A Little help from hoop houses

by Mary Drake –Before moving to New York State, my husband and I had a small farmette in Lancaster County, Pennsylvania. Since we had eight acres and we both liked to garden and to eat locally, we planted two large vegetable gardens as well as fruit trees. We milked a cow and raised our own beef cows and pigs.

We drank our milk fresh everyday, even though neighbors warned us that we would “end up in the hospital,” although we never did. I called the milk “fresh” rather than “raw” because I thought calling it raw sounded unsavory, but my daughter began referring to store-bought milk as “cooked.” We all agreed that the flavor had been cooked out of it. She said it tasted burned. Instead, each morning after milking we would drink the milk from the previous day which had gotten cold in the refrigerator. We would shake the container to redistribute the cream that had collected on top back into the milk.

We felt ourselves to be part of a back-to-nature movement, and that’s why we joined PASA, the Pennsylvania Association for Sustainable Agriculture. I must admit that when we first joined, and perhaps for a while afterwards, I only had only the fuzziest of notions what it meant for agriculture to be sustainable. Did that mean the vegetables we grew would sustain us? Perhaps it meant we wanted to sustain the produce we grew, make it last longer into each season?

What it meant, I later learned, was growing food in ways that the Earth could support year after year, that wouldn’t hurt the present or future generations by overtaxing the soil or damaging the environment.

As part of our PASA membership, we were entitled to go on their field days, the first of which was held at Penn State to see something called “hoop houses.” I was unsure what to expect or why we were even going, but it sounded like a fun day trip.

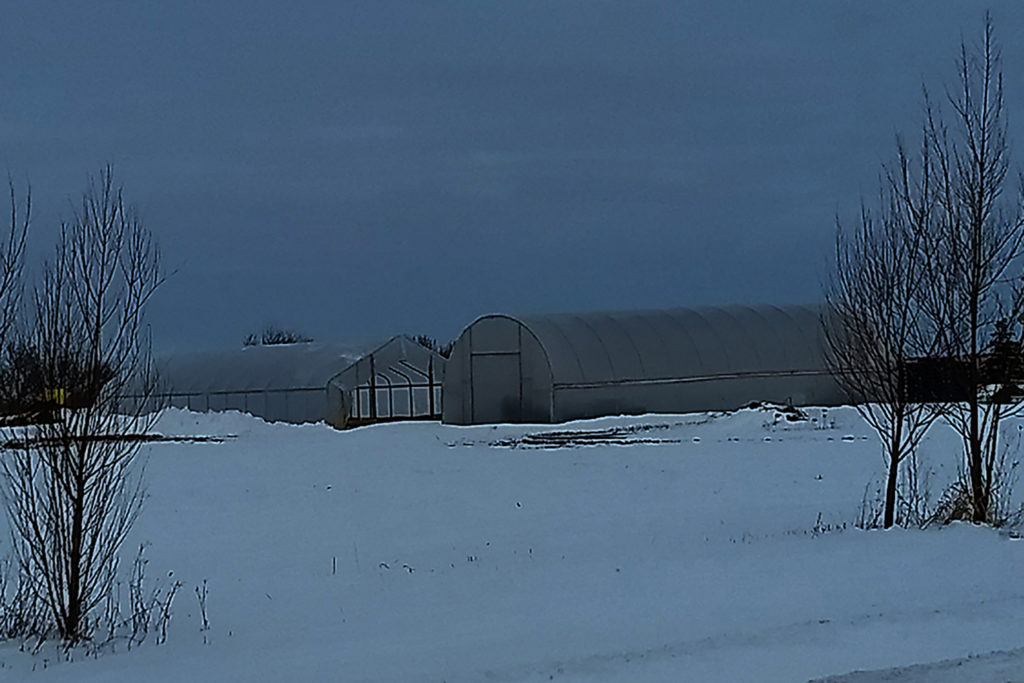

What we saw when we got there were structures resembling greenhouses. Why did they call them “hoop” houses, I wondered. The name made me think of something round, like hula hoops. But hoop houses, although they look a lot like greenhouses, are different in some important ways. First of all, instead of being made of glass, or more recently acrylic, they are made of semi-circular metal rings (a half a hoop) over which is laid opaque heavy-duty plastic. The construction makes hoop houses moveable, unlike greenhouses.

The second major difference is that hoop houses are more energy efficient. Greenhouses are climate controlled with heaters to use when temperatures dip down and ventilation systems to prevent them from overheating. Hoop houses, however, rely solely on the warmth of the sun. This makes them slightly less useful than greenhouses, especially in the winter, but they don’t require any kind of fuel other than solar energy, and they still extend the growing season. To prevent hoop houses from getting too warm in the summer, they are ventilated by rolling up the lower portion of the plastic to allow airflow.

And did I mention they are much less expensive to build than a greenhouse?

But like greenhouses, hoop houses make it easier to grow certain plants. It’s easier to prevent disease and insect damage inside a hoop house. Some fruits and vegetables,for instance raspberries and tomatoes, are highly susceptible to disease if they receive too much water. When I first

saw the experimental hoop houses at Penn

State, one of them had been used to grow red raspberries, and I was astounded to see the size and quantity of the berries. Since red raspberries are one of my favorite fruits but are challenging to grow outdoors because they are susceptible to grey mold and powdery mildew, I was immediately a fan of hoop houses.

When we moved to New York State and started vegetable gardening up here, my husband immediately began to have trouble growing tomatoes. Aside from nutrient deficiencies in the soil (I blamed the glacier for moving our topsoil elsewhere), we also battled too little sun, a shorter growing season, cooler temperatures at night, and sometimes too much rain. If tomatoes get too much moisture not only does the tomato split and loose some of its flavor, but the plants themselves are subject to mildews and fungal diseases, such as early and late blight, which might mean fewer or no tomatoes are produced. Hoop houses solve much of this because the amount of moisture the plants receive can be controlled. We finally stopped trying to grow our own tomatoes and now buy them from a neighbor—who has a hoop house.

There are many fruits and vegetables that grow just fine in New York’s climate—cabbage, broccoli, cauliflower, potatoes, and apples, for example, but hoop houses can make gardening easier, especially if you’re trying to grow finicky plants, and they can keep out some of the critters that also like to make meals out of what we are planning to eat.