounded by a monstrous serpent, whose head and tail came together at the gate. A long time it lay there, confounding the people with its breath. At length they attempted to make their escape, some with their hommany-blocks, and others with different implements of household furniture; and in marching out of the fort walked down the throat of the serpent. Two orphan children, who had escaped this general destruction by being left some time before on the outside of the fort, were informed by an oracle of the means by which they could get rid of their formidable enemy- which was, to take a small bow and a poisoned arrow, made of a kind of willow, and with that shoot the serpent under its scales. This they did, and the arrow proved effectual; for on its penetrating the skin, the serpent became sick, and extending itself rolled down the hill, destroying all the timber that was in its way, disgorging itself and breaking wind greatly as it went. At every motion, a human head was discharged, and rolled down the hill into the lake, where they lie at this day, having the hardness and appearance of stones.

To this day the Indians visit that sacred place, to mourn the loss of their friends, and to celebrate some rites that are peculiar to themselves. To the knowledge of white people there has been no timber on the great hill since it was first discovered by them, though it lay apparently in a state of nature for a great number of years, without cultivation. Stones in the shape of Indians’ heads may be seen lying in the lake in great plenty, which are said to be the same that were deposited there at the death of the serpent.

The Senecas have a tradition, that previous to, and for some time after, their origin at Genundewah, this country, especially about the lakes, was thickly inhabited by a race of civil, enterprizing and industrious people, who were totally destroyed by the great serpent, that afterwards surrounded the great hill fort, with the assistance of others of the same species; and that they (the Senecas) went into possession of the improvements that were left.

In those days the Indians throughout the whole country, as the Senecas say, spoke one language; but having become considerably numerous, the before mentioned great serpent, by an unknown influence, confounded their language, so that they could not understand each other; which was the cause of their division into nations, as the Mohawks, Oneidas, &c. At that time, however, the Senecas retained their original language, and continued to occupy their mother hill, on which they fortified themselves against their enemies, and lived peaceably, till having offended the serpent, they were cut off as before stated.”

David Cusick’s Version

In 1827, David Cusick’s Sketches of Ancient History of the Six Nations was privately printed at Lewiston, NY. In 1828, a second edition of 7000 copies was published at Lewiston. In 1848, it was re-published by Turner and McCollum Printers of Lockport, NY. The second and third editions contain four woodcut illustrations and several extra paragraphs of text, and in the text it is stated that the sketches were written “from the Tuscarora Village, June 10, 1825”.

Cusick was an educated Tuscarora (the sixth of the Six Nations, who joined the five original League members after moving from North Carolina in 1712). Cusick included this version of “The Serpent at Bare Hill” in Section III of his sketches, Origin of the Kingdom of the Five Nations, which was called A Long House:

“There was a woman and son who resided near the fort, which was situated near a nole, which was Jenneatowaka, the original seat of the Te-hoo-nea-nyo-hent (Senecas) the boy one day, while amusing in the bush he caught a small serpent called Kaistowanea, with two heads, and brings it to his apartment; the serpent was first placed in a small warm box to keep tame, which was fed with birds, flesh, etc. After ten winters the serpent became considerable large and rested on the beams within the hut, and the warrior was obliged to hunt deers and bears to feed the monster; but after awhile the serpent was able to maintain itself on various game; it left the hut and resided on top of a nole; the serpent frequently visited the lake, and after thirty years it was prodigious size, which in a short time inspired with an evil mind against the people, and in the night the warrior experienced the serpent was brooding some mischief, and was about to destroy the people of the fort; when the warrior was acquainted of the danger he was dismayed and soon moved to other fort; at daylight the serpent descended from the heights with the most tremendous noise of the trees, which were trampled down in such a force that the trees were uprooted, and the serpent immediately surrounded the gate; the people were taken improvidentially and brought to confusion; finding themselves circled by the monstrous serpent, some of them endeavored to pass out at the gate, and others attempted to climb over the serpent, but were unable; the people remained in this situation for several days; the warriors had made oppositions to dispel the monster, but were fruitless, and the people were distressed of their confinement, and found no other method than to rush out at the gate, but the people were devoured, except a young warrior and his sister, which detained, and were only left exposed to the monster, and were restrained without hope of getting released; at length the warrior received advice from a dream, and he adorned his arms with the hairs of his sister, which he succeeded by shooting at the heart, and the serpent was mortally wounded, which hastened to retire from the fort and retreated to the lake in order to gain relief; the serpent dashed on the face of the water furiously in the time of agony; at last it vomited the substance which it had eaten and then sunk to the deep and expired. The people of the fort did not receive any assistance from their neighboring forts as the serpent was too powerful to be resisted. After the fort was demolished the Council fire was removed to other fort called Than-gwe-took, which was situated west of now Geneva Lake.”

A later study (1987) of Cusick’s work by Russell Judkins pronounces it “an early example of Iroquois intellectual endeavor in ethnic self-analysis and the communication of Native American culture.” Judkins argues that in its structure and language the work “ultimately reflects Iroquoian mind, spirit, assumption, and reality” and finds great value in Cusick’s use of “symbolic imagery” and “language which ‘bridges’ two cultural worlds.”

The Snake

Wallace Chafe’s Handbook of Seneca Language (1963) translates Kashaistowaneh” as “Big Snake.” In one version, it is gigantic and has two heads, and in the other it is simply gigantic. Each of the stories acknowledges that there’s more to the hilltop than meets the eye. One version says the Seneca “broke out of the earth” and the other that they “originated from the top.”

What about the snake? Neither story says so, but could the snake have come from the same hole? Mary Jemison’s version doesn’t mention an origin, and Cusick says the snake was found in the bush. Why did it follow them? To destroy them and give them a fresh start? The snake links an under and other world with the present and above ground world.

Since the story originated in the Seneca society and language, what do snakes mean to them? One prominent past association of snakes was with water. Almost any spring, well or seep was thought to have a snake, like a guardian spirit, lurking nearby. In a number of Seneca tales, lakes are inhabited by huge snakes whose intentions toward humans seem to be malevolent. The snakes can take human form, the better to mate with human women, but are in constant conflict with He-no the Thunderer, a god associated with another form of water, rainfall from the sky.

If Big Snake is like other snakes from around the world, his reputation is mixed. He lives at the boundary between the world we know and the ones we don’t. What’s hidden underground is akin to what’s hidden in times past and by death. Big Snake lives near chaos and brings destruction with him, yet he also bears a strong relation to procreation, birth, rainfall and fertility. He is a go-between, with powers to destroy and create. Despite the good qualities such as generosity and protection of the weak demonstrated by the orphan in caring for the snake, the boy made a fundamental error: such things make poor pets.

Other Variants

References to and variants of the tale are included in Henry R. Schoolcraft’s Notes on the Iroquois (1846), Harriet Maxwell Converse’s Myths and Legends of the New York State Iroquois (1908), William Beauchamp’s A History of the New York Iroquois (1905) and Iroquois Folk Lore (1922), Arthur Parker’s Seneca Myths and Folk Tales (1923), and Joseph Bruchac’s Iroquois Stories (1985).

Schoolcraft appropriates Cusick’s materials, including the Big Snake story, with only minimal attribution of authorship. No mention is made of David Cusick when the story appears on pp. 60-1 of Notes…. Later in Notes… (pp. 237-40), a letter from Reverend James Cusick, David’s brother, seems to convey the remainder of Cusick’s Sketches… to Schoolcraft’s use with brother David’s authorship relegated to a footnote.

The Converse version is a literary re-telling of David Cusick’s story. It appears in Part 2 of her volume as material which had not been prepared for publication at the time of her death in 1903 but was “Revised by the Editor (Arthur Parker) from Rough Drafts Found Among Mrs. Converse’s Manuscripts.” Her snake, like Cusick’s, has two heads and her additions to the tale are identifying the hero whom Jemison calls “an orphan” as Ha-Ja-Noh, a boy who became a warrior, and in emphasizing the hypnotic power of the snake’s “swaying heads” and “bright eyes.” In Cusick’s version of the tale, the boy is not called an orphan.

In History…, Beauchamp recites the Big Snake on Bare hill story and ascribes it to “a general Seneca tradition” while offering as a possible “explanation” that “the fort was besieged by a powerful foe, or that something near by produced a pestilence.” He does call the story a “favorite” Iroquois tale and notes that “the story seems to belong to but one of the two great bands of the Senecas.” In Folklore… Beauchamp republishes both Cusick’s and Jemison’s versions. He comments that he was told a version similar to Jemison’s by Captain Samuel George, an Onondaga.

Arthur Parker includes the theme in his Literary Elements of Seneca Folklore as “Number 43: Fast-growing Snake. A boy finds a pretty snake ands feeds it. It grows enormously and soon eats a deer. Game is exhausted and snake goes after human beings.”

Joseph Bruchac follows the Converse version in most details.

Some Other Themes

Neither Jemison nor Cusick attribute rapid growth to the snake. Cusick states that it took ten winters for the snake to leave the lodge and thirty years to reach a dangerous size. The snake’s rapid growth first appears in Converse’s version and is reaffirmed by Parker.

Jemison calls the brother and sister “orphans” but Cusick does not. Neglected orphans are as ubiquitous in Iroquois folklore as wandering princes are in Grimm. Jemison doesn’t refer to the boy as a warrior, but Cusick does, and Converse not only makes him a warrior but gives him a name, Ha-ja-noh.

The weapons and their origin also vary among versions. Jemison says that an oracle advises the boy to make a “small bow and poisoned arrow, made of a kind of willow” and to shoot it “under the scales.” Cusick says that a dream advised the boy to “adorn his arms with the hairs of his sister, which he succeeded in shooting at the heart.” Finally, Converse says a dream instructed the boy to make “arrows of dark snake wood” tipped with “white flint” and bow strung “with a lock of your sister’s hair” and aimed at the monster’s heart.

The Seneca consider dreams oracular, so there is probably no conflict in those terms. The snake wood and white flint of Converse seem unduly romantic. In all versions, the weapon which is small (unlike its opponent) and made from a kind of willow, draws some magic power from association with the sister’s hair, and penetrates the creature’s scales to its heart, unlike the failed conventional weapons of other warriors who were devoured by the snake.

Arthur Parker

Arthur Parker (1881-1955) was a protégé of Mrs. Harriet Maxwell Converse (1836-1903). In his youth, he seems to have followed her more fanciful versions and interpretations of Seneca folklore. Mrs. Converse was a valued friend of the Iroquois in that she opened her New York City home to Native American visitors, spent her fortune in relieving the distress of their indigents, and actively lobbied in Albany and through the New York City press for their protection and benefit.

In his later years, however, Parker returned to study of Seneca folklore with a fresh perspective and influenced by the science of anthropology. Parker had returned from his position as State Archaeologist in Albany to become director of the Rochester Museum of Science. Working in Rochester and living in Naples, he lived and worked in the landscapes depicted in the stories he retold and studied.

In 1949, Parker was interviewed by the Canandaigua Daily Messenger and asked specifically about the hills and the snake story. His opinion at that time was that Bare Hill is Genundewah and should be associated with the snake story, but that Nundawao, the hill from which the Seneca say they originated, is the next hill south along Canandaigua Lake locally known as South Hill. It is not difficult to imagine the original Seneca people issuing from the chasm called Clark Gully in the southeast slope of that hill.

Allegory?

Professor Laurence Hauptman’s The Tonawanda Seneca’s Heroic Battle Against Removal (Albany: SUNY Press, 2011) provides us with some clues as to why this story reached prominence in the 1820s and 30s. The book’s cover illustration is one of Ernest Smith’s (1907-1975) WPA watercolors showing a huge rattlesnake just pierced by a small arrow from the bow of the boy and his sister.

Tonawanda leader Corbett Sundown was quoted in 1987 as saying that the Big Snake is a “white man’s story.” Its most obvious interpretation is that Native Americans fed and protected weak colonists when they first appeared on this continent and then were “devoured” when the colonies grew large and strong.

Perhaps Sundown means that the story is about white men, not by/for white men. Evidence for this view is provided by Hauptman: he relates that the Big Snake story was told by Tonawanda sachem John Blacksmith in 1838 to proto-anthropologist Henry Rowe Schoolcraft as a description of fraudulent activities of the Ogden Land Company devouring the remaining reservation lands of the Seneca, forcing them to re-locate to Indian Territory in Kansas. Blacksmith labored the rest of his life along with Eli Parker and attorney John Martindale to regain the Seneca land. Only in 1857 were the Tonawanda Seneca (who refused to remove) allowed to sell their Kansas reservation lands and use the proceeds to buy back most of their reservation in New York State.

Questions Remain

Questions adhere to the story and the hills. Is the Big Hill in question Bare Hill or South Hill? Was the story native in origin or, as Tonawanda Seneca leader Corbett Sundown said in 1987, “a white man’s tale”? Its most obvious interpretation is that Native Americans fed and protected weak colonists when they first appeared and then were “devoured” when the colonies grew huge and strong. Is there more to the tale? Is there archaeological evidence of the village that several texts describe on top of either hill?

One hundred and ninety years later, there are no new texts to which to appeal for answers. There may, however, be remnants of the story being told in the Seneca language. If so, these and other questions might receive an answer in Seneca.

***

Bare Hill is protected from development since 1988 as part of the NYS Hi Tor Wildlife Management Area (Hi Tor translates into high hill). Saturday 8:30pm of Labor Day weekend, there’s big fire and dancing on top.

Steve Lewandowski was born in Canandaigua. He has published widely in journals such as Rolling Stone, Country Journal, The Northern Forest Forum, and Hanging Loose. He has fourteen books of poetry and essays from a variety of literary publishers. His fifteenth, Hard Work in Low Places, will be published at the end of this year by Tigers Bark Press of Rochester.