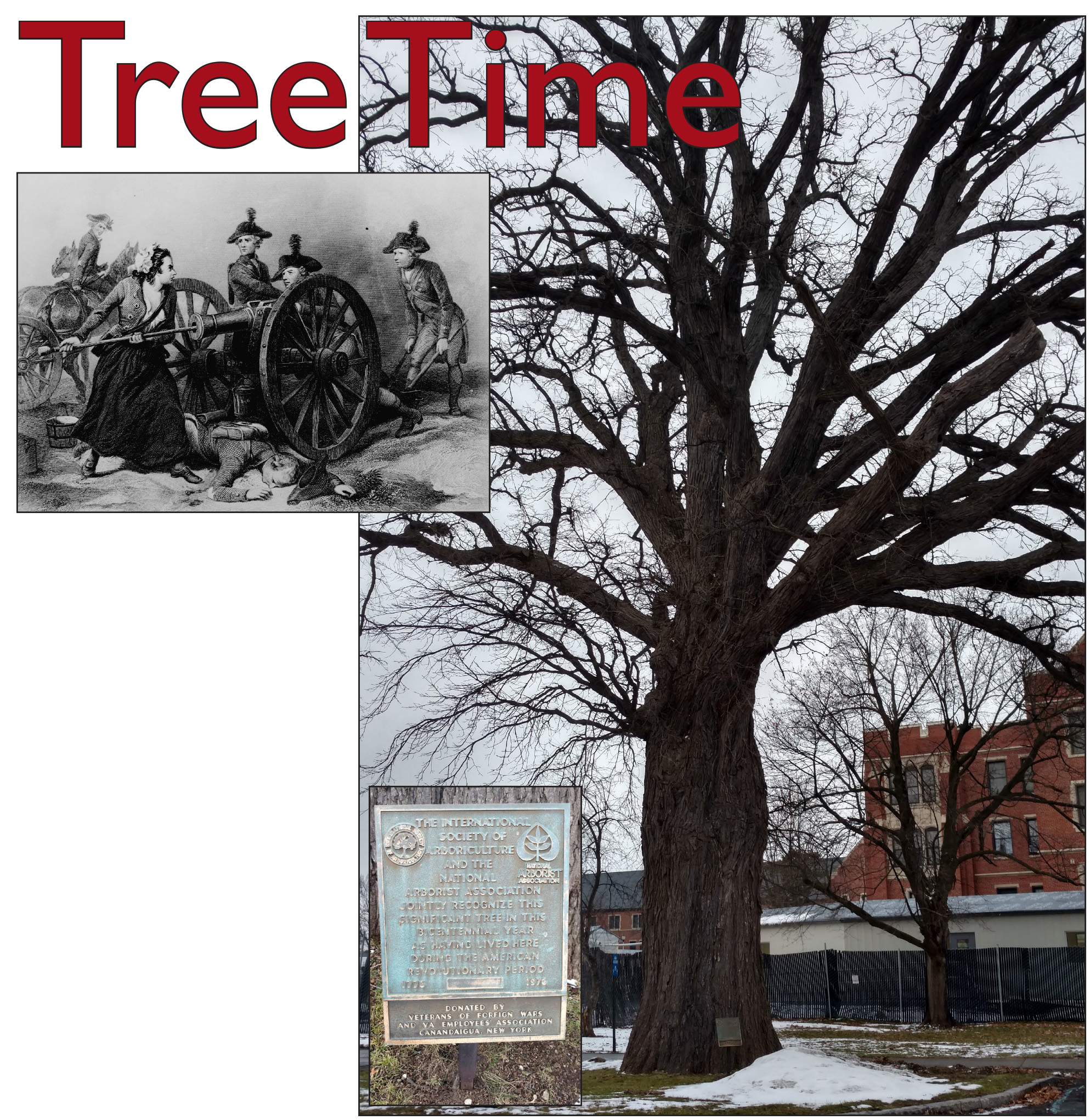

Tree Time

by D.E. Bentley –

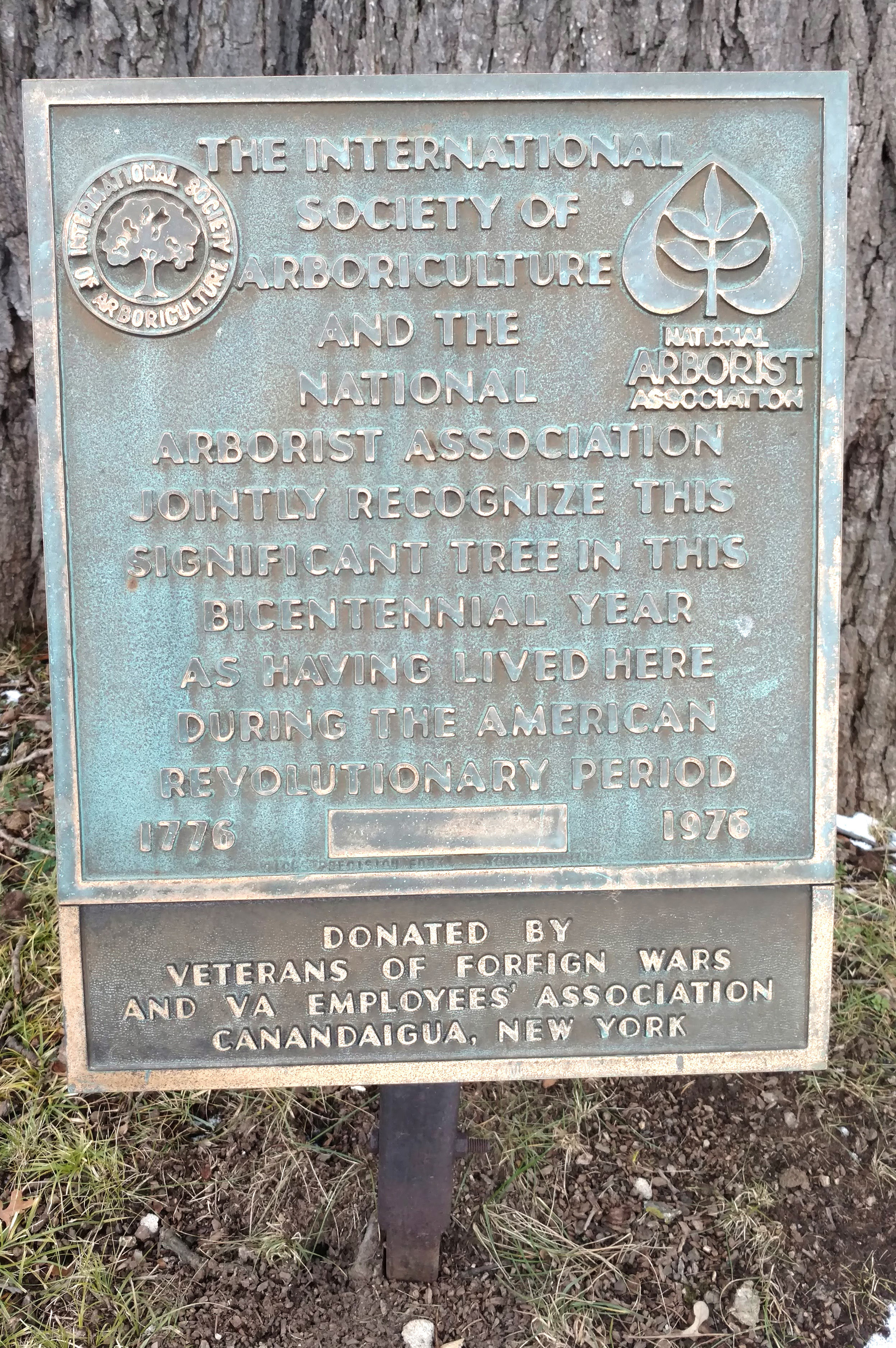

I had previously noticed the tree, a Bur Oak, casting its great shadow across the walkway in front of the Veterans’ Hospital in Canandaigua, New York. I had also noticed the plaque at the foot of the tree, but had never taken the time to read the words embossed into the metal. On December 12, 2018, a veteran leaving the facility at the same time as me walked toward the base of the tree, greeting some friends as he passed them by. I was parked in the closest space, and he asked if it was my vehicle since we walked in the same general direction. He explained that he was going to read the plaque, and then stood quietly reading the words – inspiring me to do the same.

I looked up at the tree, its branches bare, and noticed a few clinging oak leaves. The Bur oak (Quercus macrocarpa) is in the family Fagaceae, along with other oaks, beeches and chestnuts. Quercus is the Latin name for oak. Macrocarpa comes from the Greek Makros meaning “large” and karpos meaning “seed” in reference to the large acorns. Other common names for bur oak are mossycup oak and scrub oak. The tree is known by the Lakota as u’tahu can, meaning “acorn stem tree.” Other Native American names for the bur oak are tashka (Omaha), chashke (Winnebago), and patki natawawi (Pawnee). The Bur Oak is a widely distributed oak in Eastern North America, native to North America (from Nova Scotia to Manitoba, south to Texas). They are very resistant to fire injury and develop a deep root system early on, increasing their resistance to drought and offering them longevity.

Its leaves are deciduous, alternate, simple, 6 to 12 inches (15 to 30 cm) long, with 5 to 9-rounded lobes. Bur oak flowers appear on old or new wood, often as the leaves unfold. The flowers occur on several to many flowered spikes. The fruit is a nut (acorn) about 1 inch (2.54 cm) or less in length with one-half or more of the nut enclosed in a fringed cup. Twigs are stout, usually covered with corky ridges after a year or two. The bark is dark gray with deep vertically aligned ridges.

There are some of these individuals living quite near to where I live; I have found their distinctive acorns – a squirrel delicacy – scattered trailside. Few ever reach the size of the tree at the Canandaigua VA. At the time of the tree’s commemoration, measurements taken by the New York State Forestry Service put the tree at 90 feet high with a circumference of 18 feet 5 ½ inches (measured 4 ½ feet from the ground) and a crown diameter of 100 feet. At that time, the tree was estimated to be 265 years old. The bur oak’s average lifespan is between 200-400 years.

In 1976, when the Tree was dedicated, the Veterans’ Hospital was in its forty-third year of service to America’s Veterans. The lands on which the Canandaigua Veteran’s Administration Medical Center – as it is now known – and the tree, are firmly rooted was purchased by the United States Government in 1931 from the Sonnenberg Estate. An additional 362 acres – most from the Bacon Farm – were subsequently purchased and added to the original 118 acres. The earliest patients, who arrived by train in 1933 after the completion of the first buildings on the expansive grounds, farmed much of the acreage. The tree – if it was in its infancy in the mid-1700s, as its estimated age would indicate – already stood tall in front of Building 1.

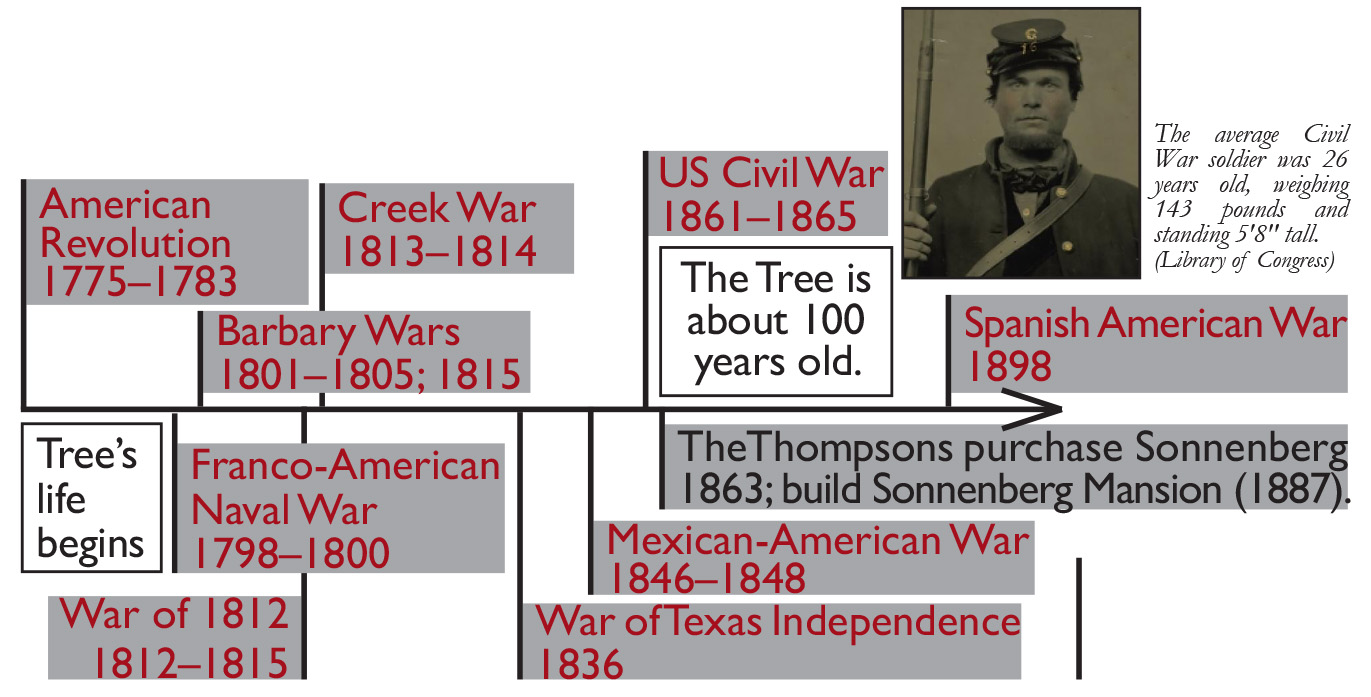

She had been there already when the Revolutionary War began in 1775; it lasted for 8 years. The majority of the war was fought in New York, New Jersey and South Carolina. There were six New York State Regiments and an artillery company. It was a time of hope – and death – that must have seemed endless. Women joined the fight – in some cases following their husbands and sons onto the battlefields where they assumed domestic roles and cared for the wounded. Some fought on the front lines, as was the case with Mary Ludwig Hays (Molly Pitcher) who took over in artillery after her husband was wounded at the Battle of Monmouth in 1778. Margaret Corbin, severely wounded at Fort Washington in 1776, was left for dead alongside her husband (also an artilleryman). She survived but was left permanently disabled, and subsequently became the first American female to receive a soldier’s lifetime pension. Both free and enslaved African Americans fought; many of the estimated 9000 Black Patriots believed in the Patriot cause – some were promised freedom for helping to fill the regiment ranks. Smaller numbers joined the Loyalists. The War became a civil war for the Haudenosaunee – with tribes divided between the British (in the hopes of protecting their homelands from colonial encroachment) and the American Patriots. Many tried for neutrality, but their remaining lands had become a battlefield for American independence. During the infancy of the tree, the Haudenosaunee (Iroquois) had still occupied portions of their homelands in Canandaigua – “The Chosen Spot.” During the Revolutionary Period thousands more perished, and their lives and lands would never be the same. A decade after American Independence, most of those that remained had been forced onto reservations; although the Canandaigua Treaty of 1794, also known as the Pickering Treaty (one of the earliest) was signed between the Haudenosaunee (Six Nations Iroquois Confederacy) and the United States of America (ratified January 21, 1795), offering the potential for peace between these two sovereign nations.

It is impossible to determine the exact cost of human life during the Revolutionary Period. According to Battlefields.org, the British lost approximately 24,000 men and an additional 1,200 Hessian (German soldiers conscripted by the British). Estimates are that 6,800 Americans were killed in action and almost as many were wounded (at a time when hospitals were housed in homes, churches and barns, anesthesia was not in use and amputation was a common outcome – for those who survived). Many others died in unsanitary conditions and as prisoners of war. According to Militaryhistorynow.com, John Gray of Virginia was the last verified surviving American Veteran of the Revolutionary War. Gray joined the Continental Army at 16 (soldiers as young as 15 could fight – with parental consent) in 1780. He died in 1868 in Ohio, at the age of 104, having witnessed the triumph and devastation of the Civil War.

The Tree was there as well during the U.S. Civil War (Apr 12, 1861 – Apr 9, 1865), when 2,128,948 men enlisted in the Union Army, including 178,895 black troops; 25% of the white men who served were foreign-born. Information about some of the Union (and Confederate) soldiers and sailors can be found in a searchable database at: www.nps.gov/civilwar/soldiers-and-sailors-database.htm. The war took more lives than any other American-involved conflict to date. Roughly 2% of the population – an estimated 620,000 – lost their lives in the line of duty. New York lost more than any other state, with more than 35,000 deaths – as many from disease as from combat. As a nation we were ill prepared for the largest human catastrophe in American history, with, as noted on Battlefields.org, “no national cemeteries, no burial details, and no messengers of death.” Approximately one in four men never returned home, although inaccuracy and loss of muster rolls and casualty lists make it impossible to fully comprehend the loss that resulted from this fight for freedom. It was during this time – in 1863 – that Frederick Ferris and Mary Clark Thompson (newly weds at the time) purchased Sonnenberg (“Sunny Hill”) in Cananadaigua for their summer estate. Twenty-two years after the Civil War, they had completed the mansion that remains on the hill at Sonnenberg. It was after her husband’s death that Mary Clark Thompson began to dedicate her life to the gardens that are today gradually being restored to their early grandeur. *

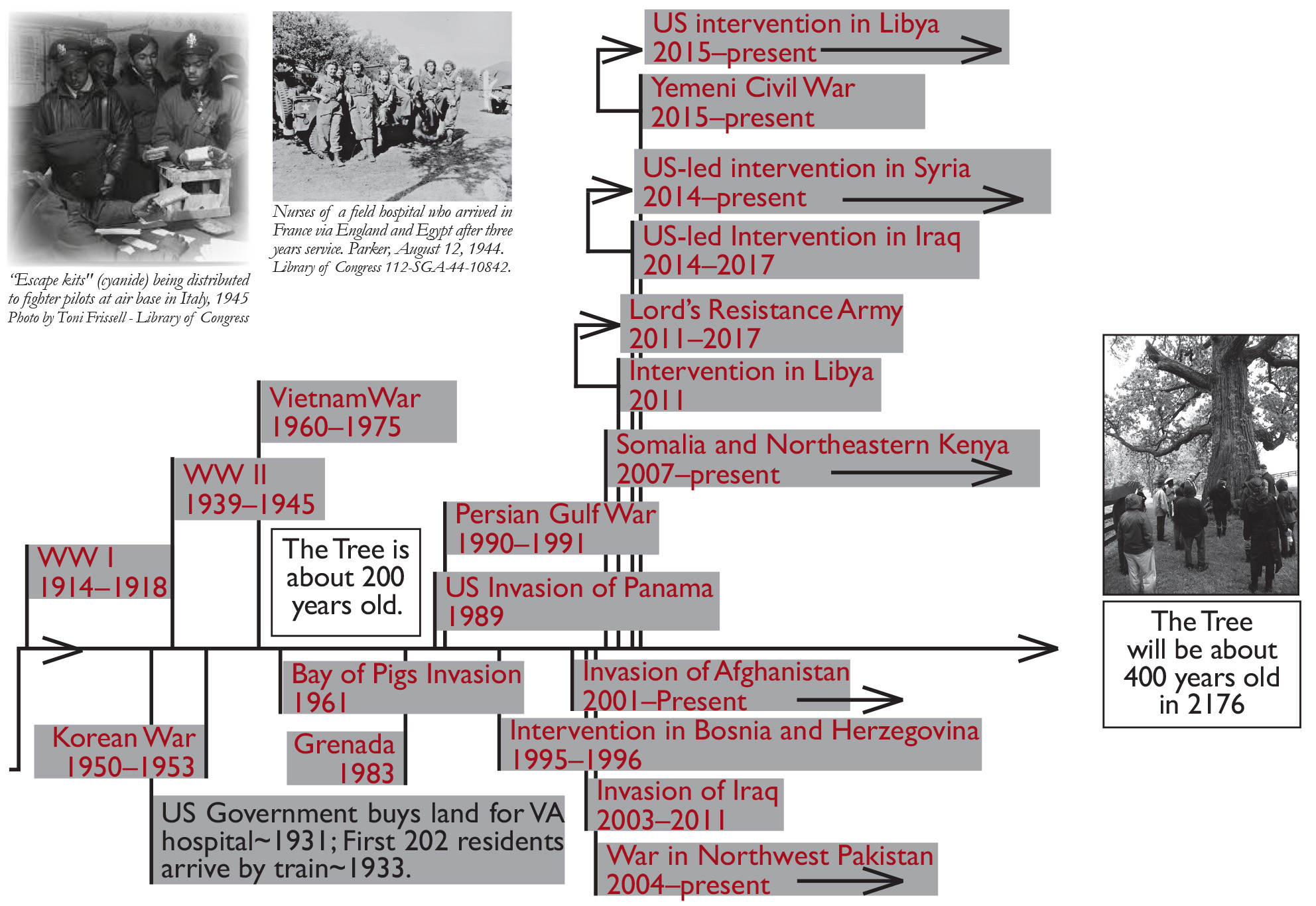

By 1931, when the US broke ground for the Veteran’s Hospital, most of those that fought for freedom in the Revolutionary War had faded from memories – the gravestones that remained slowly sinking into the earth – and one hundred more years of war had passed. It was the Veterans of World War I – the “war to end all wars” who arrived by train in 1933. More than a decade after the War’s end, deep scars remained. They came to farm the land around the tree and rest in the shadow of her grand canopy, trying to replace nightmares with moments of quiet reprieve. It was a short time of peace. A decade later war again loomed on the horizon and young men – and women – were again called forth to fight in WWII; and after that in the Korean War; and then in the Vietnam War.

For many of The Canandaigua VA’s earliest arrivals, their call to serve came as a result of the Selective Service Act of 1917 – which created the Selective Service system that remains in place today. 2,810,296 young men (21-30 years old) were drafted during WWI; 10,110,104 (18-37 years old) during WW II; 1,529,539 (19-26 years old) for the Korean War; and 1,857,304 (18-35 years old) for the Vietnam War. Initial draftees were prioritized based on familial responsibilities and, later, enrollment in college, although during various periods of conflict these guidelines were suspended. Periods of conscription were twelve months during WWI and at the start of WWII. It was extended to the duration of the war in 1942, after the US declared war on the Empire of Japan and Nazi Germany. There was opposition – particularly during the Vietnam War, which many saw as an unnecessary and unjust conflict – resulting in deadly riots in New York and draft dodgers – men who crossed into neighboring countries to avoid conscription – and prison. Despite many wanting to fight for freedom at home and around the globe, there was no way to avoid the realities of war and the impact on those that served and on their families back home.

**Standing its ground in front of Building 1 at the Canandaigua VA, the Tree remains, a silent witness to the horrors of the wars that first prompted the draft and the wars that have followed. Below they come and go, nursing the pain of the past. The VA health care system serves about 200,000 patients a day – the largest of its kind in the United States – a dire and trying task. Recognizing this challenge and those who have served, President Obama in 2014 took action for change by signing into law a $16.3 billion plan to overhaul the nationwide health care system run by the Department of Veterans Affairs. “This will not and cannot be the end of our effort,” Obama said. “Implementing this bill will take time. It will take focus from all of us.” The bill included provisions for hiring additional VA doctors – including specialty care physicians — nurses, mental health professionals and other medical staff. To address shortages in care, it also allocated $1.27 billion to pay for 27 new medical centers in 18 states and Puerto Rico. In Canandaigua, the Canandaigua VA Medical Center Mega Project (a 5 year project facilitated jointly by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers and the Department of Veterans Affairs) will provide a state-of-the-art medical facility and health care service infrastructure to approximately 65,000 veterans living in and around the greater Canandaigua, NY area.

Based on our November 2018 mid-term elections, war and the cost of war continue to influence Americans. Over 200 veterans ran for office, with 18 veterans winning their first term in the House of Representatives and one in the Senate. Even with these recent additions of veterans, the number of members in Congress with previous military experience is still 40-60% below what it was in the 1950s-60s. Many American’s have forgotten that we are at war and have been at war continuously for the past seventeen years. In contrast to earlier wars, the impact of more recent conflicts are not felt as directly at home. There are no battles being waged on our soil and no conscription of our young. Our homes and places of worship are not makeshift hospitals. They are felt in the places where those wars are being waged and in the military family – both those deployed and those left behind.

These losses are often felt more devastatingly when they are our neighbors, our loved ones. As with the deaths on January 16, 2019 of Shannon M. Kent, 35, of NY (Navy Chief Cryptologic Technician); Army Chief Warrant Officer 2 Jonathan R. Farmer, 37, of Fla.; Former Navy SEAL Scott A. Wirtz, of Mo., a US defence contractor – and (10) other people in an ISIS-claimed bombing of a restaurant in Syria. The wars we now face leave enduring wounds, with devastating consequences beyond the battlefields. War and military build up has become a “normal” and almost accepted part of our lives – as battles rage around the world and soldiers return to piece together home lives they left behind.

On January 17, 1961, President Dwight Eisenhower in his farewell speech from the White House warned of what he called the military industrial complex. He was concerned about the potential for fears and an increased emphasis on the building of weapons of war to result in a misbalance of power. He cautioned his fellow Americans:

“In the councils of government, we must guard against the acquisition of unwarranted influence, whether sought or unsought, by the military-industrial complex. The potential for the disastrous rise of misplaced power exists, and will persist.”

He also recognized the cost of an arms race and the potential for funds allocated to weaponry would be taken from schools and hospitals – including hospitals established to care for those who have already served. He believed that “we must learn how to compose differences not with arms, but with intellect and decent purpose.”

Moving forward, the United States and her egalitarian-minded allies must find ways of resolving domestic and international conflicts without sacrificing our loved ones or the loved ones of people around the world – most of whom are everyday citizens caught up in conflicts beyond their control. Looking at the wars that have transpired since the life of the Tree began leaves me wondering what the future holds for the next one hundred years. In this tree’s time, we have gone from fighting wars with muskets, bayonets and tomahawks to wars waged with robotics, unmanned systems and biological weaponry. She stands rooted, unable to act, as below her canopy the cost of wars past roll by. Like the tree, we all wait for the new day – wondering what future will emerge by the dawn’s early light.

* Our ability to enjoy the Sonnenberg legacy is due to dedicated citizens who, beginning in 1966 begun to purchase a 50-acre portion of the original estate and gardens back from the Veterans Administration. They set about to preserve and restore the Mansion, gardens and greenhouse complex. A legal transfer of the estate from the VA to Sonnenberg Gardens, a not-for-profit organization, was passed and signed into law in 1972. Formal restoration began in 1973, with plans drawn up from original blueprints and photographs (including garden details) and Sonnenberg Gardens opened its gates to the public in May of that year. In March of 2006, the property was “purchased” by New York State and is now operated by the non-profit in a cooperative (5) year renewable agreement with NYS Office of Parks and Recreation but receives no tax monies or state funding for daily operations. Restorations continue with a small year-round staff, a growing base of hundreds of seasonal volunteers and revenues from seasonal visitor admissions, annual memberships and donations, public or private special events and a seasonal retail gift and wine center.

** In 1969, selective service became a lottery system and in 1971 another amendment made Military Selective Service compulsory. Compulsory registration was eliminated in 1975. Five years later – in response to the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan – Selective Service was re-established – requiring all 18-26 year old male citizens born on or after January 1, 1960 to register. Beginning in 2014, bills to abolish and change Selective Service System (including a bill to order young women as well as young men to register) have been introduced, but no change has taken place. (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Selective_Service_System).

Selective Service System registration forms with “Men you can handle this” printed at the top can be found in most US post offices. Currently, “All male US citizens between 18–25 (inclusive) years of age are required to register within 30 days of their 18th birthday.” Certain categories of non-US citizen men between 18–25 years of age must also register. There has not been a draft since Jan. 27, 1973, as the end of the Vietnam War came into sight. Today’s United State’s armed forces are voluntary, offering for many a career path, opportunities for affordable education after high school and a chance to make a difference. According to Defense Department personnel data, there were a total of 1.3 million active duty military and more than 800,000 reserve forces as of September 2017. As of 2016, there were 6.8 million Vietnam veterans and 7.1 million Gulf War veterans (classified as those who have served from 1990 to present times, although there is some overlap between the two).