The Monthly Read-Not Your Average Fairy Tale

- By Mary Drake

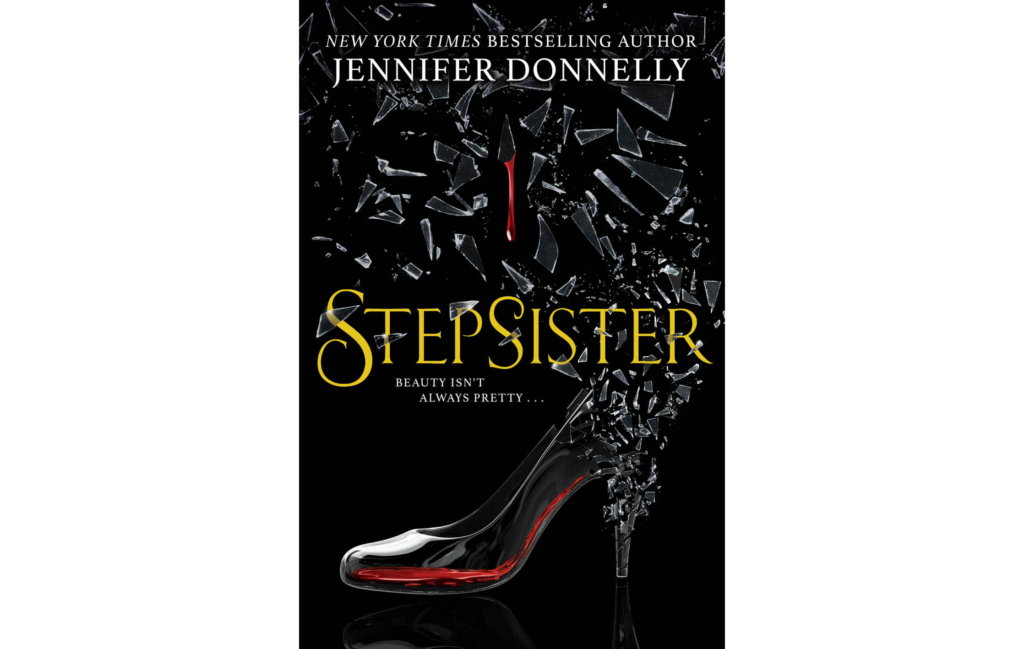

A Review of Stepsister by Jennifer Donnelly

Some stories just won’t die. They are told and retold, tweaked and changed, made into plays, movies, operas, ballets, and songs. One such story is Cinderella. In Marina Warner’s 2014 book Once Upon a Time: A Short History of Fairy Tale, she says that fairy tales are “stories that try to find the truth and give us glimpses of greater things.” In the story of Cinderella, classified as a “persecuted heroine” tale, the “greater thing” might be the eventual success of the underdog, and we would all like to believe “the truth” of poetic justice, that people ultimately get what they deserve.

But Anna Rooth in her doctoral dissertation entitled The Cinderella Cycle reckons that “The fact that over 900 versions have been written is a testament to the ‘potent’ power of this story.” Okay. But if there are so many versions in so many languages, why would Jennifer Donnelly, the author of the new book Stepsister, choose to write another book about Cinderella? And why would you want to read it?

The simple answer is because this book takes the fairy tale in a whole new direction and to a whole new level. This time it’s not about Cinderella; it’s about one of her supposedly ugly, wicked stepsisters, whose name is Isabelle, whom we’ve never heard from before. Finally, we’ll get her side of the story.

Stepsister is similar to Gregory Maguire’s 1995 book Wicked, in which the reader comes to learn about the life and times of the Wicked Witch of the West, a similarly infamous character. In Wicked, we’re told how the wicked witch grew up, what forces acted upon her to make her the way she was, and how she felt about having green skin. Stepsister does the same with Isabelle. She doesn’t have to worry about being green, but she does have to worry about how to walk after cutting off her toes to fit into the glass slipper.

The fact is, Isabelle didn’t really want to lock Cinderella in her room when the prince came visiting, and she certainly didn’t want to cut off her toes. She was just trying to please her demanding mother and save her struggling family from penury. Plus, she was trying to conform to contemporary ideas of what women should be.

Donnelly goes to great pains to paint Isabelle as an average person, with her own dreams and her own failings. As children, Isabelle, Ella, and Octavia, the other stepsister, all play together and get along famously, until someone tells Ella that she is pretty, and tells Isabelle that she is ugly. Even though she is envious of Ella and treats her cruelly, Isabelle is aware of how badly she is acting; she recognizes her shortcomings and regrets her behavior. This makes her a main character we can sympathize with.

The story begins with a Prologue in which an old crone named Fate and a dashing young nobleman named Chance are fighting over the map of Isabelle’s life. Throughout the book, these two characters, in true fairy tale fashion, keep trying to influence Isabelle’s life one way or the other. Fate, who drew the map, asserts that “Mortals do not like uncertainty. They do not like change.” She believes that we are foolish creatures who blindly follow the maps she makes of our lives. But Chance insists that, given the opportunity, humans will sometimes take risks and move beyond the limited lives Fate has mapped out for them. He cuts a dashing figure and “His eyes promised the world, and everything in it.” He regards Isabelle as a challenge and wants to “give her the chance to change the path she is on. The chance to make her own path.” Risks often present very attractive rewards, but they are also, well, risky. So Fate and Chance make a bet over the direction Isabelle’s life will take.

The story’s beginning does not bode well for Isabelle; she cuts off her toes in order to fit into the glass slipper and almost convinces the prince that she is the one he seeks but she is betrayed by a white dove who flies down from a magical tree and tells him about Isabelle’s duplicity, tells him that blood is coming from her shoe and that she is not “the one.” Ella is the one, and it is she who rides off to marry the prince and leaves Isabelle, Octavia, and her stepmother behind. They become infamous and reviled in the town of Saint-Michel where they live. (Donnelly is working from the French version of Cinderella written in 1697 by Charles Perrault.)

So what is Isabelle really like? Well, she’s definitely not like Ella. She’s not passive and sweet tempered as a seventeenth-century woman was supposed to be. As a child she was a tomboy who liked to climb trees and play at pretend sword fighting with her friend Felix. But she is thoroughly chastened by the whole glass slipper episode and decides that yes, she has treated Ella badly, and she’s going to make up for it by becoming a better person. So she decides to do good deeds and begins by taking some much-needed eggs from her family’s chickens to an orphanage filled with poor children. But it doesn’t go so well. The children have heard of her. They encircle her and chant ugly rhymes:

Stepsister, stepsister,

Mother says the devil kissed her!

Make her swallow five peach pits,

Then cut her up in little bits?

Then they begin throwing the eggs and they “pelted her with them as hard as they could.” Isabelle knows that she “should have run straight out of the courtyard and back to her cart. But Isabelle was not one to turn tail.” It is this spunk that will serve her well in the end, when she discovers an invading army bent on destroying Saint-Michel and is magically transformed into the general of her own army.

In true fairy tale fashion, she ends by taking a chance, fighting successfully, and being recognized as a national hero. Women, Donnelly seems to be saying, should not feel limited by their looks or by societal norms. Not if they’re willing to follow their heart and take a chance. The author even throws in the twist that Ella is not, in fact, perfect; she admits to having thwarted the love between Felix and Isabelle, who nevertheless come together at the end.

Jennifer Donnelly is an American author who has written many books of historical fiction as well as fairy tale fiction. Even though Stepsister is classified as a book for Young Adults, it is very well written and explores relevant topics that provide food for thought for readers of any age.