Richmond History: Richmond’s remarkable recluse: Bradly Adams (February 21, 1852-February 9, 1934)

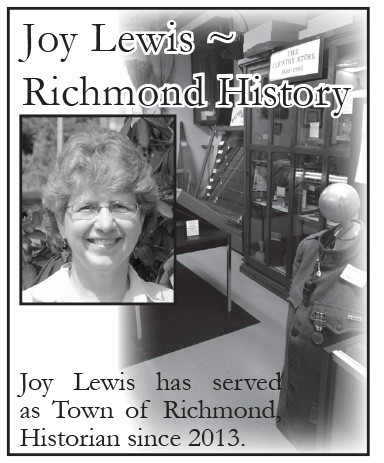

by Joy Lewis –

From the Albert R. Stone Negative Collection. Rochester Museum and Science Center.

He was a trapper, an expert marksman, a collector of Indian artifacts, an entrepreneur, a loner. From the age of sixteen, when he built a rude cabin on a back lot of his parents’ farm, Bradley Adams elected a solitary life. Those who knew him in his sunset years remembered that he was “always cheerful to meet, but he had little to say.”

Born on a winter’s day in 1852, he was the eldest child of Oscar Adams (1820-1891) and his first wife Emily Norris (1830-1864). Five more children arrived in the next decade: two boys, Henry and Ely; and three girls Emily, Bertha, and Etha. By the time Bradley’s mother passed away in 1864, two of the daughters (Emily and Etha) had also died. Oscar did not long mourn the loss of his wife, for he married within the year, taking as his second wife, Marietta, the younger sister of his first. Bradley was then a boy just entering adolescence.

The Adams farm lay on the north side of Stone Hill Road, about a mile west of Plank Road in the township of Livonia. It was a large farm, and prosperous. Oscar worked the land with the help of a couple hired men and his two eldest sons.

A childhood chum, Charles Dewey, recalled years later the escapades he and Bradley enjoyed in their early teens. They “used to go woodchuck hunting” together and experimented to learn how to burn charcoal. Charlie remembered that he and Bradley, with a group of friends, “used to have royal sport in Salsich’s old sawmill at Livonia Center, during the summer when there was no water in the flume; we used to play ‘home’ as we called it, choosing up in two groups, one going out and hiding while the others would hunt for them, and then running to a log or tree which had been chosen as ‘home.’ The old mill made many excellent hiding places and we never tired of the sport.”

During Bradley’s teen years his step-mother gave birth to four children: Moses in the first year of her marriage, followed by little Gracie, who lived but a day. Flora, the next born, also died in infancy. Addie came to them when Moses was ten and Bradley was twenty-four.

For nearly a decade Bradley had been living by himself in his one room cabin, working alongside his father on the farm from springtime to harvest, walking a trap line all winter. He found he could make a tidy profit selling his furs. For another year or two he remained at the family homestead. Then, nearing thirty, he packed up his scanty belongings and headed west.

His obituary provides a snapshot of his years in Oregon: “There [he] increased his love for the great out-of-doors, a trait with which he was born and which characterized him all of his life. It was during those years of pioneering that he gained his high regard for [Bill] Cody, [George Armstrong] Custer and others of their type, and ever since he came back to New York State…he dressed in the picturesque mode of the scout,” garbed in fringed buckskin, a broad-brimmed hat, and wearing his long dark hair in a ponytail.

In late middle age he returned to the home of his youth, where now his half-brother Moses farmed the Adams acreage. Little Addie, who’d been a charming toddler when last he’d seen her twenty years earlier, was now a woman grown. Shortly after his return from the West, in March of 1904, he gave a lecture at the Union schoolhouse in Lima on “How Oregon was Saved to the Union.”

With his customary independence, Bradley purchased two acres of woodland along the Hemlock Outlet in Richmond, only a couple miles east of his birthplace. Here he put up a sturdy cabin, collecting the foundation stones from the nearby creek. Here he was to live for the next quarter century.

Mr. H. DeLong was visiting a relative in Richmond around 1915 when he met Bradley Adams. He later wrote of this meeting and the piece was printed in a local newspaper. He gave a detailed picture of Bradley’s home:

Right across the outlet from the sugar bush [on the banks of the Hemlock outlet] dwells a hermit, a man, not old, who has…built him a little hut where he dwells in peace and contentment. [My cousin and I] crossed over on the stepping stones and ascending a little bank by means of a primitive set of steps found ourselves in sight of the castle. A cheery hail brought out this modern Robinson Crusoe, who greeted the intruder pleasantly and showed us all about his little domain. Scattered among the tree trunks were numerous bee-hives and in his little storeroom was piled up nearly five hundred pounds of honey in boxes…He had a neat little work shop ingeniously built…A mink skin was nailed on one end of the shanty, a gun leaned up in a corner, fishing poles hung on nails in the wall, and a bundle of steel traps spoke of plenty of sport during the winter. He had a little garden, where during the season he had raised tomatoes and cucumbers, but he said, “The varmints got most of them.” This man was perfectly happy and contented in his isolation. The great world hummed all about him on every side, but he cared naught. Safely ensconced in his little freehold, with enough to eat and wear, plenty of wood to burn and no petty strifes to annoy, he leads an ideal existence that many and many who would call him a crank, might envy.

Bradley enjoyed his little corner, safely tucked back from the road among the trees. Here he tended his beehives, cultivated ginseng, burned charcoal to sell, hired out during the harvest to stack straw (a job most workers found tedious), hunted in the autumn, worked a trap line all winter, and cured a variety of pelts. To sell his furs, he paid for a perennial advertisement in the Livonia Gazette, which included his photograph.

For some years Bradley operated a steam-powered sawmill which he set up near his brother’s farm. An accident with a buzz saw cost him his right hand. But as Mr. DeLong noted, “It was surprising how deftly he could work with his one hand.”

Lois Wilkins, for many years the Livonia Town Historian, wrote in 1975 of her memories of Mr. Adams as he was in the late twenties: “His yearly visit to the store was looked forward to by the grownups as well as the children…He kept his own apiary and would come into the store, a basket filled with honey hanging from the stump of his arm. He wore his long hair tied in a ponytail, and had a broad brimmed hat looking all the world like Buffalo Bill who was his idol. He was a very quiet person and always spoke in a whisper. He would sidle up to Father and put his basket on the counter, and whisper to Father about the supplies he needed in exchange for the honey. The honey would be removed, the basket filled, and he would depart as quickly as he came.”

Gertrude Reed, who recalled, “Bradley once planned a trip to visit his sister in Washington, D.C. and asked our family to take him to the train,” supplies another memory of that time. “On the day he was to leave, Bradley arrived at our house, prepared, so he thought, for his journey. Mother Reed, however, had other ideas on his readiness for departure.” ‘Bradley Adams,’ she scolded, ‘you are not going to Bertha’s until you have a bath!’ Hauling the old washtub into the middle of the kitchen floor, she filled it with warm water and left the room. Bathe he did, and it was probably his first bath in anything but the waters of Hemlock Outlet in many, many years.”

It was about 1920 when his cabin caught fire and burned to the ground. The Livonia Boy Scout troop came to his rescue. Some years earlier, on a small patch of land owned by George Reed, the boys had built themselves a meetinghouse. This was a snug, well-built structure eight feet by sixteen, made from lumber they rescued from the building of the library. When they learned that Mr. Adams was sleeping outdoors, they offered him their little clubhouse. He moved with the few belongings he’d been able to salvage to the new cabin. Being unwilling to be a charge on anyone’s good will, he agreed with Mr. Reed to pay a monthly rent of twenty-five cents.

On January 17, 1933, in the dead of winter, this cabin also succumbed to fire, destroying Bradley’s collections of guns and Indian artifacts and all his furs. A piece in the Livonia Gazette tells the story: “For the second time within a few years Bradley Adams has been driven out of his home by fire. Tuesday morning about 7 o’clock flames took the building where he lived on the George P. Reed farm in Richmond. He lost everything he had except the clothes in which he was dressed. His feeble condition prevented his saving his guns, tools and other belongings. He had on only one shoe; the other was burned. He himself was considerably burned about the head, shoulder, and hand, but these wounds while painful are not considered serious. He was taken to the Ontario County Home at Hopewell Tuesday.

“[The] fire was caused by the pouring of kerosene on the fire [in the stove]. George Reed had been down to help Mr. Adams with the fire and other details for the last two weeks, and it is not known just why Mr. Adams started the fire himself Tuesday. He did, however, and when it failed to respond to suit him he applied the kerosene with disastrous results.”

A month short of eighty-one at the time of the fire, Bradley remained at the county home for nearly a year. In December he was taken to a residence in Ovid, where he died two months later.

Let his obituary have the final word: “Bradley Adams’ peculiarities were accentuated by his unusual dress and appearance, but those who knew him best speak not only of his kindly nature but of his extensive knowledge along lines in which he was particularly interested. He was notably a student of the Civil War and extremely well read in history. How he was able to live as he did for so many years is a source of wonder even to those in the vicinity who befriended him so constantly.”