The Monthly Read: The definition of originality

by Mary Drake –

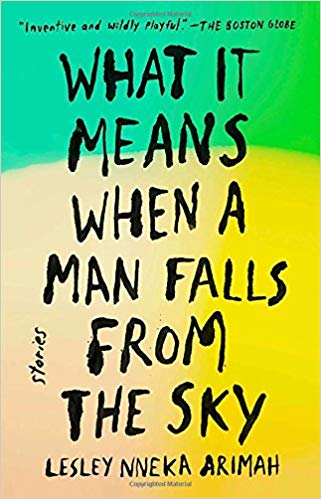

A review of What It Means When a Man Falls from the Sky by Lesley Nneka Arimah

What it Means When a Man Falls from the SKy

by Lesley Nneka Arimah

Riverhead Books (2017) 240pp

while back, my daughter gave me a reproduction of an Impressionist painting — a woman reading — and underneath the picture is the caption, “Life is short; read fast.” I feel the truth of this statement so much that I seldom re-read a book, until I find one like Lesley Nneka Arimah’s What It Means When a Man Falls from the Sky, which I read three times, and with each successive reading I noticed another perfect detail or got another new insight. This debut book is a 230-page anthology of 12 short stories by a creative writing teacher turned author whose far-reaching imagination will keep you turning the pages, not only to find out what happens, but also because you will come to care about her characters, mostly women, who are by turns humorous, difficult and compassionate, sometimes all in the same story.

Born in Britain to Nigerian parents, Arimah was subsequently raised in Nigeria and Louisiana, before ending up in Minnesota. (I’d be interested to hear her answer when people ask where she’s from.) Optimistically, you could view her travels as having given her an insider’s view of all three societies. She has the voice of a storyteller, and many of her stories have strong spiritual content that places them squarely in the category of magical realism. Arimah is very interested in the mother/daughter relationship, in the attempt of mothers to mold and control their offspring, and in the difficulties these young women often face trying to adapt to the societies where they find themselves.

I am often attracted by titles, and I found this one especially intriguing. So what does it mean when a man falls from the sky? In the dystopia of this story, it means that something has gone gravely wrong with Francisco Furcal’s mathematical Formula which, the reader is told “explained the universe,” and which “had no end and, perhaps, by extension, humanity had no end.” The Formula has become the new religion after floods have caused Europe and North America to disappear under water. The people of Britain, France and America are now “hosted” by other countries: Britain by Biafra, France by Senegal, and America by Mexico (imagine that! No wall necessary now). However, the Biafra-Britannia Alliance is tense, since the British threaten to use biological warfare if they don’t get the land they want. France gained the trust of the Senegalese before turning on their hosts and beginning ethnic cleansing in what is referred to as “The Elimination”.

In the midst of all this, The Center employs Mathematicians (with a capital M) to continually run the Formula through a computer “ticker-style across a screen” testing its infiniteness, and also, in the process, discovering equations for, among other things, human flight. “The scientific community was agog. What did it mean that the human body could now defy things humanity had never thought to question, like gravity? It had seemed like the start of a new era.” Until a camera caught the man’s fall, “the last fifty feet . . . the windmill panic of flailing arms, the spread of his body on the ground.” Now some have begun to question whether the new mathematical religion has an inherent flaw.

The protagonist Nneoma is one of the few and socially privileged Mathematicians in this new world. Her understanding of necessary equations in the Formula has enabled her to become a “grief worker.” She has the unique ability to make a living by “calculating and subtracting emotions, drawing them from living bodies like poison from a wound.” We’re told “she could see a person’s sadness as plainly as the clothes he wore.” By a simple hug she lifts the sadness from a young Senegalese refugee grieving from The Elimination. However, Neoma usually only does grief work for her “preferred clientele,” meaning those who can pay, and she is unable to relieve her father or herself of the grief they feel after her mother’s death. By contrast, her estranged partner, a woman called Kioni, volunteers to do her grief work for those who really needed it—“the displaced Senegalese and Algerians and Burkinababes and even the evacuees.”

There is probably no one who hasn’t wished to escape emotional pain at some point, but Arimah asks us to consider some interesting questions. Is it good to rid someone of emotions that differentiate us from animals? Aren’t we told that suffering can sometimes lead to wisdom? On the other hand, could internalizing too much grief have devastating consequences, as it does for Kioni? We humans can only handle so much suffering and inhumanity.

Even though Arimah deals with heavy subjects like isolation and loss in her short stories, they are easy to read, imaginative, sometimes even playful. Often they are reminiscent of folktales: the language is simple and direct, yet the subject is thought provoking; magic is an accepted part of the world; and the heroine (and by extension, the reader) is led to a new insight by the end. The author often employs repetition, as in the opening of “What It Means When a Man Falls From the Sky”:

It means twenty-four-hour new coverage. It means

politicians doing damage control, activists egging on

protests. It means Francisco Furcal’s granddaughter at

a press conference defending her family’s legacy.

This serves to overwhelm the reader slightly, piling on detail after detail. But Arimah is confident readers will figure out what’s happening in the story, even if we can’t figure out how to alleviate the suffering endured by a man falling from the sky.