Bog Time – a Journey Back

- D.E. BENTLEY

A rising mist surrounds you as you step out of the time machine onto a massive ice cube, a floating frozen island. Pockets of water—an expanding liquid ring teaming with Microbial life—define the perimeter of a deep circular depression.

As ice cracks beneath your feet, you step hurriedly back into the time machine and whirl forward another 10,000 years. Your ice island has melted into an expansive lake. At the water’s edge, a woolly mammoth mother nuzzles a calf and they drink from the lake. Vast grassland surrounds them. Patches of sphagnum moss cluster on the shoreline; the mosses, too, are thirsty.*

*Sphagnum mosses can hold up to 20 times their own weight in water. ipcc.ie/a-to-z-peatlands/sphagnum-moss-the-bog-builder

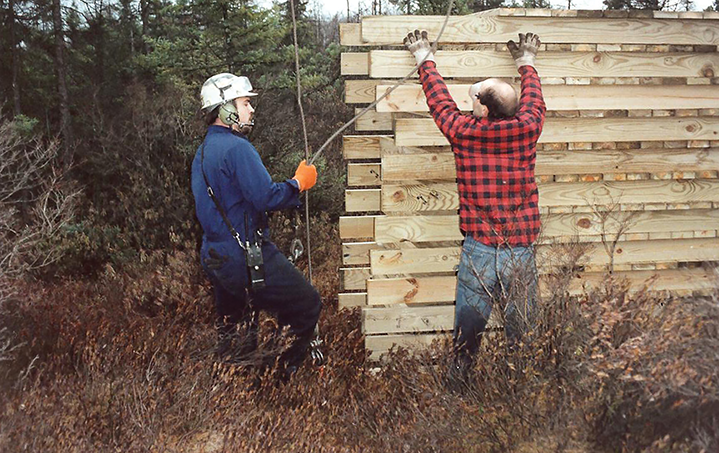

Time spins wildly behind you and the whirl of the time machine is gradually replaced by the hum of a helicopter hovering just overhead. It circles around and drops a bundle of lumber to a group of people waiting below before lifting off and reloading for a return trip. The dropped materials are the first sections of a floating walkway that now loops 1500’ into the bog’s interior, offering visitors safe access to the bog while protecting the rare and delicate landscape that depends on this unique ecosystem for its very survival.

The island of ice has—over thousands of years—transitioned, first, into a living lake, which has now, through eutrophication, become a fifty or more feet deep floating island of decomposed plant materials—mostly peat moss. You reach out to a nearby sapling for support as you step out on to what you believed was solid ground; it gives way beneath your feet as you balance precariously on a living, floating island.

It is 1979 CE, and the once-upon-a-time remnants of the last ice age have vanished. The Bog bears little resemblance to the earlier watery time or the times that followed, when there was an abundance of grassland for the mammoths. A small forest of black spruce seedlings is interspersed with cranberry bushes (the bog’s namesake) and carnivorous and other flowering plants. Layers upon layers upon layers of the past are visible for all who visit.

Fast forward to April 1, 2022, when my time machine (a Tacoma 4X4) leaves me in a parking lot next to an informational billboard. I have arrived at Tannersville Cranberry Bog in Monroe County Pennsylvania, one of only two late-succession boreal ‘kettle’ bogs in the state. I found Tannersville Bog while searching for a day hike, during a ten day spring trip to Pennsylvania for a Search and Rescue (SAR) training. Having grown up in the Finger Lakes, surrounded by the tall falls and deep gorges carved by the retreat of our last ice age—and further inspired by bog visits in Scotland in 2018—this glacial wonder drew me closer (as it has done for so many of those who have cherished and protected it through the years).

The Bog was just minutes from my lodging (and a stone’s throw from a gated community, one of many such developments that are encroaching on and threatening the wildlands of northeastern Pennsylvania—more about that in afterthoughts). I drove to the site on April 1st and, after a series of phone calls to Monroe County Conservation Districts’ Kettle Creek Environmental Education Center (Kettle Creek)—the bog and community’s educational stewards—I received permission and strolled along Cranberry Creek through a shady, peaceful grove of ferns and moss-blanketed roots to the beginning of the boardwalk.

Cranberry Bog, one of The Nature Conservancy’s (TNC) first preserves in Pennsylvania, is the southernmost low-altitude boreal bog on the Eastern Seaboard (similar bogs can be found in the Adirondacks of New York, and in the Canadian wilderness). The early acquisition and preservation of the “Cranberry” (as it is sometimes affectionately called) was made possible by Professor William A. Niering (1924 – 1999). Niering, born in Scotrun, a small town in the Poconos, was a well know biologist and Lucretia L. Allyn Professor of Botany at Connecticut College. He initiated the purchase of the first 63 acres of the Tannersville Cranberry bog near his home in the Poconos, one of many concerned citizens who stepped in to make the initial and later acquisitions possible.

Another name that kept coming up was that of Jim Ross, the 5th president of TNC (1958-1959). Ross, a local publisher (Dowden, Hutchinson, and Ross) was also an early member of the bog committee, and, as president of the Nature Conservancy when the Bog was acquired, was influential in helping to secure funds for the boardwalk and additional buffer lands to protect the Bog.

On the day I first visited the Bog, a group of TNC workers and volunteers were on site, working on the second phase of a preservation project. I spoke with Josephine Gingerich,* who was overseeing the volunteer work as TNC’s Land Steward in Pennsylvania. She explained that the current work being done involved clearing an area in the center of the bog’s boardwalk.

*Gingerich was with TNC for 5 years; she left to pursue exciting new adventures soon after we met in late March.

The goal of the planned clearing is to increase habitat for endangered native plant species, including cranberries, the bog’s namesake, and to encourage the re-establishment of plant species unique to the bog—some of which have not been seen for decades. An earlier clearing initiative, in 2012, Gingerich explained, had proved successful—resulting in an increase in endangered flowering bog plants—and was now being expanded. I walked the boardwalk and took photographs while brush was moved to a chipping site above the bog. Some of the clearing that was taking place was to remove invasive species, not native to the original bog ecosystem, and to replicate clearing that might have occurred due to naturally-occurring fires.

After a loop along the bog’s boardwalk and some quiet time listening to the gentle water voices rising from the bog’s platform overlooking the meandering Cranberry Creek, I headed back toward the parking area and encountered a bog walker named David Buck. David, I discovered as our conversation evolved, is a bog enthusiast who was involved in the earliest phase of construction of the floating pathway that expands educational outreach in the bog—while safeguarding visitors and the delicate ecosystem that sustains the bog’s most vulnerable and important inhabitants. Due to David’s past involvement and extensive bog-related knowledge, my initial foray into Cranberry Bog—like the moss that gradually sucked up the lake that was—has expanded and grown.

I learned more about the boardwalk in late May, when David visited us in Canadice, NY and shared a video of the boardwalk being dropped into the bog by helicopter—section by section. The video also included an early educational walk through the bog, led by Don Miller. I learned more during a subsequent phone interview with Don Miller, who worked as Head Naturalist/Conservation Education Director at Meesing Nature Center, part of the Monroe County Conservation District (MCCD), from 1977 to 1984, during the period when the first 100’ of the boardwalk was installed. Miller elaborated on the boardwalk, which is supported by the Follansbee Company floating dock system drums. At the time of the initial installation, the Follansbee Docks* was a new dock system company in West Virginia with military contracts and the use of their drums at the Bog was one of the first non-military uses of this new lightweight air filled ABS plastic drum system.

*marinadockage.com/buyers_guide/follansbee-dock-systems

The wood walkway is made of pressure treated lumber and, given the potential hazards inherent with this type of wood treatment, two years of water testing* was required following the installation, to assess the potential impacts before TNC would give the go-ahead for the remaining sections. Don recalled helping cut rectangular holes in the bog mat in winter for the floating drums (an improved design—now filled with foam for better buoyancy). David, Don shared, was instrumental in making all this happen, with the support of a very active (monthly) local Bog Committee (established in 1977). Working with the County Commissioners, they were able to get the Monroe County Vo-tech School to build the 10’ long decking sections. The sections were then stockpiled in the Bryson sisters field, adjacent to the Bog. In the end, the remaining sections were also approved and added. The educational access and outreach made possible through the boardwalk is a defining characteristic that differentiates the Cranberry Bog from TNCs original emphasis on land preservation.

*Testing was donated by Prosser Labs.

“Once a bog enthusiast always a bog enthusiast” soon became my mantra as David introduced me to a widening circle of bog-loving conservationists. The importance of education as part of the Bog preservation mission was evident among all who I spoke with, including Roger Spotts, the Monroe County Conservation District’s Environmental Education Coordinator since 1984. Spotts manages the bog’s educational programs, land stewardship, and acquisition efforts. In addition to regularly scheduled walks open to the general public, MCCD has facilitated nature walks there for thousands of Monroe County (PA) elementary school children over the years. Due to that educational object and the collective work to make the bog more accessible to all, four thousand people a year are able to tour the bog.

This educational focus came even more into view when, on June 1st, Todd Touris and I were invited into the bog to join a who’s-who group of early bog enthusiasts: Dr. Ray Milewski, a botanist and retired East Stroudsburg University professor—who was influential in the restoration initiative and is also the current chair of the Tannersville Cranberry Bog Stewardship Committee; Rob Baxter, a long-time realtor and environmental activist involved with the bog for 40+ years; Melody Buck, a botany student of Frank Buser, who assumed an active early role in the bog—including helping with the earliest boardwalk installation; Don Miller, who first visited the Bog as an East Stroudsburg University (ESU) student with Professor Frank Buser in a Summer Botany course in 1972 and has, over the past 45 years, led many other walks into the Bog; and David, our host, a former chairman of the bog’s preservation committee and lifelong bog-enthusiast.

We were treated to a delightful educational experience as we listened to these co-boggers reflect on the Bog’s educational roots and on the geological roots that created such a magical place. My head was spinning as the group’s members shared their vast knowledge of the flora and fauna unique to, and dependent upon, the Bog’s delicate ecosystem.

Cranberry Bog’s water is replenished through precipitation alone. Ombrotrophic bogs have few nutrients, which greatly limits plant diversity and slows growth. Carnivorous plants, such as sundews and pitcher plants, have adapted to the nutrient deficiency by trapping insects and dissolving them for nutrients. Invasive bushes, such as Japanese barberry, English privet, multiflora rose, highbush blueberry, sheep laurel, and leatherleaf, as well as stilt grass, have also adapted to the bog environment. As they take a greater foothold, their presence threatens some of the native plant species.

The desire to turn back time and restore the Bog to earlier periods in its succession have prompted the more active management approach evident during my initial bog visit. Roger Spotts cited the success of the trial clearings in 2012, when Dr. Ray Milewski and students from East Stroudsburg University established several small study plots at the preserve. Their research suggests that removing woody, shade producing vegetation allows rare bog plants to reestablish themselves. These study plots are the basis for expanded cutting to create a larger clearing in the center of the boardwalk. The clearing involves the removal of invasive species by hand.

Ray Milewski shared with us additional insight into the scientific hypotheses that he and his students followed and used in the original managed clearings:

“Over the years as shrubs have come to dominate the bog community, various distinctive bog plant species have become reduced in numbers or have disappeared from the community. A theoretical framework for managing of plant communities developed by European researchers, for example Grime, reduces dominance by increasing disturbance. Because of the small seed strategies found among plants in field communities, disturbance results in weedy species becoming established. In comparison, though, the reproductive strategies of plants in bog communities is one of persistent propagules which can germinate many years later. More than 12 years ago I set up a research project in the bog in which shrubs and trees were removed from one area. Afterwards we saw the establishment of populations of open sphagnum mat species such as bog rosemary and cranberry in this plot. This year we saw the blooming of decent sized populations of two bog orchids, the grass pink and rose pogonia in this research area. Grass pink orchids have not been seen in this particular bog since at least the 1950s. It is heartening to see how successful this management project has turned out.”

Click here to see images of grass pink and rose pogonia orchids by Photographer Ray Roper.

The clearing also includes the removal of some black spruce and tamarack trees, growing at the southern limit of their ranges. Although the spruce trees being removed are only around 4” in diameter and a mere 15-20 feet in height, some are more than fifty years old. The black spruce were seedlings in the seventies when the earliest members of the Bog Stewardship Committee put the boardwalk in place. Some early bog preservationists, including David Miller—although in agreement on the need to clear out woody invasives—question the need to remove the trees as well. Nonetheless, David was on hand, helping with the clearing (and encouraging me to join in as well).

(See “Heartwood”by Todd Touris to learn about his creative “cookies”, made from black spruce from the bog.)

Based on the results of the earlier test plots, the clearing will offer space and light for the continued reestablishment of orchids, bog rosemary, and carnivorous sundew and pitcher plants. It also benefits the bog’s cranberry plants, which, in turn, benefits the Bog Copper butterfly (Lycaena epixanthe) that feeds almost exclusively on the native cranberries. The Bog Copper is a Pennsylvania species of concern, with a state ranking of S2 (imperiled).*

*The Bog Copper are given this name because their coloration ranges from orange-red to brown, usually with a copper tinge and dark markings. The Bog Copper is the smallest of the United States coppers and is found throughout northeastern North America. This species is restricted to acid bogs with cranberries (Vaccinium macrocarpon and V. oxycoccos). The bog substrate, usually Sphagnum moss, must be saturated or nearly so most or all of the year and the area must be sunny.

After our walk, we settled in for continuing conversation at Cook’s Corners Family Restaurant in nearby Henryville. The group would have rather gathered at the Tannersville Inn. It was at this 100-year-old Inn that the earliest members of the Tannersville Cranberry Bog Stewardship Committee and other co-collaborators met to share their love of the Bog and plan for its future preservation and educational accessibility. Now permanently closed, Tannersville Inn is slated to be razed and Wawa (an East Coast convenience store chain) wants to build a convenience store on the site. David took us by the Inn, on our way to the bog. For the five individuals who led us into the Bog, the bog walk was a reunion, a chance to reflect back on times past. For me, it was a chance to take a closer look, to let the Bog weave its magic on me as it has with so many who came before. The stop at Cook’s Corners also gave me the opportunity to sample shoofly pie (a marvelous, delicious concoction of molasses that is, I was told, as old as the Pennsylvania hills).

Understanding the past helps inform and safeguard the future. Science, combined with human imagination, offers us all opportunities to explore more and to collectively safeguard and build a better tomorrow. While stopped along the boardwalk, we were alerted to a corner area where scientists have taken 10’ core samples of bog layers. These are being analyzed for clues, including pollen analysis, to gain a better understanding of how the flora has evolved over time and for insight into the human impact on flora. Concern for and action on behalf of our environment begins with scientific curiosity and interaction with the natural world. Our understanding of humanity’s role in environmental degradation and our active responses to environmental challenges has evolved in much the same way that bogs change, slowly, and incrementally. It was the establishment of the Union of Concerned Scientists in 1969 that offered a stepping stone for the development of The Nature Conservancy, which has, according to its website (nature.org) “protected more than 125 million acres of land.” Many other national and regional organizations also take active roles in preserving what remains. Humans have accelerated extinction around the globe and increasing numbers of individuals believe that we have entered a new age: the Anthropocene or “Age of Humans.”* That is, an age when human-induced impacts have permanently altered our world (and possibly our geological record, what future humans will discover as they, in turn, dig up and explore the past).

*First mentioned by Nobel Prize-winning, atmospheric chemist Paul Crutzen and biologist Eugene Stoermer. Possible affirming signals of human influence include things like plutonium, concrete, plastic, nitrogen, fly ash, and carbon isotopes. (smithsonianmag.com/science-nature/where-world-anthropocene-180960241/)

Don Miller begins his informative foray, often, with:

“In just 1000’ of a “dry foot” walk all who visit are transported back 10-15,000 years in time as the glaciers carved out and then retreated from Monroe County in the Poconos of Pennsylvania to create this landscape. And you are also transported several hundred miles north to similar Bog wetland landscapes of the Canadian Maritime provinces.”

His words offer an introduction to a very special ecosystem that is being actively managed to maintain a diversity of species. For the immediate future, Tannersville Cranberry Bog will continue to educate people of all ages and cement in them (as it has for all those who shared their stories of this magical place) a love of and appreciation for the natural world.

If we were able to climb aboard our time machine and travel thousands of years forward in time we would see (given the natural progression of succession and void of human intervention) a forested world—perhaps one with new flora and fauna adapted to a human-influenced environment. The near future of the Bog will be determined by today’s and tomorrow’s bog enthusiasts and preservationists. The educational mission that has been established at Tannersville Cranberry Bog increases the chances that future generations will value and set aside even more land for those yet to come.

As Don Miller puts it: “I still to this day run into former students, now in their 40s and 50s, who remember and talk about their first visit to the Bog in Tannersville. I think the unique Bog and it’s well-trod floating boardwalk did in fact work its ‘memory magic.’ And those who before us took wet footed students into the Bog, I believe are smiling down on our boardwalk efforts and accomplishments.”

Afterthoughts

A follow up conversation with Don Miller and David Buck offered a greater understanding of how development in PA, as in many regions of NYS, threatens natural areas. There was considerable new housing development visible near where I was staying, minutes from the Bog. I asked Don, who in addition to his educational role at TCB has been on the board of the Pocono Heritage Land Trust (phlt.org) since its founding in 1984 and on the board of the Brodhead Watershed Association since 1991, to elaborate on current challenges in the Delaware Valley region of PA. As a New York resident who spoke out against fracking and attended related public meetings, I recalled how the impact in Pennsylvania was often cited in public discussions. In the southern parts of Pennsylvania, I had passed rigging areas and encountered heavy truck traffic associated with fracking, but, according to Don and David, fracking is not a direct risk in the Delaware Valley. The only possible (direct regional) concern is the possibility of waste water being shipped to smaller municipalities in Pennsylvania (and New York) for processing, including sites in the Delaware Valley that are being looked at for disposal.

Don cited the big box distribution industry and housing development as the greatest risks to natural areas in the Poconos. The Interstates have enabled the development of major industrial hubs as rural areas zoned commercial without the expectation of development have, in some instances, miscalculated the potential impact of big box distribution and large-scale housing development. In a May 5, 2022 posting, the Supply Chain Digest cited a report from Colliers that defined a big box distribution center as a distribution center (DC) over 200,000 square feet. Companies like Amazon, Walmart, Gamestop, Chewy, and UPS currently have DCs in Pennsylvania (or have plans for them). Some of these centers are more than a million square feet in space.

The increased impervious surfaces from massive parking lots and access roads (coupled with a lack of regulation due to their status as private) results in higher chlorides from road salts that can threaten wetlands and residential wells (how most people in PA get their drinking water). Grits are less effective in PA due to extreme freeze/thaw cycles and these carry their own risks (including potential heavy metals found in some recycled anti-skid materials).

As metropolitan areas become more populated, populations will continue to move outward and forested areas (and wetlands) will be threatened. Newer initiatives, such as the Our Pocono Waters (OPW) , which educates the community on the importance of protecting “Exceptional Value” (EV) streams,* are part of a growing preservation movement.

*While only 2% of Pennsylvania streams are classified “Exceptional Value,” 80% are located in the Poconos, primarily within Monroe, Pike and Wayne counties.

Visiting the Bog

The Boardwalk Trail is accessible by guided tour only*

(dogs are not allowed on the boardwalk trail).

For additional information about regularly scheduled Bog walks contact the Bog’s stewards at:

Kettle Creek Environmental Education Center, 570-629-3061.

Additional information about restoration projects and a schedule of upcoming tours can also be found at: nature.org/en-us/get-involved/how-to-help/places-we-protect/tannersville-cranberry- bog-preserve/

*There are two Public Trails – the North Wood Trail and the Fern Ridge Trail – that are accessible anytime (dogs are allowed on leash).