The Monthly Read: A Lucky Man review

by Mary Drake – The Inner Life of Men

The Inner Life of Men

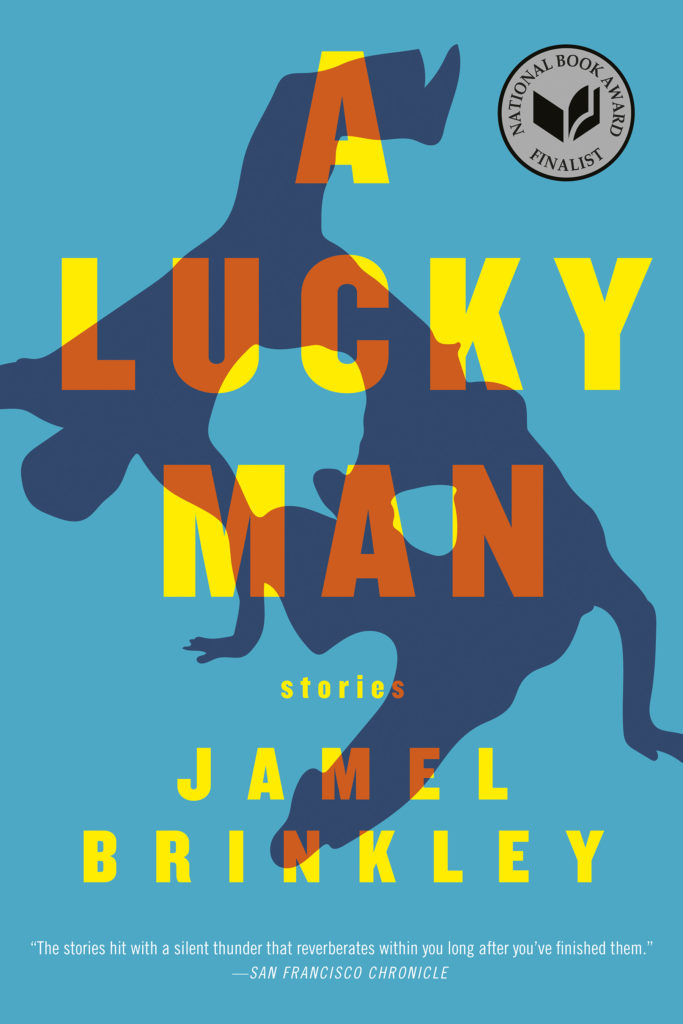

~ A review of A Lucky Man by Jamal Brinkley

Some say the literary novel is dead. If this is true, perhaps the short story has taken its place. More and more anthologies of quality short stories seem to be turning up. I reviewed one such anthology last month, and here I am writing about another, although I didn’t come to this anthology on my own. I discovered it when I accompanied my daughter one evening to hear an author speak at her college. That author was Jamel Brinkley and the title of his book is A Lucky Man.

Brinkley could be the subject of his own book because he is indeed lucky. This, his first book, has been called a “stunning debut” and has garnered him much attention and critical acclaim. He is a soft spoken man, but as soon as he began reading some excerpts from the stories, I recognized his sensitive insight into human nature and his quiet control of language. He is a black man whose stories concern the lives, hopes, and challenges of black males, from those as young as eight through middle age. It says something about these stories that, although I am neither black nor male, they held my attention and left me turning them over in my thoughts afterwards. The collection is not only thought provoking but also educational.

I learned about capoeira, a type of martial art that combines acrobatics, dance and music that originated among sixteenth-century African slaves in Brazil. Brinkley uses it in the story “Everything the Mouth Eats” as a metaphor for what is going on between two estranged brothers who are fighting and dancing around their relationship and their troubled past. The narrator Eric says in the beginning, “I hadn’t had a talk—a real talk—with my brother in many years. Maybe we’d never had one. In any case, I wasn’t sure either of us even knew how.”

The story alternates between the two brothers’ road trip to a capoeira convention and remembrances of their childhood together. They are half-brothers and their father, Carlos’s biological father and Eric’s stepfather, has sexually abused both of them. They are five years apart in age, and as children were often left alone. One day while roughhousing, the narrator holds Carlos in a head lock and unintentionally causes him to lose consciousness. Eric fears the worst, but when Carlos regains consciousness, the little boy is convinced in the irrational way of children that his older brother has somehow saved him. After that, Eric tells us that Carlos “built a little religion and installed me as its godhead.” But because as children they were initiated too soon into the world of sex and violence, it is no wonder that as adults they are confused about how to relate to one another. Their mother has told Eric, who is older, to look out for his younger brother, but at his first opportunity, Eric left home and lost track of what happened to Carlos. Now, as adults, they are trying to reconnect but are having trouble overcoming their past and who was responsible for what. Carlos, we’re told, had sunk so far as to become homeless, and has only rebounded because of his “ ‘blessings,’ which he said had saved his life.” They are his wife, his baby daughter, and capoeira. It’s more than a sport, it’s a way of developing a family, of expressing anger within strict bounds. It provides relief as well as bonding, and capoeira feeds you all you could want; it is everything the mouth eats.

While reading Brinkley’s short stories I also learned about J’ouvert, a type of parade/street party that originated in Caribbean countries like Trinidad and the Dominican Republic. The celebration also takes place in areas with large Caribbean immigrant populations, such as Brooklyn. I was reminded of Mardi Gras, but J’ouvert takes place on what in America is Labor Day, and it involves calypso music and dancing in the streets. In his story by that title, Brinkley tells about a poor seventeen-year-old boy, Ty, turned out of his home for the day while his mother entertains a boyfriend and he babysits his differently-abled younger brother. All Ty wants to do is alleviate his boredom and prove he’s a man by going to the West Indian Day Parade by himself. It reminds him of when he went with his father who has disappeared. But Ty soon discovers that there is even more fun to be had at J’ouvert, which roughly translates from French to mean “when day opens.” The street party begins before dawn and Ty gets swept up into it. Someone shouts at him,“Dance or go home!” And so he does.“I was grabbed by it, pulled into it, twisted up in the songs and yells and laughter.” Ty is having such a good time that he forgets about his family’s poverty, his father’s abandonment, and his challenges coming into manhood, but he also forgets about his little brother until he sees him being carried off in the crowd. Everything becomes less important at that moment than recovering his little brother. Ty realizes what it means for someone to depend on you.

The title story of the book A Lucky Man is about the middle-aged Lincoln Murray, a security guard for the last sixteen years at Tilden School, which the reader is told is “the “second oldest private school in the entire country.” However, “the security and maintenance staffs, ‘the invisible folks,’ . . .seemed to be the only black and brown people in the school.” But Lincoln is married to the beautiful Alexis who has a professional job in a museum; his security guard co-worker James tells him, “You’re a lucky man. I wish I could get me a high-quality woman like that. A good woman.” Only Alexis has left Lincoln. He wonders what has become of his life. When he met and married Alexis, twenty-two years earlier, “they were equals. He was as handsome as she was beautiful and bright, and despite their age difference he had as much to expect from the coming years as she did.” Only life hasn’t turned out as he had expected. Now he wonders if his wife’s friends ever tell her that she is lucky to have him. Unlikely, since he has failed in his ambition to become a professional boxer and has failed in his marriage. Then his boss sends him home for some R and R, telling him “We’ll be fine without you.” But Lincoln’s work is the only thing he’s got going for him. Well. . .not the only thing. Lincoln has developed the habit of secretly taking pictures of attractive women he comes in contact with during the day—on the bus or in the subway station. In private moments he looks at the pictures and fantasizes. Only, Alexis has discovered the pictures. Then, on his way home from work, a random woman on the sidewalk accuses Lincoln of taking pictures of young girls coming out of a local school. It doesn’t matter that he vigorously denies it, that he was actually texting; she calls him a “creep” and a “pervert.” He may not have done what she accused him of, but he knows that he is guilty. With reluctance, he deletes the pictures he has taken. After they are all gone, “he realized with some surprise that he hadn’t taken any other pictures, not even a single one of his wife.” How could he have missed such luck?

Brinkley’s stories about boys, teenagers, and men all have a ring of truth. They don’t shy away from feelings and problems that are difficult to express and which perhaps have no resolution. Like life, his stories have no real endings. When I heard him speak, Brinkley said he doesn’t want to spoon feed readers and make his stories too easy. They’re not. But like the best stories, they draw you in yet provide no facile answers, just leave you thinking.