Roll Call

- By BARBARA JORDAN –

The Ancient Allure of Marbles

I bought my first jar of marbles over twenty years ago, at A to Z Antiques in Hemlock, and a love affair began. I already admired antique glass buttons and Art Deco costume jewelry for their beautiful art glass. Marbles opened yet another avenue of appreciation, except that marbles are in some ways more complex, in that to understand them, it’s useful to learn something about glass itself.

Glass marbles are truly little jewels. The glass can be transparent or opaque, opalescent, or contain uranium so it fluoresces — uranium glass indicates a pre-WWII marble. (If you have some old marbles, shine a blacklight on them, you may be surprised!) Coppers and ground semi-precious stones, flecks of mica, even gold and silver, can be added to glass. Hand gathered “Lutz” marbles have shimmering goldstone bands, and machine-made marbles with” oxblood” or “aventurine” ribbons are prized by collectors. “Paperweight” marbles are dollhouse replicas of the real thing, and “sulphides” have tiny figures inside.

The mystery of glass was known by the Second Millennium B.C. in Egypt, Mesopotamia, Syria, and the Indus Valley. It was mainly molded into beads and shapes. The Romans discovered glass blowing and added new techniques to the art. We know Roman children used marbles in a game they called “nuts” —this is mentioned by Ovid and others—although no one thought to tell us the rules. There’s a set in the British Museum that are speckled, like dice.

The recipes for glass were, and still are, closely guarded by chemists. In the Middle Ages, when glassmaking blossomed on the islands around Venice, the artisans were held in such esteem that their children could marry into the nobility. Murano was one of those islands. As well as Murano glass, the Venetians invented a number of exclusive types: milk glass, millefiori, goldstone (copper specks added to translucent glass), and a striped or spiraled filigree glass made by embedding colored glass canes inside clear. Recipes for lead and crystal have their origin there. The Italians also advanced mirror-making and fashioned prized chandeliers.

On the other hand, if a glassmaker left his city without permission—or worse, divulged glass secrets, thus jeopardizing Venetian ascendency—the penalty was death. There were Venetian spies and assassins for just this purpose.

The sixteenth century was the Golden Age of Venetian glass. Then an Englishman, George Ravenscroft, perfected leaded glass and crystal and the trade shifted to England. Meanwhile, both Bohemia and Germany became vibrant glass-making centers, producing drinking vessels, flasks, and bottles for the aristocracy, then beads, ornaments, and less expensive ware. A lot of cross fertilization of glass ideas and techniques occurred during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, as well as exports and imports. There was also vigorous trade in semi-precious stones. Stone and earthenware marbles were still used by children everywhere — before and even after German glass marbles come to America in the 1860s.

In fact, back in the day most marbles in America came from Germany, whether of glass, clay, or stone: the three main divisions of marbles. Stone marbles were usually made of agate, a kind of quartz which changed color if heated or dyed. Early ones were hand made, requiring workers to lie all day on their stomachs grinding the marbles against a millstone powered by a water wheel. Later the stones were tumbled, and might include malachite, tiger’s eye, amethyst, carnelians, etc. “Bullseye banded agates” were popular from the 1880s through WWI.

Similarly, Victorian boys and girls played with earthenware marbles. You can easily find the low-fired plain clays in antique stores: they’re too common to have much value. Some have colors because they were dyed after firing — which is different from a glaze, which is applied to the clay before it is fired. Benningtons, a popular glazed earthenware marble, are therefore a step up in value. They’re commonly found in brown or blue, and have round surface pits (where they touched in the kiln) that look just like craters on the moon. The less common green and the multicolor “fancy” Benningtons are worth more; pink is the rarest, and able to fetch $50 and up, depending upon size.

A half-inch or three-quarter inch brown or blue Bennington sells for a dollar or two, but a two-inch Bennington would sell for $30. That pricing would apply to “Chinas” as well. Chinas are made of porcelain, a smoother clay that fires at a higher temperature. Chinas were popular during the same time period. Some are plain white, while others are stenciled, or hand painted — with bands, spirals, leaf-sprays, flowers, and the like. But when German hand-gathered marbles appeared in the second half of the nineteenth cen-tury, the subdued stones and clays were outshone. Germans were, and are, a bewildering candy store of colors, and they cover a breathtaking variety of styles. All glass marbles fall into one of five types: corkscrews (unique to Akro Agate), swirls, slags, cat’s eyes, and solid. They range in size from peewee to over two inches in diameter.

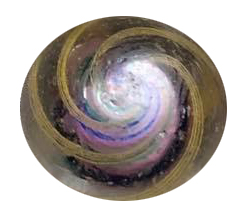

German swirls are one of the most coveted. They were individually made marbles, and the process was long and repetitive, depending upon the number of colors used and the complexity of the design. “Solid Cores” and “Divided Cores” are two kinds of elaborate swirls which required several steps by the glass maker. The craftsman dipped a five-foot-long iron rod, called a “punty,” into a pot of molten glass. Then, letting the glass cool slightly, he’d repeat the process until he had a “gob” of glass gathered (hence “hand gathered”) on the end of the punty, and then he’d roll it on a marble surface until he’d fashioned a cylinder about six inches long. When the heat was right, this glass gob would be rolled over a series of very thin glass rods which another worker had already placed side by side in grooves in a metal pan. The placement and number of these thin cylinders, and any spaces left open between them, determined the type of “core” in the marble — which might look like a netting or lattice (“Latticinio” core), or like a peppermint striped barber pole. Thus, these thin glass rods became the marble’s center, as the original gob gathered and enveloped them. A lot of twisting, pulling, lengthening and reheating had yet to occur before a finished glass cane was finally ready to be cut into individual marbles.

German glass marbles weren’t produced in large numbers until the mid-nineteenth century, after the invention of the marble scissors, which sheared each marble separately and left a pontil mark.

(The shears had been designed originally to smoothly cut glass eyes for dolls and toy animals.) A pontil mark always indicates a hand gathered marble.

Latticinio cores are the most common German swirl marbles. Others might have cores that are striped like candy canes, or like multi-colored bands. In addition, the outer surface of the marble can be plain, or have stripes or bands of different widths, Coreless swirls have only these outer swirls or bands. Joseph’s Coat, Lutz, and Indians are examples of banded core-less marbles.

There are many German coreless swirls where the glass mixture determines their appearance. This is the case with Onionskins, End-of-Days, Micas, Submarines, and Mists, to name a few. One German type worth mentioning is called a Sulphide, which is neither a swirl nor a solid marble, but in a class of its own. Sulphides are clear glass marbles with tiny figures inside — animals, birds, people, angels, crucifixes, numbers — objects as varied as the prizes in plastic capsules kids could buy in machines outside grocery stores. Rare Sulphides can fetch $5,000, or more!

I did find a few German hand-gathered marbles in my original jars, but they were always well-played — with chips and flea bites. Like any other collectible, condition matters. And as mentioned, size matters too: the bigger the marble, the better. Some large, perfect German marbles can be worth thousands of dollars, although most nice ones of about a half inch sell for $15 to $30, and if you double that size, they start around $50.

In my early days of marble collecting, I saw pontils everywhere. One vendor at A to Z Antiques had over a dozen jars for sale, and over the course of a year I bought them all. As soon as I’d get home, I’d sort my marbles — mostly by color, putting any unusual ones off to the side. Then I’d search on Ebay to try and identify what I had. I quickly learned the antique Germans were valuable, and that their pontils could be of various kinds — melted, pinched, creased, ground, or regular pontils.

What I didn’t know was that machine-made marbles often had marks that resembled pontils in their manufacture — creases, folds and “cold rolls” —because they, too, had seams where they’d been cut. Being able to “see” the seams in a marble may be a later step in the learning curve, at least that’s been the case for me; however, soon I began to recognize a few marble makers from the color and pattern on the marble.

Of course, there are some marbles, called “Transitionals,” that bridge the gap between hand-gathered and machine made. They blended techniques, and some have pontils: Leighton and Navarre are one kind of transitional marble with pontils, and hand-gathered slag marbles (one-stream early marbles) may or may not. The slags produced by the M. F. Christensen Company are collectible, and easily recognized by a swirl pattern that resembles the number nine at the end of a long tail. Akro Agate and Peltier Glass Company also made early slag marbles.

Some contend that the most beautiful glass marbles were made by the Christensen Agate Company (not to be confused with M. F. Christensen & Sons), whose marbles are affectionately called CACs. It was founded in Ohio in 1925 and had stopped production by 1931. Their colors are vibrant reds, blues, oranges, yellows and greens, with some so exceptionally bright they were called “electric.” Their marbles are highly collectible. Some of their slags, striped opaques, and transparents are affordable, but many CAC swirls and “Flames” (five or more ribbons ending in points like flame tips) command more money—especially if in mint condition. The rarest CACs are the famous “Guinea” marbles (named after the hens in the factory yard) which can sell for $200 to $1,000, depending upon design, and of course condition.

Many of their best glass recipes came from a German glass maker, Arnold Fiedler, who left them to work for the Akro Agate Company. Akro Agate Company began when two enterpricing partners decided to buy bulk quantities of popular marbles, repackage them in small bags, and add an Akro logo. This had never been done before. Marbles were sold in bulk, or like penny candies: you chose a few, or bought a small bag. But there was no name recognition. Akro changed that by using colorful labels and boxes and enticing children through advertising. They were wildly successful, and within a few years Christensen Agate Company went out of business—Akro, their best customer, bought the last of their marbles.

By 1925 Akro was using its own machinery, and in 1928 Akro patented a spinning cup, whereby a stream of colored glass would be poured onto spheres of revolving opaque or transparent glass.

This technique created the famous Akro Corkscrew —which they called the “Spiral.” Corkscrews have a band (or bands) of color that swirls from pole to pole. Desirability depends upon the size and the number of colors in the corkscrew: a three-color or four-color corkscrew in an unusual color combination is, naturally, better than a two-color.

A famous Akro corkscrew is the “Popeye,” named after the Akro box which sported a picture of Popeye the Sailor. These are clear-based marbles with white filaments and an additional two-colors that “cork” (wind from pole to pole); there are also Popeye Patches, which fall into another category. Patches are two-color marbles which look like their names. Some soft colored ones are called “Moss Agates,” but there are also “Brushed Patches,” and ones that contain special glass, such as “Oxblood” or any of the “Ades.”

Oxblood is a dark red glass much prized by Akro collectors. There are Oxblood Cork-screws with special names like “Silver Oxblood” or “Eggyolk (yellow base) Oxblood” or a “Bluebood.” Similarly, there are Akro swirls called “Milky Oxbloods.” “Ades” are translucent glass corkscrews or patches with lemon, lime or cherry bands, so you get “Limeade Corkscrews” or “Lemonade Patches” as the nomenclature joins together. Akro also made “Bricks,” “Sparklers,” “Opals,” “Imperials,” “Carnelians,” and “Moonies,” to name most.

It gets complicated when certain color combinations are given special names. Peltier Glass Company, also one of the early, successful machine marble companies, surpasses Akron with names for particular marbles. One of its poplar marbles was the “Rainbo,” another was the “Peerless Patch.” Peltier’s swirls and “Rainbo” color combinations have a myriad of specific names, and, since value depends upon being able to identify what you have, learning the names is important. “Zebra,” “Ruby Bee,” “Mandarin Bee,” “John Deere,” “Bengal Tiger,” “Green Dragon,” “Superboy,” “Spiderman,” “Christmas Tree,” “Tracer” (akin to “Ades”), “Golden Rebel,” “Liberty,” and “Blue Panther” are, literally, only some Peltier color combinations.

German marbles weren’t exported after WWI. It wasn’t cost effective, and machine-made marble colors could be just as exquisite. The Golden Age of Machine Marbles occurs between the 1920s and the start of WWII and is dominated by Akro and Peltier. By the 1930s, Master Made Marbles, Ravenswood, Alley Agate, Allox, and Vitro Agate were also competing for a place in the lucrative marble market. Vitro Agate, in particular, made dozens of types of marbles, from “All Reds” to “Helmets” to “Conquerors” and more, all of which divide again into subtypes, and then, like Akro and Peltier, have names based on color combinations — “Easter Eggs,” “Parrots,” “Sweet Peas” and “Wedding Cakes” are a few.

By the 1960s, Asian marbles were being imported, most notably “cat’s eye” marbles, which are transparent base marbles with flattened ribbons inside, called “vanes,” that intersect along a center axis. Japanese cat’s eyes have little value — you can tell them by their darker, often green-tinted, glass. But cat’s eye marbles made earlier by Peltier, which look like little bananas, and hybrid cat’s eyes by Vitro Agate are becoming collectible. Today Jabo is the largest marble manufacturer is the United States, drawing collectors by producing limited edition “runs” of wonderful swirls, and then changing, and naming, new color palettes and designs every year. Vacor de Mexico is the largest marble maker in the world.

For anyone interested in collecting marbles, there are many great marble identification sites online. YouTube in particular has some excellent videos. Just use “Akro marbles identification,” or “Peltier,” or any of the other companies I’ve mentioned in your search terms, and you’ll find the main websites. I belong to several Facebook Marble Groups, and most members are generous in helping people ID marbles. Try looking at some of the websites first. Please don’t include more than a handful of marbles in a photo (or it becomes too complicated) and be sure to shift the position of the marbles and then take several additional photos so viewers can examine the marbles for all angles. Experts have to be able to see the “seams” — and as I said, being able to see the seams takes practice.

I couldn’t have imagined that that first jar of marbles would take me on such a journey, or that there was so much to learn. Usually I hunt for marbles at flea markets or yard sales, and machine mades make up most of my collection. Peltier marbles have become my favorite and, like any collector, I’d like to own examples of the more exotic ones. I’ve got Tracers, Sunsets, and some great multicolor swirls (“MCS”) such as Zebras, Ruby and Custard Bees, and even a “Ketchup and Mustard.” Like others, I often share my finds on “Marble Nuts,” the name of a Facebook group, and I keep learning.

Barbara Jordan retired from teaching poetry at the U. of Rochester. Her books are Channel (Beacon) and Trace Elements (Penguin). She now hunts flea markets for various treasures.