Hah-nyah-yah: “Where the Finger Lies”

by Joy Lewis –

Early Years in Richmond: Native Dwellers meet Newcomers.

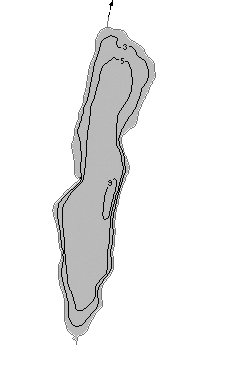

According to legend, the lake called “Honeoye” was given its name as the result of a snakebite. Orsamus H. Marshall (1813-1884), an early settler of Buffalo, wrote extensively in the nineteenth century about the Seneca of western New York collecting indigenous speech and folktales. As he tells it, a native hunter, while out picking wild strawberries at the foot of the lake, was bitten on the finger by a rattlesnake. In a quick reaction he chopped off his finger and left it there on the lakeshore. The spot was henceforth commemorated by him and his comrades as “Hah-nyah-yah,” which Marshall interpreted as meaning “where the finger lies.”

According to legend, the lake called “Honeoye” was given its name as the result of a snakebite. Orsamus H. Marshall (1813-1884), an early settler of Buffalo, wrote extensively in the nineteenth century about the Seneca of western New York collecting indigenous speech and folktales. As he tells it, a native hunter, while out picking wild strawberries at the foot of the lake, was bitten on the finger by a rattlesnake. In a quick reaction he chopped off his finger and left it there on the lakeshore. The spot was henceforth commemorated by him and his comrades as “Hah-nyah-yah,” which Marshall interpreted as meaning “where the finger lies.”

This incident occurred perhaps at about the mid-point of the eighteenth century, for it was around that time that a village at the north end of the lake was established by a small band of Seneca. And so, it was not only the lake, but the natives’ lakeside village as well that was called Hah-nyah-yah. For three or four decades the Indians occupied the site, until the arrival of the Continental soldiers.

During the summer of 1779 General John Sullivan and his American Army marched across the plains and hills of western New York despoiling native territory. From a score of Seneca villages they chased off the inhabitants, laid waste their homes, and destroyed crops and stores. On September 11 the soldiers arrived at the foot of Honeoye Lake where they discovered a deserted Seneca village. The community, home to fewer than a hundred people, consisted of eleven log houses and several acres of corn fields.

“An old Squaw [later reported] that the approach of Sullivan’s army was not discovered by them until [the soldiers] were seen coming over the hill…They were quietly braiding their corn, and boiling their succotash. She said there was a sudden desertion of their village; all took flight and left the invaders an uncontested field…never look[ing] back until [they] reached Buffalo Creek.”

Sullivan’s men set about methodically to annihilate the homes and fields; they put up a rudimentary fortification they dubbed “Fort Cummings.” The next day they marched westward, reaching the head of Conesus Lake by nightfall. From there a scouting party, under the command of Lieutenant Thomas Boyd, set out.

“The little band winded their way through the dense forest by the Indian trail, until they reached the little village of Canaseraga, [present-day Mount Morris], which they found deserted, although the fires were still alive in their huts.” Later they came upon two Indians and one was killed. Fearing for their lives, the scouting party prepared to retrace their steps back to the safety of camp. “Five weary miles had they [traveled] when they were suddenly surrounded by five hundred Indians”

Although Lt. Boyd and his men fought bravely, they were soon overcome. Most of them were killed; one or two managed to escape. But Lt. Boyd and Sgt. Michael Parker were captured. They were taken by the enemy to the vicinity of Beardstown (Cuylerville) where they were handed over to Little Beard and his warriors. Stripped, Lt. Boyd and Sgt. Parker were tied to a tree and systematically tortured to death. Just at evening, as the main body of the Army passed by that way, the mutilated bodies of the two unfortunate men were discovered. “The remains…were buried with military honors, under a wild plum tree, which grew near the junction of two streams.”

Ten years after Sullivan’s foray along Honeoye Lake the township of Richmond (then called Pittstown) was formed. In its first two decades the town was sparsely populated. One of those early incomers was William Boyd (1755-1811), cousin to the unfortunate Lieutenant. William settled in the vicinity of Allen’s Hill, overlooking the lake. He was forty-four years old in 1799, married and the father of six children ranging in age from four to twenty-five. His two eldest children, Sewell and Sarah (Mrs. Lovett Church) were married and both had properties near their parents’ farm.

In the summer of 1802 “a little daughter of…Sewell Boyd, three years old, was lost in the woods. A lively sympathy was created in the neighborhood, the woods were scoured, the outlet waded, and the flood wood removed; on the third day she was found in the woods alive, having some berries in her hand…The musquetoes had preyed upon her until they had caused running sores upon her face and arms, and the little wanderer had passed through a terrific thunderstorm.”

A few years before the Boyds’ arrival in Richmond, had come Jacob Flanders (1756-1841) with his wife and four children. Born in New Hampshire, he served in the Continental Army during the Revolution, a soldier under Sullivan’s command. He staked claim to a property at the head of Honeoye Lake where he built a hewn log house. His neighbors well knew that Jacob “saw the interest attached to anything relative to Sullivan’s expedition and delighted to tell the old settlers of incidents of his own observation. He spoke of the warning cannon shot which struck consternation to the Indians, who scattered in every direction,” on the run from the approaching soldiers.

When twenty-two-year-old William Warner (1772-1850) and his brother Asahel came to West Richmond at about the same time as the Flanders family, they observed that, “Indians were numerous and to a certain extent troublesome.” A few early tales of Indian trouble survive.

One such incident was related by Hiram Pitts (1802-1901) in a letter commemorating Richmond’s Centennial: “[We once had a problem with an Indian] that was caused by rum. In my father’s absence one day, an Indian called at the house and wanted some liquor. My grandfather [Peter Pitts, Richmond’s earliest settler]…told him he could not let him have any, which made him angry, and he drew his knife and attacked him. A sled for hauling wood was at the door, and [Grandfather], although rheumatic, made a hasty retreat around the sled; but being closely pursued, pulled out one of the stakes and with a blow laid [the Indian] senseless on the ground. His squaw then took up the matter and trouble was feared, but fortunately Horatio Jones, the Interpreter for the tribe, arrived and soon settled the difficulty – the Indian soon came to and the squaw was pacified.”

Another incident occurred in a settlement just west of Richmond. James Henderson (1762-1824) settled at the head of Conesus Lake in 1793. A dozen years later he and his wife Jane and their nine children came to Richmond and built a home in Allen’s Hill. While still living in Conesus James was attacked one day by an irate Indian. When he would not give the Indian the liquor he wanted, the Indian threw his tomahawk at James; it grazed the side of his head and embedded itself in the log wall of his home beside the open front door.

Encounters between homesteaders and the Seneca who lived in the area were a common occurrence during the first two decades of settlement. In spite of a few troubling incidents, for the most part these interactions were cordial.

In her old age Hannah Pitts Blackmer (1777-1862) recalled that “the first few years after our family came in, there were many Indians passing our house daily, and hunting parties were encamped nearly all the time in the neighborhood [of the Honeoye Flats]. Mrs. Jemison [the White Woman of the Genesee] used to be at our house frequently, on her journeys from Gardeau to Canandaigua and back.” Hannah’s mother Abigail (wife of Peter Pitts) handed out loaves of bread to her Seneca neighbors on a regular basis.

Hannah’s brother William (1767-1815) married Hannah Taft in Richmond in 1795. In January 1802 William and Hannah’s fourth son was born, and in August Hannah died. Her death was recalled by a friend: “The Indians, if they were guilty of occasional outrage, had some of the finest impulses of the human heart. [Hannah Pitts] who had always been kind to them, was on her death bed; hearing of it, the Squaws came and wailed around the house, with all the intense grief they exhibit when mourning the death of kindred.”

Hugh Hamilton (1770-1851) came to Richmond early in the nineteenth century. About 1810 he became half-owner of the Crooks grist mill. In a family memoir Hugh’s son wrote of those early days: “While father ran the old mill on the creek, all the south and east part of Richmond and West Bristol depended upon it for their grinding.” Whenever there was grain to be ground, at the end of the day the sweepings were given to the Indians living nearby for their porridge.

The years passed and the older generation of Seneca was no more. The younger people gradually migrated away from Richmond, making their home at the Gardeau Flats (in present day Letchworth State Park) and later at the Seneca Reservations of Cattaraugus and Allegany.

(Quotations used in this piece may be found in the following sources: Pioneer History of the Holland Purchase; History of Ontario County, NY, 1788-1876; Letter written by Hiram Pitts, October 4, 1888; Biographical Sketches of Leading Citizens of Livingston and Wyoming Counties, New York; The First Settlers of Conesus, Livingston County, New York: “History of the Town of Conesus.”)