Dragonfly Tales: Liberty Hyde Bailey

by Steve Melcher –

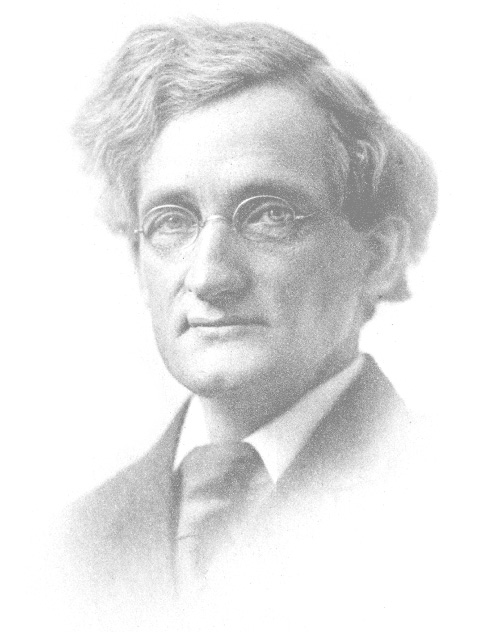

The Father of Modern Horticulture –

Liberty Hyde Bailey is one of my greatest influences and someone who I believe to be an unsung hero of today’s Nature Movement. Odonata Sanctuary, where Ilive, is home to the Center for Sustainable Living as well as the American Nature Study Society. The American Nature Study Society (ANSS), an affiliate of the American Association for the Advancement of Science, is America’s oldest environmental education organization. Liberty Hyde Bailey, of Cornell University’s Bailey Hall fame, became the society’s first president in 1908. This scrappy botanist, now known as the Father of Modern Horticulture, became an expert in palms and travelled the world searching for different horticultural varieties. Dr. Bailey was born in the rough frontier land of Michigan in 1858. His father, of the same name, “tramped all the way from Vermont, carrying fruit trees for the West,” a veritable Johnny Appleseed. In fact, his son, our very own Liberty Hyde Bailey, was awarded the Johnny Appleseed Bronze Medal in 1947 for his work in fruit horticulture. Dr. Bailey was raised on a farm in Michigan on land cleared of forests by his father. The family farmed the tract, made its own soap and candles, tanned its leather for shoes and horse bridles, wove its cloth, fought off bears and made friends with the ‘indigenous folk’. After graduating from Michigan Agricultural School, Bailey attended Harvard University to work with the world-renowned botanist, Asa Gray. He moved to Cornell in 1888 to take a position as Chair of the College of Practical and Experimental Horticulture. He continued his work at Cornell, where he was influential in the organization of extension programs still popular today, designed to teach natural studies and farming practices to people in rural areas. Due to Bailey’s influence and the program’s astounding success, the Legislature passed a bill in 1904 establishing the New York State College of Agriculture at Cornell and Bailey became the college’s first dean. While Dean of the College of Agriculture, Bailey appointed the first female professors and created the Bailey Hortorium, one of the largest collections of preserved plant material in the nation. One female professor appointed by Bailey, Anna Comstock, went on to publish ‘The Handbook of Nature Study’. Originally written in 1911 for elementary school teachers, this book is still used today by homeschoolers and nature oriented public and private schools. The ANSS, under Comstock’s direction, published a monthly “Nature Review” as well as the journal “Nature Study” (later edited by yours truly.). Dr. Bailey worked diligently to keep folks on the family farm and to show the “holiness” of rural living. In 1908, President Teddy Roosevelt appointed a Commission on Country Life, with Bailey as chair. Bailey described the country life movement of that time as “the working out of the desire to make rural civilization as effective and satisfying as other civilization.”

Dr. Bailey was the “Indiana Jones’”of the plant world. Before taking his position at Cornell he had traveled abroad to study herbaria in Europe. Keep in mind this was all by steam and sail. Bailey brought back samples from China in 1917; Trinidad, Venezuela, and Cuba in 1929; Hispaniola, Guadeloupe, and Martinique, Mexico in 1940; and in 1947, at age 89, samples were smuggled in from Brazil. The renowned botanist travelled over 250,000 miles to collect more than 275,000 plants. Curious, but perhaps absent minded, Dr. Bailey thought nothing of making a trip to the West Indies to search for palms at age 91; after obtaining permission from the airline to fly as a “senior citizen”. The surprise birthday party planned for him at Cornell over Christmas break that year had to be postponed because he was late for his return to campus and was wandering through the jungles of the Lucayan Archipelago in the West Indies. Bailey published over 1300 articles, 65 books, a collection of poetry, and 24 albums of plant photography. One of the largest collections of his works in New York is housed here at Odonata Sanctuary.

The stories of Professor Bailey are still told in the halls of Cornell. He lived a long, active life with a flair for the spotlight and a discipline for science exploration. As a professor, he would sometimes enter the classroom lecturing and finish while walking out the door. He was known for giving his talks while standing sideways looking out a window, one hand writing on the chalkboard and then startle a student by calling him by name to answer a question. He would pepper his lectures on growing potatoes and the taxonomy of tomatoes with tales of being mugged in Korea or the time he was washed off his boat by a tsunami while in Trinidad. The drama extended to the end of his life, where at age 90, while attending a conference in Chicago, he was befuddled by a newly installed ‘revolving door’. Although he had travelled to China by Clipper and Brazil by propeller plane, he had never gone through a revolving door before. On his second or third trip around the revolving rascal he fell out onto the pavement and broke his hip. He never quite recovered from the incident and sadly died on Christmas Day in 1954, after having taken a spin and a spill in that revolving door.

Bailey’s stone cottage, Bailiwick, still stands on the western shore of Cayuga Lake. His “Nature Study” ideas are experiencing a renaissance today with efforts such as the “No Child Left Inside” movement, works of the Children & Nature Network, and locally at Cummings Nature Center, Burroughs Audubon Society and Odonata Sanctuary.

“To farm well; to provide well; to produce it oneself; to be independent of trade, so far as this is possible in the furnishing of the table, – These are good elements in living.”

“Every man in his heart knows that there is goodness and wholeness in the rain, in the wind, the soil, the sea, the glory of sunrise, in the trees, and in the sustenance that we derive from the planet.”

From The Holy Earth by Liberty Hyde Bailey

Further reading:

•The Holy Earth, L.H. Bailey 1915.

•Handbook of Nature-study, Anna Botsford Comstock 1911

A note of thanks from the author:

The land that Odonata Sanctuary is on is divided into three intersecting purposes: organic farming, habitat management and farm animal hospice.

I’ll relay the story of finding and purchasing the land that eventually became a sanctuary in another article, but needless to say, I am grateful to the Taylor family for making the property available to us. Joe, Mary and Betsy Taylor had promised their parents, Joseph W. and Helen, that they would only sell the land to someone who would not grow houses but rather conserve the land for future generations to enjoy nature.