The Monthly Read: Bitter hearts ~ timeless relevance

by Mary Drake –

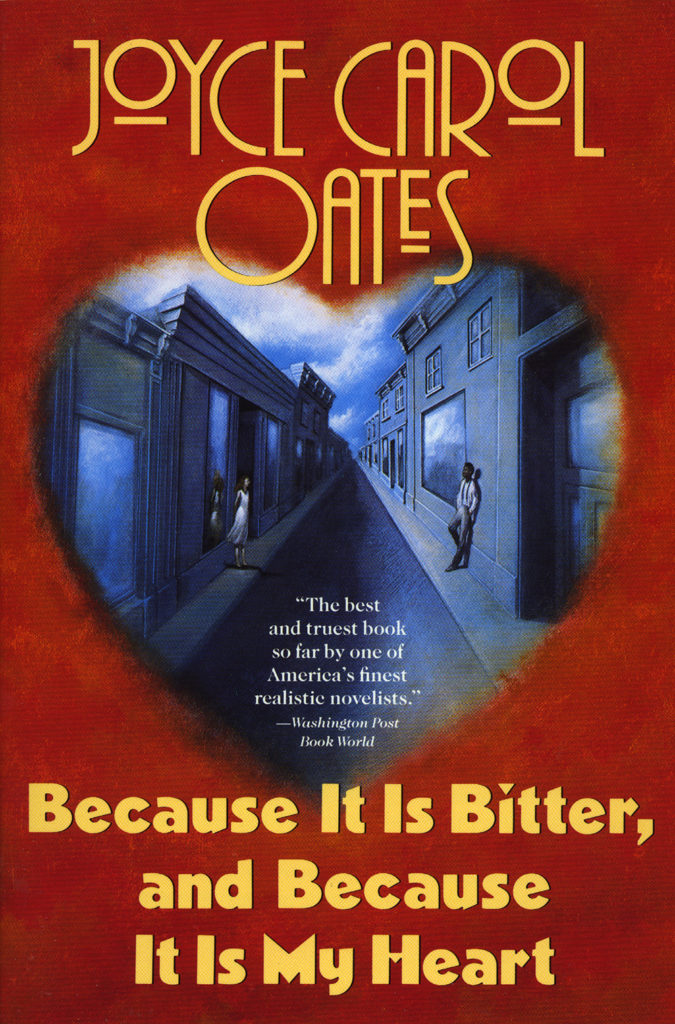

Some books age better than others. The one I recently picked off my shelf to read on vacation is one such book. Although it was published 29 years ago, it still seems relevant. The book is Because It Is Bitter, and Because It Is My Heart, written by Joyce Carol Oates. Perhaps it has aged so well because it deals with timeless subjects that are still topical today, such as race relations, social classes, coming of age, and finding one’s place in the world. Much could be written about these subjects, but a good story dramatizes how the fictional characters handle life, so that we might learn from their mistakes.

Some books age better than others. The one I recently picked off my shelf to read on vacation is one such book. Although it was published 29 years ago, it still seems relevant. The book is Because It Is Bitter, and Because It Is My Heart, written by Joyce Carol Oates. Perhaps it has aged so well because it deals with timeless subjects that are still topical today, such as race relations, social classes, coming of age, and finding one’s place in the world. Much could be written about these subjects, but a good story dramatizes how the fictional characters handle life, so that we might learn from their mistakes.

The book has also aged well because of the writing. It was nominated for a National Book Award for excellence in fiction in the year it was published, and Joyce Carol Oates herself had become well known and respected as a writer while only in her thirties.

She is a local author made good. Born in Lockport, New York, near Lake Ontario, her novels are often set in small, upstate New York towns where the weather is cold and cloudy. Because It Is Bitter, and Because It Is My Heart takes place in Hammond, New York, which could be the twin of Lockport. Like most authors, Oates uses some of her own experiences in her fiction—the main character in this novel wins a scholarship to Syracuse University, much like Oates herself. She wanted to write from an early age and was encouraged by her parents who had grown up during the Depression and been unable to attend college. Not only did Oates graduate from college, she went on to become a professor of creative writing at Princeton University, and has written 56 novels, over 30 anthologies of short stories, eight volumes of poetry, as well as young adult fiction, plays, book reviews, and essays. This prolific writer has regularly produced two novels per year throughout her long career. However, she still says that what disturbs her the most is that “I have so many ideas I consider exciting . . .that I will never live to execute because it takes me so long . . . . With all this practice, though, it’s no wonder her books are so well written.

Because It Is Bitter, and Because It Is My Heart transports readers back to the 1950s in upstate New York, and it is a far cry from Happy Days. If you thought the North had somehow escaped the racism of the South, think again. The story concerns a white girl named Iris Courtney from a poor family whose parents are alcoholics. She’s attracted to Jinx Fairchild, the star basketball player at her high school and an all-around nice guy. But there is a racial divide in their community that must not be crossed. One can look at the other, make polite conversation, perhaps even joke around and flirt, but a strong taboo exists against anything more, and crossing that line can have severe consequences. When Iris’s mother, Persia, and her “mulatto” lover, Virgil, are pulled over by the police for no apparent reason, Virgil knows that the situation is bad. The police routinely bully Negroes, and because he’s with a white woman, he’s in even more serious trouble. Persia tries to reassure him that they haven’t done anything wrong, but Virgil knows how things are: “ ‘No matter what I done or didn’t do, it’s who I am.’ He shuts off the ignition as two state troopers approach their car, pistols drawn. He says, despairing, ‘And there’s you.’ “ Using racial slurs, the troopers shove Virgil around and tear apart his nice clothes and his car looking for some phantom offense. Afterwards, Persia tearfully tells her daughter that it’s “So awful . . .seeing a man crawl.” Teaching in Detroit, Michigan, in the 1960s, Oates was in a hotbed of racial unrest, and the civil rights movement was just beginning. But a Negro character in the book mentions Martin Luther King, and she views him as more of a troublemaker than a savior.

In the society that Oates sketches, some people are more valued than others: whites more than blacks, the wealthy more than the poor, the educated more than simple folk, the talented more than the masses. Social stratification is everywhere, which is why Iris Courtney recognizes that she must keep hidden her attraction to Jinx Fairchild. But she sees him everywhere, at the local swimming hole, at school, at the corner store. When a mean white boy from a poor section of town threatens and harasses her, Iris turns to Jinx for protection. The deadly fight that ensues leaves both Iris and Jinx demoralized and guilt ridden. The rest of the book concerns how they cope with the blameworthiness of what they’ve done. Jinx keeps looking at his hands, hands that are so skilled when they encircle a basketball but that, like Lady MacBeth’s hands, have blood on them. He recognizes his guilt and would like to confess, but he’s understandably afraid what will happen to him given the racial implications. He is beloved by his teachers and classmates, but only because of his basketball talent. He comes to see himself as nothing but “a performing monkey. S’pose you decide to stop performing,” he asks himself. He knows the answer, and it’s grim.

Iris blames herself for leading Jinx Fairchild into trouble, but their secret draws them together. She tells him, “No one is so close to me as you, no one is so close to us as we are to each other.” Jinx feels that Iris Courtney is “the only white who sees him, knows him.” Because she knows who he really is, he’s attracted to her, yet her secret knowledge about him also means she could destroy him, and for a while he imagines her dead. Both wonder who they are, in relation to one another, in relation to the world. Where and how do they fit in, especially after what has happened?

Despite their guilt, the murder remains unsolved. Jinx seems destined to go to college on a basketball scholarship, but misfortune prevents that from happening. After graduation, when Iris next sees him, he’s riding in “a truck rattling by, Orleans Co. Maintenance on its side, several black men in the open rear in thick jackets, wool caps, amid shovels, sandbags, road repair equipment.” Jinx is the tallest one, and he doesn’t respond when she calls his name and waves.

Iris, being one of the smart girls, goes on to get a scholarship to Syracuse University, her ticket out of dumpy little Hammond. Her mother has died of alcoholism, her father disappeared years ago, and she has little left in the town but an eccentric uncle.

The trajectories of Iris and Jinx have gone in opposite directions. Is this because of race, or circumstances? Bad luck, or better opportunities? Whichever it is, Iris ends up engaged to an up-and-coming art student from a wealthy family who has just been offered a curatorship at the Philadelphia Museum of Art. Jinx, after a troubled marriage and several children, enlists in the army and is being sent to Vietnam. They could hardly have had more different outcomes. Yet Jinx writes Iris a parting note on the back of his picture as a proud new recruit; it says, “Honey—Think I’ll ‘pass’?” And when Iris tries on her bridal gown, she asks her future mother in law “Do you think I’ll look the part?” They’re both still playing a role in life, the ones society has assigned them, the ones their choices have led them to.