The Philanthropist – John Cushing Evans (1918-2008)

Richmond History

- By JOY LEWIS-

“Jack” Evans was born in Buffalo, the only child of John Evans and Grace Covey. He was of mature years when he wrote a detailed memoir of his family and his Hemlock boyhood called “Hemlock Memories.” In one piece he mentions that “near the end of World War I, Grandpa [Covey] took the engineer’s position at Hemlock…I was a few months old. My father was in the Army in Spartanburg, South Carolina. My mother and I came along with her parents.”

Photo courtesy of Joy Lewis

The living arrangement proved satisfactory and when Mr. Evans completed his military service he came home to his father-in-law’s house on Hemlock’s Main Street. Jack’s father was employed by the “railway mail branch of the postal service” and was away from home for long stretches of time. Young Jack became particularly close to his grandfather, reveling in tales of ole-timey railroading.

John Covey, born in the opening year of the Civil War, had grown up on a farm south of Buffalo. He was fascinated by the new-fangled railroad and determined to find his place in its organization. In his early twenties he was married to Emma VanSice, and in due time they became parents of three children: George, Ansel, and Grace. John was yet a young man when he’d earned the job of railroad engineer. For more than forty years he was master of the great steam locomotive – first on the Buffalo/Sayre, Pennsylvania, run on the Lehigh mainline, then from 1919 as engineer on the Rochester run out of Hemlock. All his days Jack remembered his grandfather at work, dressed “in his two-piece blue denim overalls, wearing heavy leather gloves with large stiff black cuffs, and his striped denim cap with the long visor.” In the cab his left hand “grasped the throttle, his right arm rested on the windowsill of the cab, ready at any instant to reach for the air valve to apply the brakes.”

The boy had a deep reverence for his grandfather’s locomotive, a respect shared by many passengers. At the end of every trip Engineer Covey would hurriedly disembark and commence faithfully to oil his engine. “Although he stood six feet in height he appeared tiny and obscure beside the locomotive. [Passengers as they passed by] always paused a moment to pay tribute to that behemoth of the rails, that magnificent iron horse…They admired the massive elegance of it all, the coal black locomotive with its contrasting nickel-plated whistle, bell, cylinder heads, and hand rails – a decorated black monster on wheels.” It was the thrill of Jack’s young life whenever he was allowed to ride the rails with his Grandpa.

Jack wrote extensively of his Hemlock boyhood. He had detailed memories of delivering the Times-Union newspaper at age eleven, attending the Little World’s Fair every autumn, feeding and milking Dr. Trott’s cow which was kept in the Coveys’ barn in exchange for some of the milk. He and his friend Bruce Wemett once climbed the abandoned water tower on Railroad Avenue, which was full of pigeons and danger. They fashioned a homemade rowboat and took her sailing on the mill pond. “One drizzly Saturday in April I caught seventeen catfish in that tub while floating beneath the umbrella,” he remembered.

He and his friends swam in the creek on Adams Road, jumping off the railroad trestle into the murky water below. With Bruce and other boys, he “ice skated [on the mill pond] in winter, boated and fished in summer.” The dam which formed the pond provided a canny boy with “a clandestine route into the fairgrounds, thereby avoiding paying the admission charge.”

Vividly Jack remembered the first barnstormer to fly into Hemlock Airport in his WWI biplane, a Jenny. The year was 1929 and Jack was ten years old. Children and adults alike flocked up the hill to see the plane, a two-seater with an open cockpit, a wooden fabric-covered frame painted with a colorful American flag, a six-cylinder engine, and a two-blade propeller. The sight of that plane and the daring pilot outfitted in his “brown leather flight jacket and leather helmet with goggles” was one Jack never forgot.

1930 brought deep sorrow to the Covey and Evans families. Jack was twelve years old in the fall of that year when his beloved Grandfather Covey died after a four-day siege of “intestinal grippe.” His obituary gave the details of his life and family, but it is Jack’s eulogy that bears witness to his grandfather’s lifework:

“The period in which Grandpa grew and prospered corresponded with the crescendo of the American railroads. The railroad did not offer me the lifelong opportunity that it did to Grandpa, but the railroad, with its many attendant experiences, did offer me an exciting, enlightening and happy beginning. I learned many things from the railroad – about machines and personalities and their meshing together, about attention to duty and punctuality. I reveled in the pastimes it provided – walking the track, riding the rails, diving off the trestle, fishing in the pond and exploring the railroad property. Ah! The railroad, what memories…”.

Less than two weeks after Mr. Covey died the family endured another blow when on September 23, his widow succumbed to pneumonia. Jack’s Uncle George, his mother’s brother, died later that same day. Not surprisingly, Jack wrote little of this heartbreaking time.

He and his parents continued to live in Hemlock until Jack graduated from Hemlock High School; he was valedictorian of the class of 1935. He went on to graduate from the University of Rochester, class of 1939, with a Bachelor of Science degree. He married Madlyn Horacek and fathered five children. His employment history included some years at Kodak and a stint as professor at the U of R Institute of Optics before founding his own optics-producing company in 1967, Velmex.

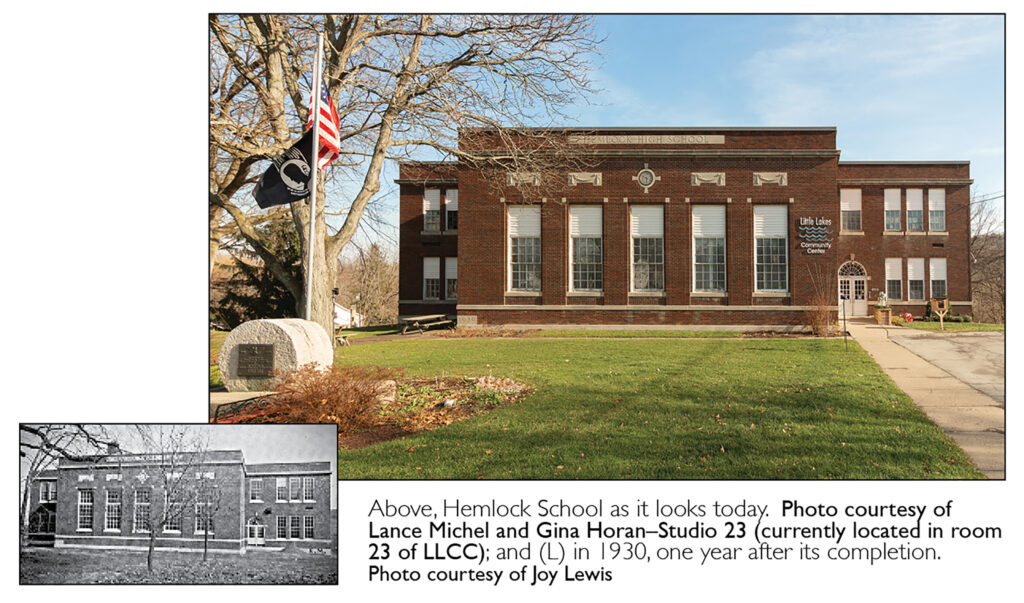

In 1983 Velmex purchased the empty Hemlock School building on Main Street where Jack had long-ago attended. At first thought, Jack considered whether the building might be used for manufacturing, but that venture never came to be. After upgrading the five-decades-old building with a new heating system, windows, and doors, the Jack Evans Community Center was created. In 1996 the building was donated to the town of Livonia.

As maintenance costs escalated the town, in the fall of 2016, decided to close the building. Two score local residents lamented that decision and over the course of eighteen months the building was purchased, refurbished, and rechristened the Little Lakes Community Center. Today the building houses several enterprises, including an artist’s studio, a photographer, a yoga instructor, a dance studio, a community meeting room and catering kitchen, and a local history room.

Jack Evans’ legacy and vision lives on. He had a generous affection for his hometown and the scenes of his youth. His death on September 20, 2008, was mourned by many. His obituary noted that “Jack’s philanthropic interest included sponsorship of engineering students at the University of Rochester; donations to the town of Richmond recreational facilities adjacent to Sandy Bottom Beach; and local community sports teams.”