Tin Can Optimists

- ANNE RUFLIN –

I have no idea what they were thinking, or perhaps thinking had nothing to do with it. Maybe Dad, just past his 40th birthday, was having a sort of midlife crisis— craving an adventure beyond tedious business trips between Rochester Products and the GM factory in Detroit.

Maybe Mom, having spent a significant part of the past decade either pregnant, giving birth, recovering from childbirth, or attempting to civilize the five wild beings she had birthed, was simply exhausted and willing to do anything to get out.

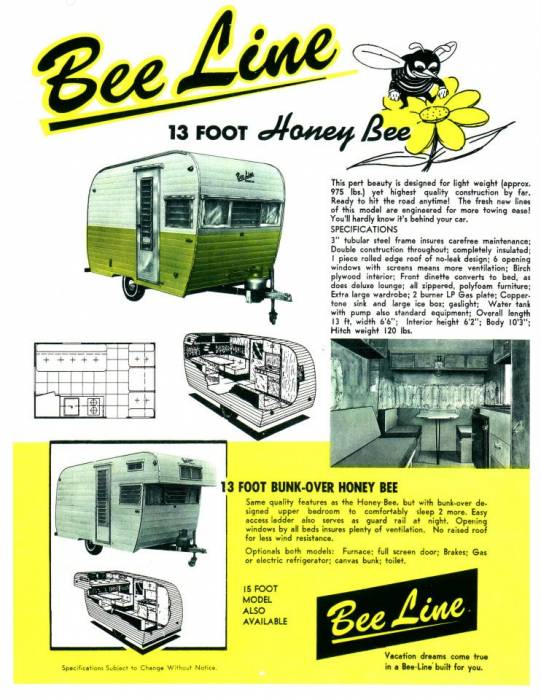

Perhaps the brochure Dad picked up on his way home from work for the rental of a 1965 Bee Line 13-foot Hornet Travel Trailer is what hooked them: “Make a BeeLine Escape” and “Leave Home and Like It!”

And so, it was done. The trailer was rented for the last week of June, just after school let out and before peak summer prices. Our campsite on the shore of Lake Ontario was reserved. Our first family vacation was about to happen! We were going to be real Tin Can Tourists!

My parents, elated at the prospect of finally getting away and certain of the wonderful memories they would create, delved into planning the trip with gusto. Using a combination of welding, wiring, and the ever-ubiquitous duct tape, Dad rigged up our cherry-red Chevy station wagon with a trailer hitch. Mom masterminded filling her allotted 180 square feet with enough food, clothing, toiletries, towels, toys, and accessories to sustain our family of seven for a week – since once there, she would have no access to shopping or laundry. Her packing consumed our dining room table for days. Under no circumstances were any of us kids to add to or take away from the sacred packing pile. Even the cat knew better than to touch it.

On the designated Saturday morning, Dad went and picked up the camper while Mom lined us up for post breakfast inspection. Teeth brushed? Check. Hair combed? Check. Bags packed? Check. Dad rolled in. We kids stood back. This was not a time to offer help. Instead, we watched, observing Mom’s skills in “making do” and Dad’s engineering brilliance as they stuffed the camper and car to the brim. Even baby Joan’s full-sized highchair and stroller were tucked in someplace. Finally, we could get in and go! Seatbelts and car seats were not a thing back then, so we kids just crammed into any open nook available, including on top of baggage or each other’s laps. We could have been the promotional poster for Ralph Nader’s newly published book Unsafe at Any Speed. That just added to the excitement.

Fully loaded and hooked up, the car sagged and the engine coughed as Dad put it into gear. Mom’s hand went to her mouth. Was it too much? But the groaning did not worry Dad any more than the prospect of being confined with his bustling family in a 13-foot trailer for a week. We were off!

The little camper was meant to be a step up from a tent and promised to sleep up to four people. This limit did not deter my parents with their family of seven. Baby Joan was not quite a year old, and Dad expertly wedged a wood slat across the opening of an upper shelf to create sort of a “cubby crib”.

The dinette turned into a small bed that could sleep my brother Scott and I, ages 4 and 5. There was a bench seat that jackknifed into something almost the size of a twin bed, which my parents decided could fit them both if they slept head to foot instead of side by side. Sleeping bags and air mattresses were brought along so my brothers, Tom and Mike, ages 9 and 10, could sleep in the back of the station wagon. While leaving your young sons to sleep unattended in the back of a car would get you arrested today, in 1965 that was no problem.

I’m sure my parents imagined we would simply spend hours at the beach or playing in the woods, a fun outdoors adventure. We wouldn’t even notice the small, cramped quarters of the camper, because we would rarely be in it. But Mother Nature did not cooperate. On our first walk to the beach, wind blew hard and sand quickly filled our shoes, our hair, our eyes, our mouths, and our clothes. Tiny pebbles stung our legs and made us cry. It was too cold and wavy and windy to swim, so we hung around the campsite, slapping and swatting at the relentless black flies and mosquitos and playing in the dirt. Within hours we were all filthy and bug bitten, and we stayed that way for the duration of the trip.

Mom sprayed our campsite so often with a giant can of bug spray, that we ate, slept, and played under a persistent cloud of DEET. It stayed unseasonably cold. Dad tried to cheer us with campfires, but the campsite wood was damp and green and refused to burn hot, even when doused with lighter fluid. Our eyes burned with toxic smoke; our marshmallows barely toasted. Our woodland adventures were limited to trips to the bathhouse—following a muddy and root-filled footpath to a low cinderblock building where snails lived in the showers and some sort of mold inhabited the toilets. None of us dared ask what made the floor so slick.

The two younger kids did their fair share of crying and whining at the discomfort of it all. The three of us old enough to complain did that, too. I complained—with the fault-finding particular to age five—about the risky nature of putting baby Joan on a shelf, that Scott kept finding dead things to poke at with a stick on the road, and about sleeping on a bed that was really a table.

Mike and Tom complained—with the tumbling ferocity particular to young boys—about the horrors and grave discomforts of sleeping in the back of the car. Finally, Mom and Dad traded places with them. And the next morning Mom and Dad agreed with the boys’ initial assessments. The shadows and sounds of the night woods were creepy. The car was not level and there was no way to get comfortable in it. Still, the slanted back of the creepy station wagon was better than the jackknifed camper bench bed, so Mom and Dad slept in the car the rest of the week, leaving us five kids in the Beeline.

By the end of the week none of us was speaking or crying anymore. Dad was smoking double his normal number of cigarettes. Mom’s lips had compressed into a stoic line. There was no use in complaining. We had settled into life as tin can refugees, sullen and silent.

As we packed up and pulled out, Mom broke the silence. “Won’t it feel nice to be in our own beds?” Dad laughed, “yes, sometimes the best part of a trip is how great it feels when it’s over.”

Although that was to be our one and only camper trip, having a summer adventure the last week of June became a family tradition. Year after year my parents would find another trip of a lifetime, and year after year their tin can optimism remained unspoiled—full of humor, adventure, and resilience. Eventually we kids learned to open it up, take a heaping spoonful, and savor it.

Photos by Gerard Ruflin

Anne Ruflin is an emerging author, a retiree, and a member of the Bristol Library memoir group Bristol Bookends 2. When not obsessing over her next writing assignment, Anne enjoys horseback riding, dog walking, and eating chocolate. She lives in the Bristol Hills with her husband, horses, dogs, and cat. Her story Summer in Your Veins (about her father, Gerard Ruflin) was published in Owl Light Literary: Turning Points – 2021.

2 thoughts on “Tin Can Optimists”

Comments are closed.

Love this story!!!

Me too! Has me looking for a camper…a small one.