Not just another day in court

by D.E. Bentley –

There has been significant recent media coverage regarding relationships between citizens –especially youth – and law enforcement. There is a perception, warranted in many circumstances, that law enforcement and the criminal justice system – including the judicial system – is an unfair and unjust system. Yet a system of government, including a system of judicial oversight, seems a crucial component of a civil society. Reflecting back to the 16th century, philosopher Thomas Hobbes in Leviathan offered up his cynical sentiment on human nature by describing the natural state of mankind (the state pertaining before a central government is formed) as a “warre of every man against every man”. The absence of government, Hobbes believed, resulted in a state where the life of man[kind], [was] solitary, poore, nasty, brutish, and short.”

Although most people agree that laws are an important component of a civil society there is much debate as to how much influence government should have in our lives. Differences in beliefs often lead to heated discussions and in some cases violence. Gun control has taken center stage as the most recent “hot-button” issue around how much government is too much, or too little, government. Recent peaceful protests, including growing youth protests in the wake of the tragic shooting at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Florida on February 14, 2018 – which resulted in the death of seventeen people – seem to signal a turning point in youth involvement, in change.

Taking an active role in protests is one way to get involved, but there are many other ways for young people to take active roles in society. The Ontario County Youth Court

(OCYC), a youth ran alternative to mainstream courts and school-based disciplinary systems, offers area youth another avenue for involvement in their communities. Volunteer youth court members have the opportunity to work for the betterment of their communities, while increasing their knowledge of the justice system and their understanding of the underlying reasons for criminal behavior. Using a restorative approach to addressing behaviors, youth court volunteers also provide the opportunity for eligible young defendants to have their cases heard at a peer-reviewed court hearing – by a bona fide jury of their peers.

I recently met with some of the program’s staff and sat in on a youth court hearing for a local youth defendant to gain insight about the program and its participants. Ontario County Youth Court serves youth at courts in Bristol, Canandaigua, Geneva and Victor townships, and, on the surface, is structured in much the same way as a traditional court. There is a judge that presides over the case from the bench; there is a defendant and a defense attorney acting on behalf of the accused. There is a prosecutor serving on behalf of New York State, a jury listening to the arguments and a bailiff to keep the courtroom operating in an orderly fashion. As with more traditional courts, there are opening statements, witnesses called to testify and jury deliberation. There is also the opportunity for involvement in professional organizations: Ontario County Youth Court is a member of the New York State Association of Youth Courts.

The transitioning of courts into instruments of change and rehabilitation extends all the way back to Italian philosopher and economist Cesare Beccaria (1738-1794) – perhaps earlier. Beccaria’s influential theses Of Crimes and Punishment had a lasting influence on how humanity looks at the rights and plight of accused individuals. Published when he was twenty-six, in Of Crimes and Punishment Beccaria called for more humane and just treatment of those arrested, and focused attention on rehabilitation of the condemned. His philosophy is often summarized in a single quote, “’ In order that every punishment may not be an act of violence, committed by one man or by many against a single individual, it ought to be above all things public, speedy, necessary, the least possible in the given circumstances, proportioned to its crime, dictated by the laws.” Such ideas were subsequently integrated into legal codes around the world, including in the United States.

Restorative justice moves beyond Beccaria’s ideas. Rather than seeking to simply punish and “fix” or rehabilitate the individual who committed the crime, the approach encompasses the accused, the victims and society as a whole while emphasizing personal accountability. When feasible, victims and offenders work together to mediate restitution – allowing all to move beyond the crime. Youth courts are part of a growing movement toward restorative vs. retributive systems of consequences.

Making a difference in the lives of youth using a restorative justice approach is the primary objective of the Ontario County Youth Court and this focus was evident during my initial meeting with Program Director Yvonne Vazquez and Outreach Specialist Ian Krager. This is accomplished, Vasquez believes, by “addressing the specific needs of every defendant that walks in the door.” OCYC Staff members Vasquez, Krager and Program Coordinator Brandon Bryant facilitate the daily operations of the program by taking referrals, preparing case files, working with guardians and referral agencies and providing training for youth volunteers. Staff and court volunteers work together as equals. Krager understands this: prior to taking on his current role as Outreach Specialist, he served for more than four years as an OCYC volunteer, including one and a half years as the Chair of the Steering Committee.

Unlike a traditional court system, youth court participants do not decide guilt or innocence. Defendants are accepted, in part, based on prior admissions of guilt – the first step toward accountability. The Court’s role is to examine the circumstances around the offense and decide on appropriate sentencing that benefits the community and the defendant. The advantages of peer review and youth courts’ restorative formats for defendants is the opportunity to be heard by peers, people from their own generation who may have had similar experiences in society – all of us were young people, but not here and now. There is also a greater potential benefit to society – via reduced recidivism rates.

Youth court is not just a court serving youth defendants. It is made up entirely of youth, judging and defending their peers in the hopes of making a difference in the lives of those involved, and in their communities. This difference was evident as I watched the jury assemble, prior to the start of court. Seated along the far side of the courtroom at Canandaigua Town Court, they looked like many other young people. Some chatted and many – as can be expected from this generation – were all thumbs with their cell phones. As I walked around and talked with some of the youth prior to the start of court, the extent of the benefit on all involved youth became more evident. The defendant had not yet arrived and Prosecutor Henry Livingston – who told me that his role was to seek a “restorative outcome beneficial to society” – and Defense Attorney Celia Rivera – focused “on understanding and building on the strengths of the Defendant” – sat poring through case files. The Judge – Elizabeth Maczynski – was also reviewing the case as the Bailiff, Hannah Henry, waited to initiate the proceedings. Court roles are taken on voluntarily by the citizen volunteers allowing the youth to build on their strengths and gradually gain the confidence required to become more involved. Keeping the roles flexible also allows youth to explore different courtroom responsibilities and to recuse themselves if they know the defendant. In exploring different courtroom roles they gain valuable experience and insight for possible future legal careers.

Once the defendant arrived and the Bailiff called the court to order, it was all business – beginning with the judge making it clear that all courtroom proceedings are to  remain in the courtroom. Opening statements were read and witnesses were called, including the Defendant himself. The hearing was structured around offender accountability. Victim statements are an optional part of the process. Questions were asked about the nature and circumstances of the crime. There were also relevant inquires regarding extenuating circumstances, potential impacts on society and on family – including younger children who might hear about or witness the crime. In contrast to a traditional court where the sentencing and consequences are removed from control of the accused, the Defendant was asked what they believed to be the “ideal sentence for their offense.”

remain in the courtroom. Opening statements were read and witnesses were called, including the Defendant himself. The hearing was structured around offender accountability. Victim statements are an optional part of the process. Questions were asked about the nature and circumstances of the crime. There were also relevant inquires regarding extenuating circumstances, potential impacts on society and on family – including younger children who might hear about or witness the crime. In contrast to a traditional court where the sentencing and consequences are removed from control of the accused, the Defendant was asked what they believed to be the “ideal sentence for their offense.”

It took some time for the Defense and Prosecutor to review testimony and complete their closing statements. Members of the jury, witnesses and the defendant sat quietly, waiting. There was that unsettled feeling that often accompanies such affairs, with the sound of shuffling feet and periodic sighs and throat clearings. After closing statements and sentencing recommendations were read, the jury went to their chambers to deliberate – and returned with their sentence.

Given the nature of a youth court, including the focus of the court on a restorative approach to justice, sentences are limited to educational services – treatment, training and workshops relevant to the offense – and community service. All aspects of the court functioning (beyond intake interviews, scheduling and preparing case documents) are entirely youth facilitated. This includes the final sentencing decision that results from the jury’s deliberation.

Once the sentence was read and the court adjourned, the staff stepped in, arranging follow-up services and restitution with the defendant and his guardian. Within the courtroom there was a return to the pre-court easiness. Jurors talked amicably while some returned to their phones, contacting parents for a ride. In the parking lot outside, a new driver negotiated the parking lot and parents pulled up curbside.

These young people are learning first hand about the legal system in the US at a time when young people are more than ever seeing themselves as agents for social change. Although there have been significant and beneficial changes, we as a people continue to move toward a more just system that focuses on the needs of all. Each generation offers new ideas and opportunities for change. People like Michelle Alexander, an associate professor of law at Ohio State University and civil rights advocate best known for her book The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness, highlight new directions for addressing historical injustices. There are many 21st century voices for change – including an increasing percentage of young people willing to look closer, to see others for their strengths and to take a stance against discrimination and discriminatory practices. A movement toward restorative disciplinary practices is also seeping into the schools, as a means of reducing outdated disciplinary models that alienate and enrage rather than engage struggling students.

As I talked more with the Ontario County Youth Court’s staff and citizen volunteers it became increasingly evident to me that the program’s influence extends well beyond the misdemeanor defendants whose cases are deferred there. It is also an opportunity for the students who become involved to learn about various courtroom roles and procedures, even before they are old enough to serve as jurors in more traditional courts.

For some, such as Ian Krager and Elizabeth Maczynski – who took over as Chair of the Steering Committee at the beginning of 2018, it is about finding a career path and pursuing a passion.

“When I first joined Youth Court 2.5 years ago,” offered Elizabeth Maczynski, “I had no intentions of ever pursuing a career in the field of law. After completing the 20 hours of training, I realized my passion for prosecution. Youth Court is more than a restorative justice program for the youth of our community. It’s an opportunity for members to expand their horizons and find a true passion. Today, I want to pursue a career in corporate law. Without Youth Court, I would have never learned about the importance of the legal system in our society.”

Ian Krager, who has been a member of Ontario County Youth Court since middle school is completing his senior year at Red Jacket High School while working at OCYC part-time. He was recently accepted to the University of Rochester and hopes to enroll as a political science major this fall. Krager believes that one of the greatest rewards of his time at youth court has been seeing offenders referred to the court return after completing their sentences – to take on roles as youth court volunteers, to help other young people.

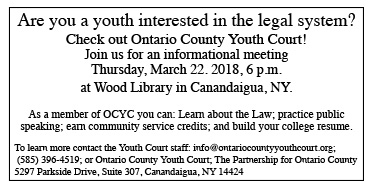

There are many ways for young people to get involved, to take active roles in their communities. For young people in Grades 8-11 from Ontario, Yates, Seneca, and Wayne Counties who are interested in the legal system and in helping to create pathways to judicial and personal change for their peers and their communities, Ontario County Youth Court may be just the thing. The best way for interested youth to get involved is to come to the next informational meeting on Thursday, March 22. 2018 (see left for additional information). Interested youth can also find and fill out an application to become a YC member at tinyurl.com/joinyouthcourt.