On Trees and Transience

- DERRICK GENTRY –

All

Things

Must

Pass

In Fond Memory of Sam Hall

Is it not a maimed and imperfect Nature that I am conversant with? I am reminded that this my life in nature … is lamentably incomplete.”

– Henry David Thoreau

A brush pile, from a bird’s point of view,

is surely a poor substitute for standing tree.

Rising at most five or six feet off the ground, far below the lofty heights of a leafed-out canopy, a modest-sized piling up of branches nevertheless offers hundreds of linear feet of perching real estate and forms a dense thicket of protection from earthbound predators (such as my outdoor roaming cat). Perhaps the juncos act a bit more on edge down this low to the ground; they disperse in a flurry of panic every time I approach. With every passing week of their winter residency, though, they seem a little more comfortable with my presence, remaining perched for longer as I trudge through the snow on my well-worn path to the woods.

The brush piles distributed about my property are, without exception, popular and noisy gathering places for the avian demographic. In fact, I often see more birds down low in brush piles than perched up on high in the branches of living trees. So I could be wrong: these piles may be a preferred habitat, and not a down-market compromise.

The chickadees, famous for their long-term memory, will not be able to return to these remembered places next winter. Or at least not to the exact same spots. Even the tallest of brush piles shrink down in size more rapidly than one might expect. In any case, I have Springtime plans to convert these small-diameter branches, with their high cambium to cellulose ratio, into ramial wood chip mulch to feed the fungal-dominated soil around my young apple trees. In the meantime, and for as long as possible, these piles are for the birds: left here intentionally to provide a useful habitat, and – I must add – fashioned with good intent as a feeble offering to atone for the brush piler’s troubled conscience.

For I cannot tell a lie about the source of this woody debris. Here, for example, rising up like a massive funeral pyre, lie the remains of the oldest, most majestic, most beautifully proportioned tree that I have thus far cut down this winter. It had put on one last spectacular show of Fall leaves only a few months ago. But like most other ash trees in the vicinity, this one had telltale signs of senescence: More and more branches in the crown bare of leaves; the “D”-shaped holes in the bark indicating where the emerald ash borer larvae have made their exit once their damage has been done; and, even more visible, the pockmarks and flayed strips made by the woodpeckers who have a sure sense for when a tree is on its way out.

Taking down such a large tree, one that still puts on leaves and shows some vital signs, is a morally ambiguous task. I had been postponing this particular item on the agenda for some time. One frigid and quiet morning in February, I decided I could put it off no longer.

There is nothing quite like the sound of a large tree being felled in the dead of winter. The downed tree always makes a much louder impact than expected, then followed by a brief but violent flutter of branches that is nothing like the sound they make when agitated on a windy day. And then there is the almost sublime period of silence that follows, intensified by the crisp cold air and the thick blanket of sound-dampening snow that lies on the ground. Finally, a moment of silent contemplation. In a matter of seconds, the better part of a century’s steady growth has come to an abrupt end, a massive and imposing presence converted into one to two face cords in a short afternoon’s work, all of which provides less than a month’s heat for a small household.

In normal times, taking down trees in the winter feels a bit more like a regular “pruning” of the woods, the making of minor edits here and there to an established woodland ecosystem. We tell ourselves stories to help us make sense of, or in some cases rationalize, the normal practice of woodland management: We are opening up the canopy, letting in more light for new growth while harvesting fuelwood in the process, judiciously removing invasive species. Sometimes, the felling of a tree for firewood is simply a matter of fortuitous natural

selection – trees blown down by the wind, or trees that have succumbed to disease or simply died of old age and natural causes. It is all good, healthy, low-impact intervention.

These past several seasons have not been normal ones for people living in wooded areas east of the Mississippi. In many places where the white ash grows, woodland management can feel and look more like clear cutting. Sometimes there is not much left behind. Once the ash is removed, we realize that our woodland was not quite as biodiverse and resilient as we thought. We have all had to look for a different story these past few seasons, suddenly made to play the role of landscape designers and charged with making thorough revisions rather than minor edits. Rather than managing wooded land, our thoughts now turn to the weightier question of how to recreate a healthy woodland ecosystem.

Spring in any year is a time for atonement and renewal, for thinking about the future and giving back what was taken. I have spent much of this winter thinking about regenerative plans for the post-ash era, and how to be the best possible steward for my own wooded property. My homework has involved considering which tree species to plant and where, along with various other factors such as longevity and diversity, aesthetics and functionality, my needs and the needs of other creatures who live alongside me in this ecosystem (including the birds, of course). And I am thinking both about trees that I want to be there long after my four score years, as well as trees that will not be standing nearly as long and with which I will have a different but no less meaningful relationship. Above all else, I have been thinking about trees and the dimension of time.

What We Want Our Trees to Stand For

Over this past winter, it was announced that the tallest known tree in New York state, the white pine known as Tree 103, had died of natural causes and could no longer hold itself upright. It had been growing atop a hill in the Adirondacks since the mid-1600s. That is twice the lifespan of the oldest ash trees, even longer than most oaks have been around. Our Methuselah of the East was nevertheless a whippersnapper compared to the sequoia redwoods of the West, which (as everyone knows) live for thousands of years.

It was decided that the remains of Tree 103 would be left where they lie, to feed the soil where it once stood.

Trees have long been symbols of both transience and longevity, serving as images of the sacred as well as reminders of the sin of desecration. Back when I was a city dweller, long before I learned how to do a properly angled hinge cut, my wife and I would mark our calendars every year to attend the April cherry blossom festival at the Brooklyn Botanical Garden. We were joined by thousands of fellow spectators. The Brooklyn festival did not involve a Japanese tea ceremony, and the absence of hot dog stands expressed a collective desire to distinguish this occasion from a gathering at Coney Island.

The first recorded mention of Japan’s Springtime Sakura ritual appears in the oldest surviving text in Japanese literature, the Kojiki, completed in 712 CE. The annual tradition of gathering to view of the first cherry blossoms of the year has made popular a Japanese concept that pretty much everyone in the world can relate to, even if the Japanese word for it – mono no aware – is notoriously difficult to translate into English. Let’s review the options. Mono no aware has often been badly translated as “the sadness of things”; once very badly translated as “the ‘ahh-ness of things, life, and love”; and, at the end of the day, more or less decently translated as “the heightened awareness of impermanence.”

The most famous Japanese-style cherry blossom festival in the United States is probably the one in Washington D.C.. The annual tradition began in the early years of the 20th century, with a gift of cherry trees from Japan to the United States that was meant at the time to commemorate the beginning of a beautiful friendship between the two nations that was expected to last long into the new century. When the first batch of 2000 trees arrived from Japan in 1910, the Department of Agriculture discovered that they were infested with insects and had them promptly burned (the chestnut blight having been discovered only a few years earlier on Japanese chestnut trees brought over to the Bronx Zoo). The mayor of Tokyo decided to re-send the gift and upped the number to a pest-free batch of 3000 trees, which arrived in 1912 and have remained a major tourist attraction ever since.

People in the West, in Europe and in North America, have adopted somewhat different attitudes toward trees. On the one hand, there is the Japanese embrace of transience, mono no aware. Then there is the more typically Western attitude that has been characterized as a triumphalist monumentalism, tinged with a bit of guilt-driven desire to Build Back Better and atone for the loss and desecration of past monuments. Junichiro Tanazaki’s classic 1933 book In Praise of Shadows is an extended meditation upon these different world views, which are, to a surprising extent, reflected in our different attitudes toward trees.

Western cultures do have a peculiar guilt complex about trees that is not too hard to explain. A good deal of our bad conscience regarding trees comes from the cultural guilt we feel about having clear cut so much old growth in such a short amount of time. In the eastern United States, most of the reckless clear cutting had taken place by the middle of the 19th century. England had felled most of its old-growth trees by the mid-1600s, when the resident islanders began to realize that ships constructed of old-growth English oak rot much faster than oak trees can grow in the soils of England. The crisis prompted the English author John Evelyn to write his book Sylva, or A Discourse of Forest-Trees and the Propagation of Timber in His Majesty’s Dominions, as a somewhat belated plea for long-term woodlot management.

And more recently, there has been a lingering and vaguely post-colonial guilt over the role we have played in importing insects and fungi, like the chestnut blight fungus and the emerald ash borer and the spotted lantern fly. There is a painful irony in the fact that at the exact moment the white ash population in North America is being decimated by an insect, the ash trees in England and Europe are dying en masse due to the spread of a fungal disease.

Rebecca Solnit’s recent book Orwell’s Roses deals with these Western themes of guilt and atonement and trees as monuments. Solnit took her inspiration from a famously guilt-ridden Westerner, George Orwell, and an obscure essay he published in 1946 in which he reflected upon his visit to a small plot of land where, exactly ten years before, he had planted seven rose bushes, two gooseberries, and five fruit trees. With the exception of one dead fruit tree and one dead rose bush, Orwell discovered that all of what he had planted was still flourishing on its own a decade later.

The discovery was enough to set Orwell the essayist off on a discursive flight. His once-forgotten essay from 1946 offers a basic outline of the Western “monumentalist” view of tree planting as atonement:

The planting of a tree, especially one of the long-living hardwood trees, is a gift which you can make to posterity at almost no cost and with almost no trouble, and if the tree takes root it will far outlive the visible effect of any of your other actions, good or evil […] Even an apple tree is liable to live for about 100 years, so that the Cox [Cox’s Orange Pippin] I planted in 1936 may still be bearing fruit well into the 21st century. An oak or a beech may live for hundreds of years and be a pleasure to thousands or tens of thousands of people before it is finally sawn up into timber. I am not suggesting that one can discharge all one’s obligations towards society by means of a private re-afforestation scheme. Still, it might not be a bad idea, every time you commit an antisocial act, to make a note of it in your diary, and then, at the appropriate season, push an acorn into the ground.

When Rebecca Solnit, brimming with ideas for a new book, returned to the same site less than two decades into the 21st century, she discovered only a few of Orwell’s rose bushes were still living. There was no trace at all of the Cox’s Orange Pippin or any of the other long-lived hardwood trees.

“…Under Whose Shade We Do Not Expect to Sit”

The Japanese Sakura festival focuses attention on the spectacle of the transitory blossoms, poignant reminders that all things must pass. But what about the passing of the trees themselves? Some well-maintained Yoshino cherries can reach a ripe old age of 150 years. A wild black cherry can live up to 100 years or more. But they are the exceptions. The sweet and sour fruit-producing trees – like the Montmorency trees I planted last spring – will be well past its prime by the time your newborn baby finishes college.

Cherry trees in general are also highly susceptible to diseases. There are only a couple of dozen cherry trees that remain alive from the original batch of 3000 planted in D.C. in 1912, and even their survival is largely due to the rather lavish attention they receive (being pruned two or three times a year).

The 100-year-old or more apple trees that Orwell had in mind are ones grafted onto standard rootstock. The rootstock determines the vigor, size, and longevity of the tree (as well as other qualities, such as cold hardiness). Apples on standard stock (such as Antonovka) are much less popular today than they were in the 1930s; Fedco Trees is one of the only major nurseries that still sells trees on standard stock and advocates for that long-term option. More popular today are apples on dwarf and semi-dwarf stock, which are smaller in size and produce fruit earlier, but do not live nearly as long. A semi-dwarf tree on M111 stock will live maybe two to three decades, while a dwarf tree will live between one and two.

There is also a significant difference on the temporal scale between the long-lived fruit trees that Orwell had in mind and, say, a relatively short-lived peach tree. You can confidently plant a peach tree within the future shade of a standard apple tree, knowing that by the time the apple begins producing shade and fruit the peach tree will be long gone.

And if you decide to plant a Cox’s Orange Pippin, that most iconic of English heirloom apples, you should be prepared to deal with the slings and arrows of apple scab and the other life-shortening diseases to which the Cox’s Orange is notoriously vulnerable.

Embracing Ephemeral Trees

I am certainly planting trees on my property that I hope will last well into the 22nd century and beyond – various oaks, hickories, Northern Pecan, Hybrid chestnuts, Hazelnuts (which I have learned, to my surprise, can live more than 500 years). Not every tree is meant to outlive us, however. When thinking about the trees I want to plant in my regenerative project on my property, I must first consider the many trees I do not need to plant – the class of naturally vigorous trees that do not need care but do need taking care of. The trees I speak of would mostly be classified as invasive species. I prefer to call them ephemeral trees, and I must say that on the whole I welcome their presence.

Ephemeral Trees do not live long, are fast growing, and require that we live with them in a different way than we live with oak or hickory. We might even think of ephemeral trees as falling somewhere along the spectrum of annuals and perennials (in a manner of speaking). As a general rule, the fastest growing semi-invasive trees – and on my property that includes black locust (Robinia pseudoacacia), box elder (Acer negundo), and willow (varieties in the genus Salix) – are the ones that require managing and harvesting. Black locust and willow grow at an almost frightening speed, and locust is notorious for its suckering habit. One nice feature of locust and willow is that their leaves cast a dappled shade that allows other things to grow under their canopy (unlike, say, the broad-leafed and highly invasive Norway maple).

There are several uses for black locust and willow trees on the homestead. In the summertime, black locust growth – the leafed out suckers down low and leafy branches up high – provide excellent and nutritious food for goats. Locust, which is in the legume family, offers goats the same high levels of protein as alfalfa, and my goats consume it more eagerly than just about any other food on their menu. Willow branches are also excellent food for goats, with important medicinal properties to boot. If you do not have goats, then the trimmings from locust make a chop-and-drop mulch that is nitrogen rich.

Locust is an excellent fuelwood and is famously rot-resistant. Locust will season when left lying on the ground for long periods, whereas most other wood will begin to rot and degrade if not cut up and stacked right away. There is anecdotal evidence of locust fence posts that have been in the ground for more than half a century and show no signs of deterioration.

Ephemeral trees remind us that the largest and most mature-looking trees are not necessarily the oldest ones in the landscape. Willow trees put out on a lot of biomass within a very short time and can grow quite large.A locust tree can grow more than two feet a year, willows three to four feet.

Box elder can grow to huge proportions very rapidly. But as a low-density and rather soft hardwood, it is also weak structurally and easily blows down or collapses of its own weight (which is why they are not good trees to plant around your house). I must say that among my valued ephemeral trees, Box Elder is somewhat of an outlier in terms of practical use; it is not palatable fodder for animals, has negligible value as firewood, and rots quickly. It does, however, have a good deal of ecological value as hosts for birds and insects (including, of course, the ubiquitous box elder bug)!

Cycling and Sequestering Carbon at Home

One obvious use of trees is as a source of heat and energy. Trees long ago arrived at an elegant low-tech solution to the problem of long-term solar energy storage. The ash dieback in the eastern regions of North America has certainly produced a windfall of firewood. The surplus of dead and dying trees, all of it to be harvested on a tight schedule, has undermined the usual pleasures of scavenging and selecting fuelwood. Ash firewood improves with seasoning, even though it can be burned soon after harvesting. But like all firewood, ash will begin to degrade after a certain number of years even when kept under ideal conditions (well-ventilated and up off the ground). There is a lot of ash firewood now, to be sure. But I still think about where our firewood will come from ten or twenty years from now. Proper woodland management depends on a diversity of species, as well as differences in lifespans and time scales. In woodlot management, planning for the future means thinking in time scales of decades and quarter and half centuries.

The gold standard for high BTU’s is oak, a slow burning firewood that checks off just about all the boxes in terms of home heating needs (although oak requires 2-3 years of drying out and therefore a good deal of patience). The problem with oak is that it is slow growing and long-lived and provides ecosystem services that are unequalled by any other tree species. For many reasons, then, they are better left standing to live out their long lives. The same could be said about hickories, which do not even begin to produce hickory nuts until they have matured to about 40 years.

Are there any fast-growing, short-lived hardwoods that might substitute for oak and hickory? There are indeed. Above all, I am fascinated by black locust. It is intuitively tempting to see a straightforward correlation: to think that slow growing trees, like oaks and hickories, are energy dense fuelwood because it takes so long for them to grow and store away all that energy; whereas the fast growing trees grow fast, are not as dense, and store little energy. Fast-growing hardwoods like locust and mulberry disprove that hypothesis. Locust wood is very close to oak in terms of BTU’s but grows almost as fast as willow and box elder. Go figure.

Regardless of the wood I am burning, and in spite of the easy rationale for harvesting and controlling black locust, I do confess to feeling the need to do some sort of penance for the trees I have cut down and used for the short-term benefit warming myself. I find it helpful to think about burning fuelwood in the temporal context of carbon cycling. If you burn wood, then of course the stored carbon is emitted right away as it goes up in smoke. If you let wood rot on the ground, the process is slower. If you chop the wood and place it in the soil as mulch, the rate of release is somewhere in between (though mulch on the ground melts away much faster than one might expect).

It is also important to recognize that while fast-growing ephemeral trees sequester a lot of carbon in their biomass, that carbon is also cycled back much more quickly than carbon sequestered in slower-growing trees with longer lifespans. There is something of a tradeoff and a larger balancing out.

For the past several years, I have been sequestering small but significant amounts of carbon that will remain locked up and stable for much longer periods. The making of biochar – essentially high-quality, pure charcoal for use as a soil amendment – is a form of carbon sequestration that can be carried out at home. There are many ways to produce large amounts of biochar at a time: the so-called “trench method,” which is essentially a carefully monitored brush pile burn, and then there are various biochar retort designs made from 50-gallon metal drums, along with many other options you can readily find in a quick YouTube search.

All of these methods, however, require the burning of fuel in order to produce the heat for pyrolysis to occur. I am not comfortable with the idea of expending so much energy for this sole purpose, in effect emitting carbon to sequester some. Sean Dembrosky, who has a popular YouTube channel, turned me on to a simple and more multifunctional home-scale method for making biochar over the winter in the woodstove using a stainless-steel steam pan with a tight-fitting lid (the kind used in restaurants and hotels). You simply fill the steam pan with properly sized biomass, put on a semi-tight lid, and place the pan inside a burning woodstove that has reached at least 300 degrees F. As the biomass undergoes thermal decomposition and converts to biochar in the absence of oxygen, the volatile gases that escape from around the edges of the semi-tight lid are burned and produce a significant amount of additional heat (a relatively clean burn as well). This added heat saves additional fuelwood, and after a couple of hours you get a nice batch of good-quality biochar that you can incorporate in your soil in the Spring. And if the ancient terra preta biochar discovered in the Amazon Basin is any indication, the biochar you put in your soil will may remain there for over a millennium.

Asking Too Much of Trees

I have been speaking of carbon cycling and sequestering and offsetting at the scale of the small-property homestead. At that local scale, we can make complex stewardship decisions, monitoring the results and making adjustments and, in general, holding ourselves accountable. There may be mistakes and regrets and a learning curves, but in general we can see the impact we are having. We also have an intimate awareness of our resource dependence. As Aldo Leopold famously put it: “If one has cut, split, hauled and piled his own good oak, he will remember where the heat comes from.”

Far more problematic, from both an ecological and a logical point of view, are the recent claims that have been made for tree planting on a large scale as a means of atoning for our global disruption of the carbon cycle. As valuable as they are, trees have a very limited ability to serve as carbon sinks and simply cannot deal with the emitted amount of carbon we want them to sequester. Studies have shown that more than 80% of large-scale biodiversity offset sites have a high probability of failure.

Instead of pushing an acorn into the ground as symbolic atonement for our sins, the offset mentality is giving us a convenient rationale for continuing with business as usual, obscuring the fundamental difference between “net zero emissions” and the close-to-absolute zero emissions, the radical reduction in energy use, that is urgently required of a relatively small percentage of people in the so-called developed world.

To put it bluntly, the trees will not save our asses. And that is probably just as well. We already ask too much of them as it is, and for too long we have typecast them in symbolic roles within stories that have evolved far more recently than the evolutionary time span of the trees themselves. Trees, after all, have spent most of their time on Earth without swings attached to them.

An Early Spring

One of the most massive reforestation projects is currently underway near the Arctic Circle in Norway, where the tree line is rapidly advancing northward as the climate warms and the tundra thaws. The downy birch tree (Betula pubescens) is the most rapidly spreading pioneer species, thriving under the new conditions. As they take root, the birches create further warming in the soil and help accelerate the release of carbon and methane that have been sequestered since long before a human first planted a tree. No humans planted these trees, though in a sense we have. The birches are signs of an ecosystem seriously off balance, and it is hard not to infer that we have already passed an irreversible tipping point.

These Norwegian birches multiplying like rabbits are surely a poor substitute for the millennia-old sequoia redwoods lost in recent years to intense wildfires in California.

Meanwhile, the cherries have been blossoming much earlier than usual. Last year in Kyoto, they peaked on March 26, which is the earliest recorded date in 1,209 years. There are records that do go back that far. The Japanese were pioneers in what is now called phenology, or the careful recording of seasonal events, such as blossoming periods and bird migrations and last frost dates. The ancient Sakura tradition has provided a serendipitous wealth of recorded data for tracking climate change over the past several centuries.

The notion of carbon offsets and the related goal of net-zero emissions have been compared to the logic of medieval Catholic indulgences. I wonder, though, if a more apt analogy is with Kubler-Ross’s stages of grief, the third stage of which is bargaining. Acceptance is the fifth and final stage of Kubler-Ross’ stages of grief. And it seems that the Japanese, as a culture, were also pioneers in the sense of arriving at that stage long ago. As an embrace of transience and impermanence, the attitude of mono no aware is in many ways the opposite of despair.

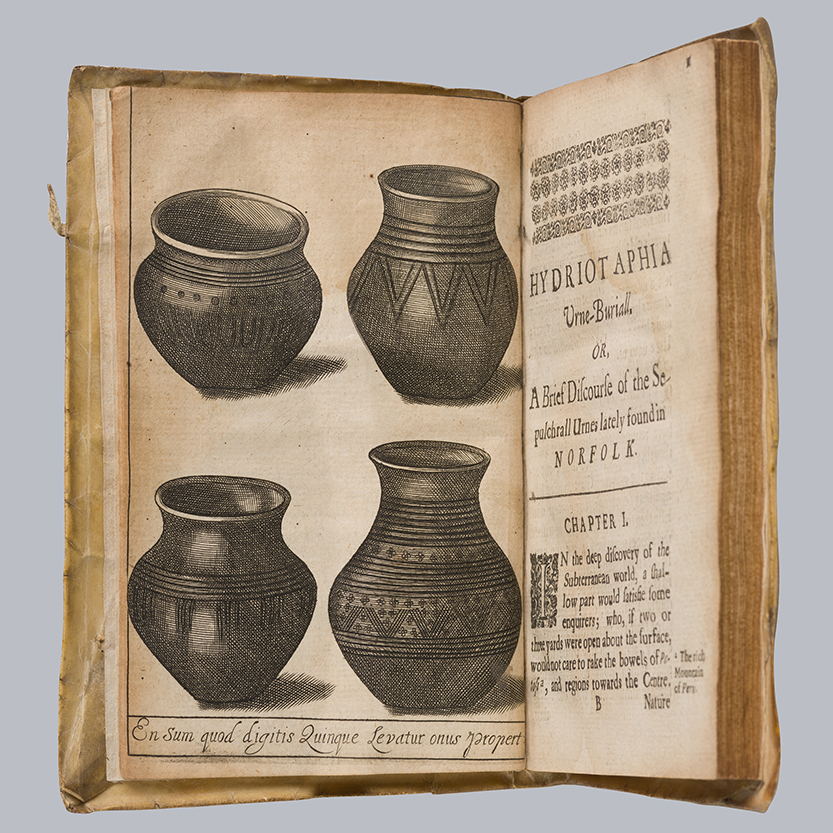

One of the most poetic meditations on mono no aware was actually penned by a Westerner, Sir Thomas Browne, whose 1658 essay Urn Burial was inspired by the unearthing of artifacts in an ancient Roman-era burial site in Norfolk, England. Browne was fascinated by the funerary practices of different cultures, and the essay contains long digressions on the ritual of cremation and, more generally, the uncanny process of combustion. The Urn Burial, incidentally, was written only a few years before John Evelyn wrote his manifesto on regenerative reforestation. It is hard to think of two contemporary writers more different from each other in temperament. Evelyn was a cheerful, pragmatic, reformer type (and a busy phenologist as well). Browne, by contrast, was the brooding type: someone we can easily imagine sitting up late by the fireplace transfixed by the embers and the coals, perhaps thinking about ancient oak trees, contemplating matter and memory and the essential unreality of both.

“If we begin to die when we live,” Browne wrote, “and long life be but a prolongation of death, our life is a sad composition; we live with death, and die not in a moment.”

This may sound at first like a morbid rumination. But the longer I live with this book and the closer I approach my own moment, the more I have come to see in these words the articulation of a healthy and life-affirming attitude. A life composed thus, lived according to this view, does not seem so sad to me. Simple sadness, moreover, fails to capture the meaning of mono no aware, just as it fails to describe the complex emotion that Browne was exploring.

Yes, the cherry blossoms will likely be coming early again this year as well, and it should come as no surprise if they bloom even earlier in the coming years. At least we can mark the occasion earlier and free up time for more activities. After drawing a good proper sigh, we can then rise up and get back out there to plant some more trees while we still can. Not every tree breaks dormancy at the same time. There is work to be done. In two or three decades, if all goes well, the trees we plant today might just have branches high enough for someone to hang a swing upon.

Derrick is a long-time and now periodic Owl Light contributor.