The Demon Yields ~ Duologue by Merton Bartels

For an historical condensation on chasing the Unknown Demon of breaking the sound barrier on 14 October 1947 by test pilot Chuck Yeager in a Buffalo, NY-made, Bell X-1, follow the duologue between investigator Fancy Airs and Chuck Yeager. Simply stated, any flight means to fly under control by obtaining lift through wing and fuselage design and, more often, with engines with enormous propulsion. The more optimum the design usually means the faster is the air vehicle with less drag, higher altitude capability and economy of flight. With essential flight characteristics identified, let us monitor the inquiries Miss Airs initiates.

For an historical condensation on chasing the Unknown Demon of breaking the sound barrier on 14 October 1947 by test pilot Chuck Yeager in a Buffalo, NY-made, Bell X-1, follow the duologue between investigator Fancy Airs and Chuck Yeager. Simply stated, any flight means to fly under control by obtaining lift through wing and fuselage design and, more often, with engines with enormous propulsion. The more optimum the design usually means the faster is the air vehicle with less drag, higher altitude capability and economy of flight. With essential flight characteristics identified, let us monitor the inquiries Miss Airs initiates.

Miss Airs: How does one advance from a low-altitude pilot to become the one who rode the spacecraft from subsonic to supersonic numbers? And what made you accept the challenge, General Yeager?

Chuck Yeager (CY): May I call you just Fancy? I assume you’ll agree to that. I am sure many books will be written and movies made of the effort to break the sound barrier. Two human qualities a pilot must have to achieve the seemingly unobtainable; and these are exceptional decision-making speed and total confidence in self. Beyond that add opportunity and luck. Well, as a designated test pilot after Army Air Force combat fighter experience, to stay alive one concentrates on reality in the moment, knowing equipment limits and locking-out fear.

Miss Airs: General, you describe the event as simple to achieve but there must be a huge story.

CY: First, propeller-driven engines and anti-swept wing design are just unsuitable. Second, limiting air drag while maintaining flight control is critical, plus having engines with exceptionally high thrust and enough fuel to achieve the objective. Weight limits are a factor.

Miss Airs: I gather your statements posed aviation engineers a tremendous challenge and creative new designs. Aim I right that some of the new thinking came from German plans and developed planes used in WWII?

CY: Yes. No doubt what state-side companies and a few of their designers learned from those plans paved the way to making high-altitude flights possible. Our experts assessed the problem as two-fold: 1) help the space vehicle by getting it high up before launch and 2) once at targeted altitude release the vehicle and energize the new motors. The first task was relatively simple by using a Boeing B-29 that had been converted to carry a rocket ship below its wing surface. The second task necessitated both a new body design and robust engines.

Miss Airs: The next most logical questions are who made the space fuselage and who made the unique engines, right? There were numerous tests made before the history making day I presume.

CY: Our government awarded space-vehicle design to Bell Aircraft, who had made the X series. When dropped from a B-29 mother ship, several non-powered flights were made to establish vehicle stability. Some XS-1 models tested were conducted over Florida; other X-1s were tested over the Muroc Test Range, California. Note that 4-in-1 was the key to rocket engine design, or in other words, four engines in one housing. A company called Reaction Motors built the XLRII rocket engines. Fueled by a mix of ethyl alcohol, liquid oxygen and water caused the engines to yield 5,9000 pounds of thrust for four minutes.

Miss Airs: General, what is the sound barrier demon, subsonic and supersonic flight in comprehensible terms?

CY: Fancy, aerial flights poses many unknown demons such that too heavy a plane limits maneuverability versus inadequate propulsion thrust or insufficient wing surfaces to sustain pilot control. Let’s define the speed of sound as distance traveled by a sound wave over a unit of time at 32° F or more commonly 741 mph. Subsonic and supersonic are the movement of air around an object, e.g., wing, slower and faster than the speed of sound, respectively.

Miss Airs: Tell me about your X-1 and your ride when you broke the sound barrier?

CY: My test ship was a Bell X-1 # 6062, one of three, and I named her Glamorous Glennis for my wife. Luck put me in the pilot seat as another fellow test pilot became sick and unable to fly that day. The mother ship released the X-1 at 10:26 am from 20,000 feet. Once clear, I fired up all engines one by one and aimed the nose upward to 42,000 feet . Then I cut off engine fuel. At 45,000 feet with no more thrust the ship shuttered into a 1-g stall. Concluded the task with a safe landing. Official results declared the barrier was broken at 1.06 Mach at 43,000 feet or 700 mph.

Miss Airs: There must be one more thing you can say about that eventful day.

CY: You know I am sure that sonic booms occur when the barrier is broken, that is exceeding Mach 1. There were two sonic booms about 20 minutes apart heard by many in the area. A North American Aviation Super XP-86, flown by George Welch, also broke the sound barrier as well. Then he did it again in the first test flight of an YF-100A over Palmdale, CA on May 15, 1953.

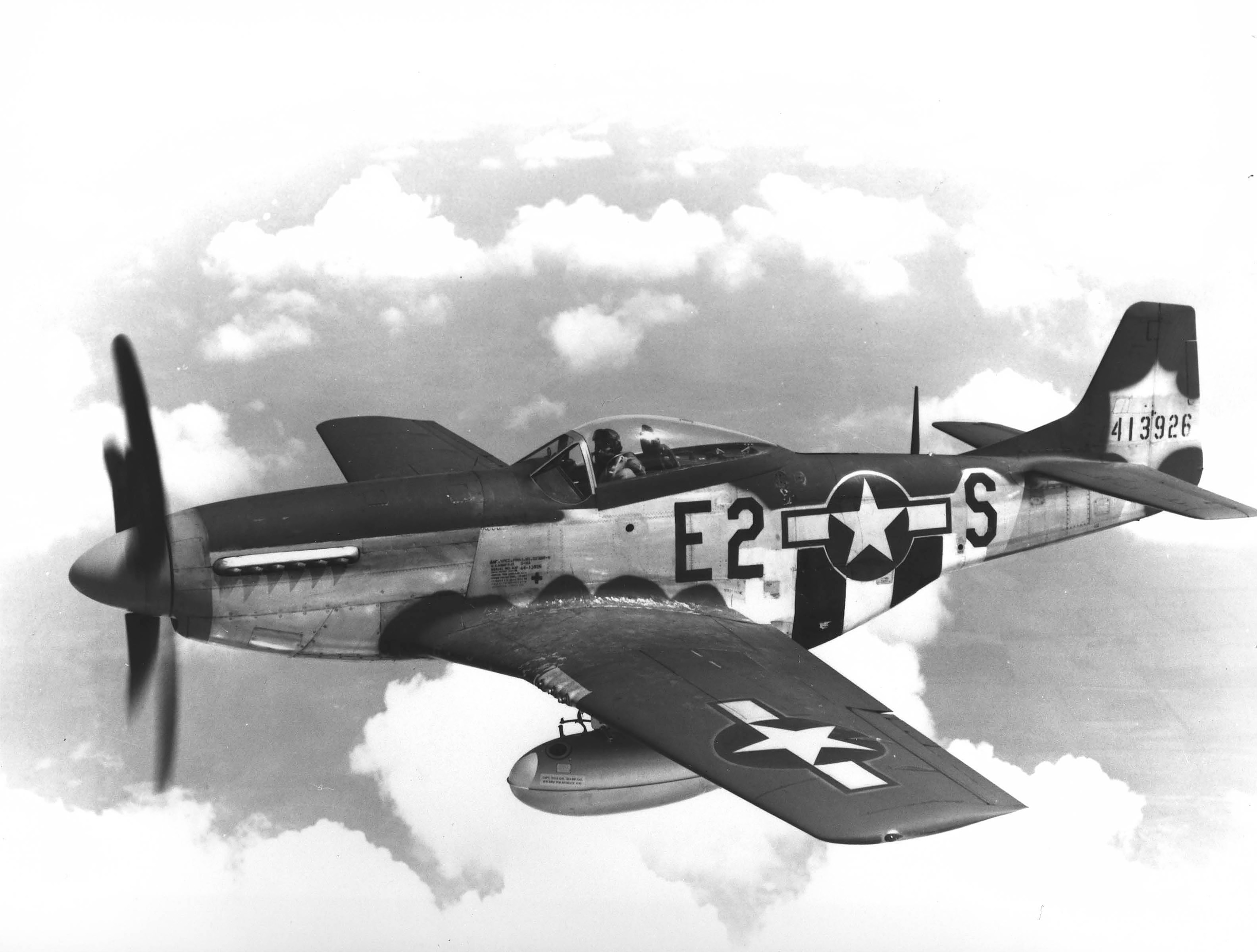

Miss Airs: General, my final question asks what was your favorite plane to pilot?

CY: Fancy that you should ask of my favorite wings in the sky. The P-51 Mustang because it acted instinctively to the pilot’s demands. That is one reason I became a combat ace.

Editor’s note: This duologue (a play or part of a play with speaking roles for only two actors) is a fictional conversation between a reporter and the man who rode the rocket ship in October 1947. This historical depiction is based on information from Dan Hampton’s book, Chasing The Demon and online research. The Bell X-1 was made in Buffalo, NY.