Homestead Gardener: Making Biochar

by Derrick Gentry –

Making Biochar – Earth Rise – One Wild and Precious Life –

Making Biochar at Home

Charcoal — the ghostly cipher-like fossils of what was once organic matter — is among nature’s more fascinating elemental substances. Carbon in the form of charcoal does not break down when it is put in the soil. And while charcoal has no nutrient value and is not an amendment in that sense, there are many reasons why one should put as much of it as possible in one’s garden.

What is the big deal with so-called “biochar,” another name for charcoal when it is added to the soil? Charcoal, as we all know, is highly porous and absorbent. That’s why it works so well in filtration systems and for treating ingested poison. In the soil, though, biochar offers an excellent medium for retaining nutrients as well as a porous habitat for a whole range microbial life (fungi, bacteria, nematodes, protozoa, and the rest of the gang). Biochar helps keep nutrients in place in the soil, in stable and plant available forms, which is just as much of a concern for the gardener as getting nutrients there in the first place. To some degree, biochar also helps with water retention in the soil. I will have more to say on all of this in a later column.

Winter is a great time for making biochar and getting it ready to put in the soil. Last year, I bartered with a friend for some biochar that he had made. This year, I have begun making it at home in my wood stove with its modest-sized firebox. Biochar, like all charcoal, is the end product of pyrolysis — which simply means “thermal decomposition without combustion.” The trick is to heat the organic material you want to convert to at least 300 degrees F within a kiln-like container that keeps most of the oxygen out (thereby preventing combustion) but allows the organic compounds in the material to gasify and burn off.

The method I use involves a stainless steel steam pan, like those used at hotels and restaurants, with a snugly fitting lid that seals the interior from oxygen but allows just enough space for gases to escape and burn off in the hot wood stove. I fasten the lid a little more tightly – but not too tightly – with small C clamps at the four corners. Simply fill the steam pan with the material you want to convert, tighten the lid, and set the pan on top of your burning fuel in the fire box of your stove where it should remain for a few hours at a sustained temperature of above 300 degrees.

What material can you convert into biochar? Any organic matter, really. I like to pull out branches from our brush pile that are bigger in diameter than kindling but small enough to cut to length with a pair of standard loppers. I choose wood that is still green, slightly rotted and “punky,” or otherwise not optimal even as kindling. I also break up pieces of the thicker bark that falls from split wood. You can even use cedar and spruce branches that should never be burnt in the stove. It does not matter what “bio” matter gets used when making biochar, because all of the volatile compounds (the formaldehyde and the creosote, etc.) are burned off during pyrolysis.

The process is not quite over once you pull it out of the oven. The char produced must be ground up into coarse bits. I do it by hand with a large metal tray and a simple mortar and pestle set up. And before it is added to the soil, the char must be “inoculated” with nitrogen and other nutrients so that it does not soak up (and tie up) what is already there in the soil. At the rate we are going, we should produce a total of about 50 five-gallon buckets of ground up char, which will easily cover a garden bed of about 600 square feet. I will have more to say about this part of the process come Spring.

***

There are dangers to reductive thinking, so let’s not get carried away with our minds of winter. In the 19th century, the chemist Justus von Liebig attempted to unlock the mysteries of soil fertility from a newly modern scientific point of view. Instead, he focused an inordinate amount of attention on only three macronutrients – the now iconic NPK – and inspired what another gardener I know of calls the “cake mix” approach to building soil. The discovery of this simple explanation also inaugurated the era of chemical dependency that still defines our industrial agriculture system. Von Liebig must be given credit, though, for unwittingly inspiring what became the organic and homesteading movements of the 20th century.

In the middle of the blooming and buzzing of the growing season, it is easy to take the ecological high ground and reject the reductive NPK mindset and give credit where credit is mostly due – to process and complexity and the symbiotic life of the soil. But the reductive chemist’s elemental point of view is nevertheless one that is worth adopting from time to time. We need occasional reminders of the sometimes sharp line between the living and the dead, between the complexity of the life process and the relative simplicity of the essential but lifeless components. In this dead of winter, with its dormancy passing for deadness, it is the perfect time for contemplating this interface.

It is not the only opportunity. Another little epiphany comes when the ground is not frozen and I am able to dig post holes, sinking them the required two feet below the frost line (I think of Frost’s “Mending Wall,” probably the finest poem in English on the subject of frost heave…). Dig down a foot or so below the cushion of sod, a little less in other places and a little more in others, and we pass a liminal zone between the hard and lifeless inorganic subsoil below and the thin layer on the surface where a teaspoon of soil contains billions of microbes, the place where things literally come to life.

Last Christmas marked the 50th anniversary of one of the most striking images of this sharp boundary between life and non-life. On December 24th 1968, astronaut William Anders looked out the window of the Apollo 8 spacecraft, retrieved his camera with color film, and took what is now known as the iconic “earth rise” photo. It is an image of a fragile and bright blue Earth, set in sharp relief against the lifeless nothing that is most definitely there as well, cold and empty and black as charcoal. It has been called “the most environmental photograph ever taken.” Yes, but for me it is also a great image to contemplate during winter, and it signifies not a memento mori, but rather a stunning memento viveri.

***

One Wild and Precious life

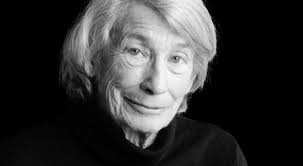

So it is over: We have survived the big snowstorm and the big chill of January. Lyle is doing a little better this morning; he weathered the stretch of single-digit nights we’ve been having. Sitting by the wood stove, I go online for no particular reason and check the official snowfall amounts, where I see news that the poet Mary Oliver has died.

So it is over: We have survived the big snowstorm and the big chill of January. Lyle is doing a little better this morning; he weathered the stretch of single-digit nights we’ve been having. Sitting by the wood stove, I go online for no particular reason and check the official snowfall amounts, where I see news that the poet Mary Oliver has died.

Oliver was a best-selling poet. One doesn’t get to write those words very often. She also wrote what is surely the finest poem on skunk cabbage in the English language. Oliver was a poet of natural piety, a so-called “nature poet,” whose voice had an honesty and a directness that resonated with a remarkably large audience of readers but inspired in others a strange sense of discomfort.

I wonder why that is. Like Robert Frost, Oliver is both widely read and at the same time in danger of being under-appreciated. Oliver stated that “poetry, to be understood, must be clear … It mustn’t be fancy.” This sounds quite different from the assumption that “poets in our civilization, as it exists at present, must be difficult.” This is what T.S. Eliot — the one who wrote the poem from a tuber’s point of view — famously suggested that poetry needed to be if it wanted to be taken seriously and counted among the fine stuff.

I was schooled in the Eliot view and taught to regard with suspicion any poem that expressed what sounded like an easy sentiment. The short poems that won large audiences were especially suspect. Granted, I might never have read a poem as lovely as a tree … but poems that talk like that are a very good reason for preferring the tree. Case closed.

I have since warmed to Mary Oliver and appreciate her more than I used to. It is nice to read a poet whose sense of things is not entirely guided or determined by “civilization as it exists at present.” Simple is not the synonym for easy, and simplicity is not incompatible with complexity or difficulty. A few bars of Mozart will suffice to restore that common sense. I do not see in Oliver’s poems a feel-good nostalgic yearning for a simple life, nor an escape from the difficulties of our civilization. Her poems do, however, deal with elemental things. Like the earth rise image, each of her poems feels like some variation of a memento viveri. And it is a life within and among that draws her attention to the things of the word. Here is the conclusion of “Wild Geese,” probably her most famous poem and one of the finest poems on the subject (which is not geese):

| Whoever you are, no matter how lonely, |

| the world offers itself to your imagination, |

| calls to you like the wild geese, harsh and exciting – |

| over and over announcing your place |

| in the family of things. |

To my knowledge, Oliver did not write about gardening or homesteading or practice either. And yet it somehow feels appropriate to say a few words about her here. Oliver, it seems, was more of a forager and a browser than a home-body cultivator type. She was a lover of the wild, a walker in the woods. She once said that the trauma of an abusive childhood at home caused her to abhor houses and enclosed spaces and made her want to spend most of her time wandering outside. Nevertheless, throughout her work there is a keen and fully attentive sense of place that makes her version of the open wild feel like home. “These are the woods you love, / where the secret name / of every death is life again.” What a timely thought for the dead of winter, both simple and true.

Thank you, Mary, for these and other memorable lines that resonate for so many readers at all times of the year. This reader will think of you when March comes and he is out walking at the south end of Canadice Lake and begins to see the skunk cabbage, those earliest harbingers of Spring, rising up from under the blanket of snow with their small pockets of warmth radiating outward, while the “ferns, leaves, flowers, the last subtle / refinements, elegant and easeful, wait / to rise and flourish.” And in the meantime, the seed catalogs that sit in a stack near my wood stove and offer themselves to my imagination at this time of year also offer visions in full color of the rising and flourishing to come.